Native Land

The agrarian way of life of the Lenape Indians was forever changed when Hudson’s Half Moon sailed into the Valley

Was it a floating house? A great fish? Were the people on board spiritual beings or messengers from the creator? When local natives first saw Henry Hudson’s Half Moon sail by, they probably didn’t guess that its appearance signaled the beginning of the end of their way of life. The conference “Before Hudson: 8,000 Years of Native American History and Culture,” which is being hosted by Historic Huguenot Street on May 1-2 in New Paltz, takes a look at these pre-colonial glory days.

Hudson’s original mission, of course, was to find a passage to the Orient. Unknowingly, when he sailed up his namesake river, he encountered people whose ancestors had relocated from Asia thousands of years before. Today they are known by several names and often collectively called Delaware or Lenape (Len-AH-PAY, which means “common person” or “human being”) Indians. These tribes lived in loosely confederated but autonomous villages which stretched from the Hudson Valley south to Manhattan and Long Island, into western portions of Connecticut, across New Jersey, and into parts of Pennsylvania and Delaware. They went by the names of their villages. “Esopus,” for example, comes from a word meaning “stream” or “brook” and refers to a group that lived in the environs of the Esopus River in Ulster County.

|

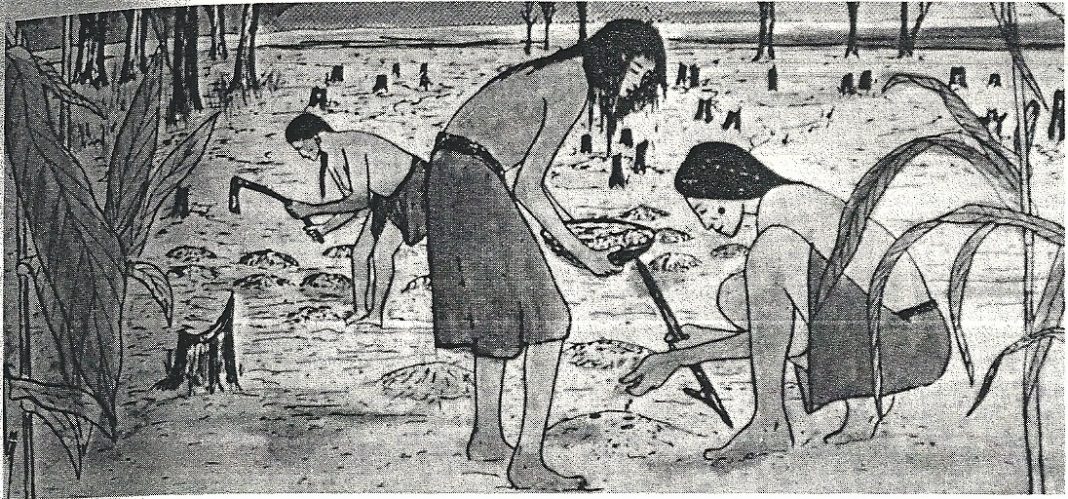

“I don’t want to say that they never got into skirmishes, but they did seem to have had a fairly peaceful existence and would intermarry and trade,” says conference speaker Dr. David Oestreicher, author of Lenape: The First Inhabitants (SUNY Press) and curator of an Ellis Island exhibit on the tribe which runs through January 2010. “Basically, there was sexual division of labor. Women did the gardening; they grew squash, beans, pumpkins, tobacco, and gathered wild plant foods. Men would hunt and fish. The Europeans were perplexed by that. The explorers described how the women were stuck with all the chores and that the men were lazy. Back in Europe, farming was man’s work and more large scale. Hunting was more for nobility.”

When Dutch settlers, followed by the English and others, began arriving in the Valley soon after Hudson’s journey, they gravitated to the same spots as the natives, who had already picked prime locations for their base camps. On Huguenot Street, archeological digs near the stone houses built by French settlers in the late 17th century have turned up native storage pits for corn and beans as well as “some really large hearths with bear remains,” says Dr. Joe Diamond, a professor of anthropology at SUNY New Paltz who will speak at the conference. “From about 7,000 B.C., people were probably visiting the site during the spring and fall to get off the flood plain and move the crops so they didn’t get washed away. It’s called ‘centrally based wandering,’ moving your base camp to another location when resources become available. So in spring they might have headed for the river to fish, and in fall they’d look for walnuts, acorns, and chestnuts.”

A touching find from the excavations — and one that will be on display at the conference — was a dog burial dating from around 1300. “It was done by somebody who really loved their old dog,” says Diamond. “The dog was arthritic and had dental problems, but was carefully laid out in a pit.” Esopus gravesites have also been identified, though not excavated, on Huguenot Street. “They also practiced secondary burial,” says Diamond. “If someone died in a base camp in one location, you might go back several months later, open the grave, ritually clean up the bones and wrap them in fresh deer or bear skin to take back and bury with the family in another place.”

|

Sadly, the number of burials spiked after the Europeans arrived. By the 1630s smallpox ravaged the natives, the first of many epidemics to which the tribes had no immunity.

News of abundant beavers in the Hudson Valley led to more incoming ships and the establishment of a fur trade. The natives traded pelts for coveted European goods like metal and cloth. Tribes fought with each over trading rights with the Dutch (and later the English), and competition arose over trapping territories. “It was hard to keep their ways,” says Oestreicher. “It was difficult not to be a part of the trade. The different colonists made alliances with Indians and armed them with guns in exchange for furs. To survive you needed to be part of this trade.”

In 1643 a group of Mohawks (who lived to the north), in allegiance with the Dutch, attacked a group of Wappinger Indians. The Wappinger then fled south and were massacred by the Dutch. All hell broke loose after that. The Lenape tribes banded together in what became an ongoing war with the Dutch, both sides raiding each other and taking hostages. Conflict with the Esopus led to the Dutch building a stockade in Kingston. Tribes also built fortresses in self-defense: Diamond’s next archeological dig on Huguenot Street, slated for this summer, will investigate remains of a native stockade.

As the Europeans encroached on their land and competed with them for natural resources, the tribes began to get squeezed out. By 1700, the native population was a fraction of its original size. Pressure to sell land was intense. The Lenape tribes began to retreat to more remote areas, eventually making their way to settlements in Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Ontario.

It was at one such settlement in Oklahoma that Oestreicher began his research in the 1970s and met Touching Leaves Woman, one of the very few remaining speakers of the Lenape language. Incredibly, she related tales — passed down through generations of ancestors — of events which took place at the time of Hudson’s arrival in the New World. She even recounted the story of her people boarding the Half Moon and trying alcohol for the first time. Readers of this column might recall that this incident is also fully recounted in the journal of the ship’s first mate, Robert Juet. “These were stories handed down that the native people never forgot, they made such an impact,” says Oestreicher. “Touching Leaves Woman told me that when she would come back east to visit, she would hear the voices of the ancestors, glad she had returned. It would give her chills. Just to hear about it still gives me chills, too.”

Before Hudson: 8,000 Years of Native American History and Culture

May 1-2 at Historic Huguenot Street

18 Broadhead Ave., New Paltz

845-255-1660; www.huguenotstreet.org or www.ucqc.org