Neolin: the Delaware Prophet Who inspired Pontiacs Rebellion (Rogue One)

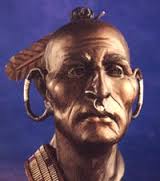

Neolin: the Delaware Prophet

Neolin: the Delaware Prophet

In 1762 the Delaware (Lenni Lenape) prophet Neolin, who was living in Ohio, had a vision in which he undertook a journey to meet the Master of Life. He was told:

“The land on which you are, I have made for you, not for others. Wherefore do you suffer the whites to dwell upon your lands?”“Drive them away; wage war against them; I love them not; they know me not; they are my enemies; they are your brothers’ enemies. Send them back to the land I have made for them.”

He received a prayer which was carved in symbolic language on a stick.

After returning from the vision, the prophet drew a map on a deerskin which was used in explaining his vision. This “great book” was sold to followers so that they might refresh their memories from time to time. The book showed the path of the soul from life to the afterlife.

Neolin’s vision provided the foundation for a pan-Indian movement. The influence of his religious movement spread throughout the Indian tribes in the Mississippi valley. Hundreds of Indians from different tribes were soon following his teachings. The pan-Indian nature of the movement overcame traditional animosities and created a new sense of cultural identity among the tribes. One of Neolin’s followers was the Ottawa chief, Pontiac.

Neolin’s vision provided the foundation for a pan-Indian movement. The influence of his religious movement spread throughout the Indian tribes in the Mississippi valley. Hundreds of Indians from different tribes were soon following his teachings. The pan-Indian nature of the movement overcame traditional animosities and created a new sense of cultural identity among the tribes. One of Neolin’s followers was the Ottawa chief, Pontiac.

Neolin’s followers went back to the old, traditional ways of Indian life. This meant that they gave up the use of firearms and hunted only with the bow and arrow. They ate dried meat and they drank a bitter drink recommended by Neolin. The drink had a purgative quality which was supposed to get rid of the poisons which their bodies had consumed as a result of European influence. They also dressed in animal skin clothing instead of the imported European cloth.

Neolin’s teaching opposed alcohol, materialism, and polygyny. He emphasized that if the Indians gave up the evil ways brought to them by the Europeans that the Master of Life would bless them with plentiful game.

According to ethnologist James Mooney, writing in 1896:

“The religious ferment produced by the exhortations of the Delaware prophet spread rapidly from tribe to tribe, until, under the guidance of the master mind of the celebrated chief, Pontiac, it took shape in a grand confederacy of all the northwestern tribes to oppose the further progress of the English.”

While Neolin’s message was anti-European, under Pontiac it became anti-British.

Many of Neolin’s followers felt that he was the reincarnation of Winabojo, the great teacher of the mythic past.

In 1763, Neolin urged the Three Fires Confederacy in Michigan-Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Potawamani-to expel the British and to join in Pontiac’s uprising.

Following the collapse of Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1765, Neolin’s influence as a pan-Indian spiritual leader waned.

Written history has recorded neither when Neolin was born nor when he died. In the historic record-the one maintained by non-Indians-he appears only as a brief note relating to Pontiac.

Neolin’s Vision

Neolin, a Lenni Lenape (Delaware) Indian, was a spiritual visionary who urged Native Americans to reject European influences and to revive tribal traditions that had waned in the generations since colonization. His philosophical movement drew from native faith as well as Christianity and was primarily concerned with moral improvement and attaining eternal salvation. At the same time, Neolin’s themes of self-empowerment and native separatism helped shape the ideas behind the Indian uprisings of 1763-1764, including Pontiac’s Rebellion. His message resonated with Indian audiences who shared a common sense of loss and desired to return their tribes to a life free of the intrusive British and French. As Neolin’s teachings spread, they inspired many Native American tribes to unite against their common colonial adversaries.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware Indians, had become familiar with the disruptions to native life caused by colonial expansion. In the century and a half since European contact, the Lenape people had sold or involuntarily ceded most of their ancestral lands along the mid-Atlantic seaboard, with many relocating to the Ohio River valley. They saw contagious diseases devastate nearly three-quarters of their population, and they had entangled themselves in wars driven by the ruthlessly competitive European beaver fur trade. The Lenape of the 1760s were heavily dependent on European trade goods, and had developed complicated and sometimes fraught relationships with neighboring European officials, traders, and missionaries. The British and French, as well as stronger tribes such as the Iroquois, had economically and politically marginalized the Lenape.

Neolin lived in the Ohio country, somewhere in the vicinity of the Lenape settlements at Tuscarawas or Cuyahoga. He reported his first revelations as a young man in 1760. In Neolin’s recounting of his visions, he had encountered a supreme deity called the Master of Life, or Great Spirit. The Master of Life declared to him that while Indians had a special relationship with their creator, they had been visited with divine punishments for both their moral failings and their abandonment of tradition. Wars between Indian tribes were offensive to the Great Spirit, as was striving after French trade goods, for these things had broken down the sense of native community. Most of all, however, the Master of Life was displeased that Indians had tolerated the arrival of Europeans, and especially that they had surrendered land to the newcomers. It was the Master of Life’s wish that America be reserved for Indians alone; by defying him, Indians had jeopardized their entry into heaven.

