Many people believe that America is named after Amerigo Vespucci. While others hold fast to the idea that the continent was named after the indigenous people of this land. My contention is that this is only part truth. The name America does come from the Ancient indigenous People of Peru, but it was a name applied to that territory and that territory alone. The people outside of that territory had their own unique name for the lands they occupied. Furthermore the naming of entire continents is strictly a European concept and done so to place ownership on entire landmasses. Our respective ancestors were not concerned with that.

Although the religion practiced surrounding the Plumed Serpent can be found all over the continent, that specific dialect can not. So calling all of the continents, north, south and central by any one name is misleading and creates a hierarchy in indigenous cultures that did not exist prior to the arrivals of Europeans.

Now lets look at the mythology/history that gave us the title America.

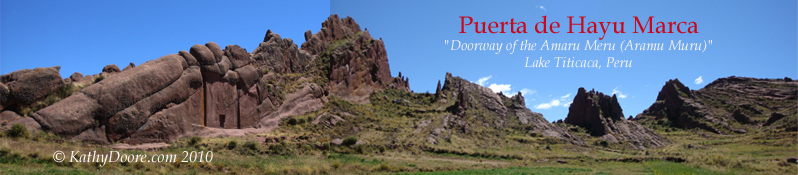

In mythology of Andean civilizations of South America, the amaro, amaru(quechua) or katari (aymara) is a mythical serpent or dragon, most associated with the Tiwanaku and Inca empires. In Inca mythology, the amaru is a huge double-headed serpent that dwells underground. Illustrated with the heads of a bird and pumas, amarus can be seen emerging from a central element in the center of a stepped mountain or pyramid motif in the Gateway of the Sun at Tiwanaku, Bolivia. When illustrated on religious vessels, the amaru is often seen with bird-like feet and wings, so that it resembles a dragon. The amaru was believed capable of transgressing boundaries to and from the spiritual realm of the subterranean world.

WHO ARE THE QUECHUA or KATARI(AYMARA) PEOPLE?

-

1.a member of an American Indian people of Peru and parts of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador.

-

2.the language or group of languages of the Quechua.

-

1.relating to the Quechua people or their language.

PRONUNCIATION:eye-MAHR-ah

LOCATION:Bolivia; Peru; Chile

POPULATION:About 2 million (Bolivia); 500,000 (Peru); 20,000 (Chile)

LANGUAGE:Aymara; Spanish

RELIGION:Roman Catholicism combined with indigenous beliefs; Seventh Day Adventist

1 • INTRODUCTION

The Aymara are the indigenous (native) people who live in thealtiplano(high plains) of the AndesMountains of Bolivia. Bolivia has the highest proportion of indigenous peoples of any country in South America. It is also the poorest country on the continent.

Bolivia was colonized by Spain. The Aymara faced great hardships under Spanish colonial rule. In 1570, the Spanish decreed that the natives would be forced to work in the rich silver mines on the altiplano. The city of Potosí was once the site of the richest silver mine in the world. Millions of Aymara laborers perished in the wretched conditions in the mines.

2 • LOCATION

The Aymara live on high-altitude plains in the Bolivian Andes, on the Lake Titicaca plateau near the border with Peru. The altiplano is at an elevation of 10,000 to 12,000 feet (3,000 to 3,700 meters) above sea level. Weather conditions are cold and harsh, and agriculture is difficult.

An ethnic group closely related to the Aymara lives among the Uru islands on Lake Titicaca. These communities live not on land but on islands that are made of floating reeds.

An estimated two million Aymara live in Bolivia, with five hundred thousand residing in Peru, and about twenty thousand in Chile. The Aymara are not confined to a defined territory (or reservation) in the Andes. Many live in the cities and participate fully in Western culture.

3 • LANGUAGE

The Aymara language, originally calledjaqi aru(the language of the people), is still the major language in the Bolivian Andes and in southeastern Peru. In the rural areas, one finds that the Aymara language is predominant. In the cities and towns the Aymara are bilingual, speaking both Spanish and Aymara. Some are even trilingual—in Spanish, Aymara, and Quechua—in regions where the Incas predominate.

4 • FOLKLORE

Aymara mythologyhas many legends about the origin of things, such as the wind, hail, mountains, and lakes. The Aymara share with other ethnic groups some of the Andean myths of origin. In one of them, the god Tunupa is a creator of the universe. He is also the one that taught the people customs: farming, songs, weaving, the language each group had to speak, and the rules for a moral life.

5 • RELIGION

The Aymara believe in the power of spirits that live in mountains, in the sky, or in natural forces such as lightning. The strongest and most sacred of their deities is Pachamama, the Earth Goddess. She has the power to make the soil fertile and ensure a good crop.

