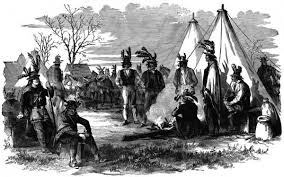

Because many children taken as captives had been adopted into Native families, their forced return often resulted in emotional scenes, as depicted in this engraving based on a painting by Benjamin West.

Native History: White Child Abducted by Delaware Embraced Native Life

This Date in Native History: On May 21, 1758, Delaware Indians kidnapped a child named Mary Campbell from her home in western Pennsylvania and held her captive during the French and Indian War.

By some accounts, Campbell was 10 at the time of her abduction, while other sources claim she was 12. She likely lived with the Delaware (also known as the Lenape) in what is now Summit County, Ohio, for about six years, said Michael Cohill, a historian in Akron, Ohio. She was repatriated in 1764 during the famous release of captives at the conclusion of Pontiac’s War.

Campbell, known as the first white child on the Western Reserve, was one of several known abductees captured during the war, Cohill said. Often, white women or children were taken to replace Natives killed in the conflicts over frontier land.

“If someone came into your city and killed a couple of your children, then your husband would go out and attack a village of white people and take their women, take their children,” Cohill said. “If you kill my children, I’m going to take yours as my own and raise them.”

The abduction probably was traumatic, Cohill said. Captives were transported from their homes to Native villages that sometimes were great distances away. Some captives died during the journey while others—those who did not cooperate—were killed.

Those who survived quickly assimilated to Native life, Cohill said.

“If you lived through the capture and traveling, you would do everything you needed to do to decide you belonged with these people and not make any attempt to leave,” he said. “If you did not cooperate with your captors, they killed you.”

Records of Campbell’s abduction reveal that her family went to great lengths to bring her home. A notice printed in October 1764 in The Pennsylvania Gazette describes Campbell as a child of 10 with red hair and freckles.

In the notice, Campbell’s father “begs that she may, by all good people, be helped on her way to him, as he, and her aged mother are very desirous of seeing her.”

Kidnappings like Campbell’s came after the tribe lost almost 90 percent of its people to war and disease, said Michael Pace, an artist in residence at Conner Prairie, a living history museum in central Indiana. After an outbreak of German measles reduced the tribe to 3,000 members, the Delaware sought white women and children to help replenish its dwindling numbers.

Yet many captives, including Campbell, discovered that life among the Natives was better than what they left behind, said Pace, a former assistant chief for the Delaware Tribe of Indians.

“People were treated better in the tribe than they were in white society—especially women,” he said. “They were raised in a matrilineal society, where they had rights and were treated better.”

Once removed from the male-dominated white society, women did well among the Natives, Pace said. Abductees who were rescued from the tribes often ran away from home to rejoin their Native families.

“I’m sure there was a great deal of fear when people were abducted, but they began to realize they were treated well,” Pace said. “People cared about them, wanted them to learn how to live this life. Their ideals changed.”

For Campbell, life among the Delaware probably was “extraordinarily wonderful,” Cohill said. He believes Campbell, who was 16 or 18 when her captivity ended, was forcibly repatriated. He also believes Campbell married within the tribe and likely had children she left behind when she returned home.

By the end of Pontiac’s War, white people living in Ohio were there by choice, Cohill said. Some captives refused repatriation and did not return to their former homes.

“Those that didn’t go back, there was a reason for them not to return,” he said. “Usually they were married, were parents, and that meant they would never be accepted back into white society.”

After her repatriation, Campbell settled in Washington County, Pennsylvania. She married a white settler in 1770 and had seven children.

Wikipedia

Memorial to Mary Campbell, placed just outside Mary Campbell Cave.

But Campbell never fully recovered from her capture—or her return, Cohill said.

“We do know that the taking was horrible, just as much as the return was horrible,” he said, calling Campbell’s adult life a “sad story.” He pointed to accounts recorded by Campbell’s children, who said their mother often retreated into the woods to cry.

“It was five to seven years later that she returned, so she was old enough to be married, to have children,” he said. “Being a woman in a Delaware tribe, she would have been at an exalted position. It was a matriarchal society and they took extraordinarily good care of their children.”

Campbell died in 1801, and was buried near her western Pennsylvania home.

https://www.facebook.com/TGEARTISWAR/videos/686766714827424/