Some components of Neolin’s visions, including the idea of a distinctive covenant between the Master of Life and Native peoples, reiterated or built upon ideas that other Delaware prophets had espoused throughout the eighteenth century. His system of beliefs also clearly appropriated some elements from Christianity, with its native variations on heaven, hell, a single God, and the possibility of redemption from sin.

By 1762, Neolin had organized his visions into a plan for native spiritual renewal. Part of it involved purification of the body and soul. He outlined new dietary restrictions, praising the healthful virtues of corn while denouncing the destructive capacity of alcohol. He promoted new rituals for fasting and purging. He preached a return to native traditions, such as reviving the use of the bow and arrow for hunting and combat. Notably, he spoke out against longstanding native practices such as polygamous marriage and he condemned shamanic medicinal rituals as unholy witchcraft. In the long term, Neolin believed that only a complete separation from European society could save the souls of Native Americans. He exhorted natives to wean themselves from European (especially British) trade and return to a life of hunting and subsistence agriculture. This spirit of separatism, along with Neolin’s emotional appeals to tradition, proved to be instantly popular. He unsparingly blamed Indians for losing their way and corrupting their culture with European influences. Yet that acceptance of guilt might have also proved empowering, for many Native Americans saw it as an opportunity to take control and actively reject European encroachments on their way of life.

Though Neolin’s teachings were initially addressed to the Lenape people, his ideas spread rapidly. Native peoples hundreds of miles away, including the Ottawa chief Pontiac, adopted Neolin’s ideas as their own. The Delaware prophet’s visions amplified already strong Native resentments against the British, whose recent victories versus the French had generated deep anxieties about their future.

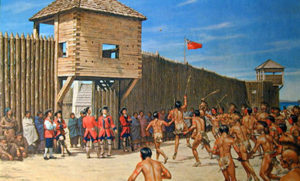

PONTIAC’S REBELLION INSPIRED BY THE TEACHINGS OF NEOLIN

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris brought the French and Indian War to a close. With England’s victory in the conflict, all French lands in North America now belonged to the British. American Indians in the Ohio Country feared the loss of their traditional ally and also believed that British settlers would be moving soon across the Appalachian Mountains. To prevent the incursion of whites, Chief Pontiac of the Ottawa encouraged Ohio Country American Indians to unite together and to rise up in 1763. The Ottawa attacked Fort Detroit in May 1763. Many people today view this as the beginning of Pontiac’s Rebellion. The Shawnee, the Munsee, the Wyandot, the Seneca-Cayuga, and the Lenape (Delaware) also raided British settlements in the Ohio Country and in western Pennsylvania during 1763. By late fall, Pontiac’s American Indian confederation had killed or captured more than six hundred people. Britain’s only garrisoned fort in the Ohio Country, Fort Sandusky, fell to the Ottawas that same year. The thirteen soldiers inside the fort were killed.

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris brought the French and Indian War to a close. With England’s victory in the conflict, all French lands in North America now belonged to the British. American Indians in the Ohio Country feared the loss of their traditional ally and also believed that British settlers would be moving soon across the Appalachian Mountains. To prevent the incursion of whites, Chief Pontiac of the Ottawa encouraged Ohio Country American Indians to unite together and to rise up in 1763. The Ottawa attacked Fort Detroit in May 1763. Many people today view this as the beginning of Pontiac’s Rebellion. The Shawnee, the Munsee, the Wyandot, the Seneca-Cayuga, and the Lenape (Delaware) also raided British settlements in the Ohio Country and in western Pennsylvania during 1763. By late fall, Pontiac’s American Indian confederation had killed or captured more than six hundred people. Britain’s only garrisoned fort in the Ohio Country, Fort Sandusky, fell to the Ottawas that same year. The thirteen soldiers inside the fort were killed.

In the autumn of 1764, the British military took the offensive against the American Indians.

In the autumn of 1764, the British military took the offensive against the American Indians.

Colonel John Bradstreet and Colonel Henry Bouquet each launched invasions of the Ohio Country from Pennsylvania. Most of the Wyandot and Ottawa, but not Pontiac, surrendered to Bradstreet in September due to a lack of ammunition. The American Indians, without their French allies, could not re-supply themselves with needed items. Bouquet forced the Seneca-Cayuga, the Shawnee, and the Lenape (Delaware) to surrender a month later. To avoid the British soldiers’ wrath, the three tribes had to return all captives, including those who still wished to live as American Indians. All of the tribes reluctantly complied. In early November, Bouquet’s army marched to Fort Pitt with more than two hundred former captives. Several fled back to the natives before even arriving at the fort.

Although Pontiac did not formally surrender to the British until July 1766, Pontiac’s Rebellion had ended in the autumn of 1764. The uprising clearly shows the difficulties American Indians in the Ohio Country faced with France’s withdrawal from North America. It also illustrates the tenuous grasp Britain had over the Ohio Country. Faced with large debts following the French and Indian War and fearful that further American Indian uprisings would drain the British treasury even more, Britain enacted the Proclamation of 1763. This act hoped to prevent further tensions between the British and the American Indians by forcing all colonists to live east of the Appalachian Mountains. The land west of the mountains was to be set aside for the American Indians. This act did briefly improve relations between the two sides. Yet colonists soon ignored the provisions and moved into the Ohio Country. New bloodshed quickly followed.