Catholicism was introduced during the colonial period and was adopted by the Aymara, who attend Mass, celebrate baptisms, and follow the Catholic calendar of Christian events. But the content of their many religious festivals shows evidence of their traditional beliefs. For example, the Aymara make offerings to Mother Earth, in order to assure a good harvest or cure illnesses.

Read more: http://www.everyculture.com/wc/Afghanistan-to-Bosnia-Herzegovina/Aymara.html#ixzz4xUSaTDTd

-

1A member of a South American people inhabiting the high plateau region of Bolivia and Peru near Lake Titicaca.

- ‘Many Aymaras reside in cities and live in modern houses or apartments.’

- ‘The concern in Bolivia is that if the state is left to its own devices, with a strong but fragmented opposition movement, it will use its collective strength to smash movements such as that of the Aymara.’

- ‘Our church is in a companion relationship with the Bolivian Evangelical Lutheran Church, most of whose 20,000 members are Aymara.’

- ‘For more than 500 years we, the Quechuas, Aymaras and Guaranis, the Indians who are native to this noble land, have been subject to slavery.’

- ‘Well, he must have had a straw boat like the Aymaras use in Lake Titticacca.’

-

2mass noun The language of the Aymara, with over 2 million speakers. It may be related to Quechua.

- ‘More than 50 percent are Amerindians who speak mainly Quechua or Aymara as well as Spanish.’

- ‘Native American communities still maintain their indigenous languages such as Quechua, Aymara, and the lesser known Indian languages spoken by the Amazon groups.’

- ‘Several varieties of Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara are spoken, and all have influenced one another in vocabulary, phonology, syntax, and grammar.’

- ‘Lots of them don’t speak Spanish, and I don’t know Quechua or Aymara.’

- ‘Furthermore, the local radio stations often broadcast programs in local languages, e.g. Quechua and Aymara, in addition to programs in the national language, i.e. Spanish.’

Tiwanaku Empire – Ancient City and Imperial State in South America

Capital City of an Empire Built 13,000 Feet Above Sea Level

/monolith-ponce-viewed-through-the-massive-door-of-kalasasaya-from-the-semi-subterranean-temple-tiwanaku-bolivia-637216384-58c149a73df78c353ccf7a16.jpg)

Monolith Ponce viewed through the massive door of Kalasasaya from the Semi-Subterranean Temple, Tiwanaku, Bolivia. florentina georgescu photography / Getty Images The Tiwanaku Empire (also spelled Tiahuanaco or Tihuanacu) was one of the first imperial states in South America, dominating portions of what is now southern Peru, northern Chile, and eastern Bolivia for approximately four hundred years (AD 550-950). The capital city, also called Tiwanaku, was located on the southern shores of Lake Titicaca, on the border between Bolivia and Peru.

TIWANAKU BASIN CHRONOLOGY

The city of Tiwanaku emerged as a major ritual-political center in the southeastern Lake Titicaca Basin as early as the Late Formative/Early Intermediate period (100 BC-AD 500), and expanded greatly in extent and monumentality during the later part of the period.

After 500 AD, Tiwanaku was transformed into an expansive urban center, with far-flung colonies of its own.

- Tiwanaku I (Qalasasaya), 250 BC-AD 300, Late Formative

- Tiwanaku III (Qeya), AD 300-475

- Tiwanaku IV (Tiwanaku Period), AD 400-800, Andean Middle Horizon

- Tiwanaku V, AD 800-1150

- hiatus

- Inca Empire, AD 1400-1532

TIWANAKU CITY

The capital city of Tiwanaku lies in the high river basins of the Tiwanaku and Katari rivers, at altitudes between 3,800 and 4,200 meters (12,500-13,880 feet) above sea level. Despite its location at such a high altitude, and with frequent frosts and thin soils, perhaps as many as 20,000 people lived in the city at its heyday.

During the Late Formative period, the Tiwanaku Empire was in direct competition with the Huari empire, located in central Peru. Tiwanaku style artifacts and architecture have been discovered throughout the central Andes, a circumstance that has been attributed to imperial expansion, dispersed colonies, trading networks, a spread of ideas or a combination of all these forces.

CROPS AND FARMING

The basin floors where Tiwanaku city was built were marshy and flooded seasonally because of snow melt from the Quelcceya ice cap. The Tiwanaku farmers used this to their advantage, constructing elevated sod platforms or raised fields on which to grow their crops, separated by canals.

These raised agricultural field systems stretched the capacity of the high plains to allow for protection of crops through frost and drought periods. Large aqueducts were also constructed at satellite cities such as Lukurmata and Pajchiri.

Because of the high elevation, crops grown by the Tiwanaku were limited to frost-resistant plants such as potatoes and quinoa. Llama caravans brought maize and other trade goods up from lower elevations. The Tiwanaku had large herds of domesticated alpaca and llama and hunted wild guanaco and vicuña.

STONE WORK

Stone was of primary importance to Tiwanaku identity: although the attribution is not certain, the city may have been called Taypikala (“Central Stone”) by its residents. The city is characterized by elaborate, impeccably carved and shaped stonework in its buildings, which are a striking blend of yellow-red-brown locally-available in its buildings, which are a striking blend of yellow-red-brown locally-available sandstone, and greenish-bluish volcanic andesite from farther away. Recently, Janusek and colleagues have argued that the variation is tied to a political shift at Tiwanaku.

The earliest buildings, constructed during the Late Formative period, were principally built of sandstone.

Yellowish to reddish brown sandstones were used in architectural revetments, paved floors, terrace foundations, subterranean canals, and a host of other structural features. Most of the monumental stelae, which depict personified ancestral deities and animate natural forces, are also made of sandstone. Recent studies have identified the location of the quarries in the foothills of the Kimsachata mountains, southeast of the city.

The introduction of bluish to greenish gray andesite happens at the start of the Tiwanaku period (AD 500-1100), at the same time as Tiwanaku began to expand its power regionally. Stoneworkers and masons began to incorporate the heavier volcanic rock from more distant ancient volcanoes and igneous outgroups, recently identified at mounts Ccapia and Copacabana in Peru.

The new stone was denser and harder, and the stonemasons used it to build on a larger scale than before, including large pedestals and trilithic portals. In addition, the workers replaced some sandstone elements in the older buildings with new andesite elements.

MONOLITHIC STELAE

Present at Tiwanaku city and other Late Formative centers are stelae, stone statues of personages. The earliest are made of reddish-brown sandstone. Each of these early ones depicts a single anthropomorphic individual, wearing distinctive facial ornaments or painting. The person’s arms are folded across his or her chest, with one hand sometimes placed over the other.

Beneath the eyes are lightning bolts; and the personages are wearing minimal clothing, consisting of a sash, skirt, and headgear. The early monoliths are decorated with sinuous living creatures such as felines and catfish, often rendered symmetrically and in pairs. Scholars suggest that these might represent images of a mummified ancestor.

Later, about 500 AD, the stelae change in style. These later stelae are carved from andesite, and the persons depicted have impassive faces and wear elaborately woven tunics, sashes, and headgear of elites. The people in these carvings have three-dimensional shoulders, head, arms, legs, and feet. They often hold equipment associated with the use of hallucinogens: a kero vase full of fermented chicha and a snuff tablet for hallucinogenic resins. There is more variations of dress and body decoration among the later stelae, including face markings and hair tresses, which may represent individual rulers or dynastic family heads; or different landscape features and their associated deities. Scholars believe these represent living ancestral “hosts” rather than mummies.

TRADE AND EXCHANGE

After about 500 AD, there is clear evidence that Tiwanaku established a pan-regional system of multi-community ceremonial centers in Peru and Chile. The centers had terraced platforms, sunken courts and a set of religious paraphernalia in what is called Yayamama style.

The system was connected back to Tiwanaku by trading caravans of llamas, trading goods such as maize, coca, chili peppers, plumage from tropical birds, hallucinogens, and hardwoods.

The diasporic colonies endured for hundreds of years, originally established by a few Tiwanaku individuals but also supported by in-migration. Radiogenic strontium and oxygen isotope analysis of the Middle Horizon Tiwanaku colony at Rio Muerto, Peru, found that a small number of the people buried at Rio Muerto were born elsewhere and traveled as adults. Scholars suggest they may have been interregional elites, herders, or caravan drovers.

Collapse of Tiwanaku

After 700 years, the Tiwanaku civilization disintegrated as a regional political force. This happened about 1100 AD, and resulted, at least one theory goes, from the effects of climate change, including a sharp decrease in rainfall. There is evidence that the groundwater level dropped and the raised field beds failed, leading to a collapse of agricultural systems in both the colonies and the heartland. Whether that was the sole or most important reason for the end of the culture is debated.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL RUINS OF TIWANAKU SATELLITES AND COLONIES

- Bolivia: Lukurmata, Khonkho Wankane, Pajchiri, Omo, Chiripa, Qeyakuntu, Quiripujo, Juch’uypampa Cave, Wata Wata

- Chile: San Pedro de Atacama

- Peru: Chan Chan, Rio Muerto, Omo

SOURCES

The best source for detailed Tiwanaku information has to be Alvaro Higueras’s Tiwanaku and Andean Archaeology.

- Baitzel SI, and Goldstein PS. 2014. More than the sum of its parts: Dress and social identity in a provincial Tiwanaku child burial.Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 35:51-62.

- Becker SK, and Alconini S. 2015. Head Extraction, Interregional Exchange, and Political Strategies of Control at the Site of Wata Wata, Kallawaya Territory, Bolivia, during the Transition between the Late Formative and Tiwanaku Periods (A.D. 200-800). Latin American Antiquity 26(1):30-48.

- Hu D. 2017. War or peace? Assessing the rise of the Tiwanaku state through projectile-point analysis. Lithics: The Journal of the Lithic Studies Society 37:84-86.

- Janusek JW. 2016. Processions, Ritual Movements, and the Ongoing Production of Pre-Columbian Societies, with a Perspective from Tiwanaku. Processions in the Ancient Americas: Occasional Papers in Anthropology at Penn State 33(7).

- Janusek JW, Williams PR, Golitko M, and Aguirre CL. 2013. Building Taypikala: Telluric Transformations in the Lithic Production of Tiwanaku. In: Tripcevich N, and Vaughn KJ, editors. Mining and Quarrying in the Ancient Andes: Springer New York. p 65-97.

- Knudson KJ, Gardella KR, and Yaeger J. 2012. Provisioning Inka feasts at Tiwanaku, Bolivia: the geographic origins of camelids in the Pumapunku complex. Journal of Archaeological Science 39(2):479-491.

- Knudson KJ, Goldstein PS, Dahlstedt A, Somerville A, and Schoeninger MJ. 2014. Paleomobility in the Tiwanaku Diaspora: Biogeochemical analyses at Rio Muerto, Moquegua, Peru. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 155(3):405-421.

- Niemeyer HM, Salazar D, Tricallotis HH, and Peña-Gómez FT. 2015. New Insights into the Tiwanaku Style of Snuff Trays from San Pedro de Atacama, Northern Chile. Latin American Antiquity 26(1):120-136.

- Somerville AD, Goldstein PS, Baitzel SI, Bruwelheide KL, Dahlstedt AC, Yzurdiaga L, Raubenheimer S, Knudson KJ, and Schoeninger MJ. 2015. Diet and gender in the Tiwanaku colonies: Stable isotope analysis of human bone collagen and apatite from Moquegua, Peru. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 158(3):408-4Welcome to Amaruca, the Land of the Serpent Gods!

In his book, “New World Order: The Ancient Plan of Secret Societies“, William T. Still shows that America was called initially “The Land of the Plumed / Feathered Serpents” by the Indians of Peru.

James Pyrse researched an article written in the Theosophical Society magazine entitled “Lucifer”, which gave insight into the word “America.”

He says that the chief god of the Mayan Indians in Central America was Quettzalcoatl / Kukulkan (“Plumed Serpent”, “Feathered Serpent”). In Peru this god was called Amaru and the territory known as Amaruca.

Pyres states: “Amaruca is literally translated ‘Land of the Plumed Serpents’ (p. 45) – (Variation: ‘Land of the Great Plumed Serpents).” He claims that the name of America was derived from Amaruca, instead of after the explorer Amerigo Vespucci. This further proves that serpent worship was common throughout all cultures.

“In the most prevalent versions of American history, the origin of the name America is attributed to the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci (notice the reptilian beneath Vespucci’s feet, climbing a column representing America — just another ‘coincidence’, nothing to worry about).

“This popular distortion of the true origin of the native Amaruca (…) may be finally gaining more credibility among scholars to restore the name Amaruca to it’s rightful place.

Machu Picchu is located in Amaruca “Recent discoveries in Peru may lead to more conclusive evidence concerning the relationships between North and South American indigenous peoples. As discoveries continue to unearth ancient Incan cities, writings pertaining to the mysterious origins of Amaruca are sure to be found.

“The Incas abandoned their towns and cities and retreated from the treasure-hunting Spanish invaders after the Conquistadors captured and executed the last Incan leader, Tupac Amaru (i.e. ‘Shining Serpent’), in 1572. Some of the cities have since been rediscovered, but many more are believed to lie hidden in the dense jungle.” – Amaruca.com;

Why ‘Feathered Serpents’?

The obvious question is why would the native cultures call their home “The Land of the Feathered Serpents”?

Actually, the name should be interpreted as “The Land of the WINGED Serpents”, or even more to the point “The Land of the FLYING Serpents” – which meant that these serpents had the capability to fly.

It’s an easy analogy with the Egyptian ‘winged sun‘ (notice the serpents!), which in turn derives from earlier cultures, going back to the very first civilization on Earth: the Sumerians.

Flying chariots and dragons were also common depictions throughout ancient Asia, making this a global phenomenon.

In fact, in China, the dragon is a symbol of imperial authority.

“According to Chinese legend, both Chinese primogenitors, the earliest Emperors, Yandi and Huangdi, were closely related to ‘Long’ (Chinese Dragon). Since the Chinese consider Huangdi and Yandi as their ancestors, they sometimes refer to themselves as ‘the descendants of the dragon.’

“The dragon, especially yellow or golden dragons with five claws on each foot, was a symbol for the emperor in many Chinese dynasties. The imperial throne was called the Dragon Throne.” –