The Huge, Ignored Uprising in the Andes

The Huge, Ignored Uprising in the Andes

The Tupac Amaru Rebellion

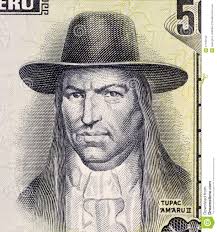

Tupac Amaru II, the late-eighteenth-century leader of the Peruvian rebellion against the Spanish crown

Between 1780 and 1782, when the rebellion of the British colonists in North America was reaching its climax, a still more savage drama was being played out in South America. The Andes were in revolt, and Spain, like Britain, was faced with the prospect of losing one of its most prized overseas possessions. Since the overthrow of the Inca empire in the 1530s and the discovery of the silver mountain of Potosí in the high Andes in 1545, the viceroyalty of Peru had generated a substantial part of the wealth that enabled Spain to create and maintain its “empire of the Indies” and its position as a leading European power. Now suddenly in 1780 Spain saw its control of Peru placed in jeopardy by a minor Indian nobleman, José Gabriel Condorcanqui, who laid claim to the royal blood of the Incas as a direct descendant of the last Inca ruler, Tupac Amaru, captured and executed by the Spaniards in 1572.

The rebellion of Tupac Amaru II, as Condorcanqui came to style himself, was the largest and most dangerous rebellion faced by the Spanish crown in its American empire before the great upheavals of the early nineteenth century that culminated in its loss. Although there had been innumerable disturbances and uprisings over the course of some two and a half centuries of Spanish imperial rule, these had for the most part been fairly small-scale and localized, and were suppressed with relative ease. This was partly because of the coercive power at the disposal of the imperial authorities once they chose to deploy it, but much of the relative tranquility of the new multi-ethnic societies that emerged in the wake of conquest can be attributed to the system of government that evolved as Spain’s Habsburg rulers imposed elaborate judicial and administrative structures on the conquered territories.

Under this system, Spaniards and creoles (their American-born descendants), the indigenous peoples (all subsumed under the name of “Indians”), and a growing population of mestizos, of mixed Indian and European ancestry, with the further addition of African blood as increasing numbers of slaves were imported, were all nominally welded into one organic whole, whether in the viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico) or in that of Peru. Each was conceived as a Christian commonwealth ruled by a distant but allegedly beneficent monarch and watched over by a ubiquitous church. Within this hierarchically organized society each section of the community theoretically possessed its own allotted space. A native elite of caciques, or kurakas as they were known in Peru, served as intermediaries between the royal authorities and the indigenous population; and every individual or community had the right of appeal up the bureaucratic chain to the king himself. This system left room for maneuver both to the rulers and the ruled. How,…

|

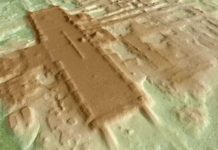

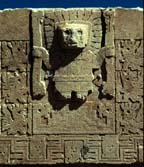

Tupac Amaru, The Life, Times, and Execution of the Last Inca In 1533 Francisco Pizarro, after killing Inca Atahuallpa, marched from Cajamarca, Peru, towards the Incan After escaping from his jail, the Saxsayhuaman fortress, Manco Capac organized an army and attacked Cuzco in 1536. So began the belated resistance to the Spanish conquest in South America. Firing red-hot stones with slings the resistance set their occupied sacred city, Cuzco, afire. The Spaniards retreated to the Saxsayhuaman fortress, where their force of 200 with superior armaments held off Manco Capac’s force of 40,000 to 50,000. The Incans were unable to adapt to the Spanish weapons. Although they captured some firearms, they were unable to use them. Due to the onset of planting season many of the rebels abandoned the uprising. Manco Capac’s forces prematurely ended the siege and altered their strategy. They moved to Ollantaytambo to wage a war of attrition on the conquerors. When driven from Ollantaytambo the Incas retreated to the more remote and difficult to access Vitcos, a town in the rugged and nearly impenetrable Vilcabamba Andes. From their remote mountain location Manco Capac directed the harassment of the Europeans, making it impossible for the Spaniards to establish settlements anywhere in southern Peru. Meanwhile, Paullu was crowned puppet Inca in Cuzco. |

Cobo, Bernabe, Historia del Nuevo Mundo, bk 12. Coleccíon de documentos inéditos relativos al descubrimiento, conquista y organización de las antiquas posesiónes españoles de Ultramar, ed. Angel de Altolaguirre y Duvale and Adolfo Bonilla y San Martin, 25 vols., Madrid, 1885-1932, vol.15. In Hemming. García de Castro, Lope, Despatch, Lima, Mar. 6, 1565, Gobernantes del Perú, cartas y papeles, Siglo xvi, Documentos del Archivo de Indias, Coleción de Publicaciones Históricas de la Biblioteca del Congreso Argentino, ed. Roberto Levillier, 14 vols., Madrid, 1921-6. In Hemming. Guillen Guillen, Edmundo, La Guerra de Reconquista Inka, Historica epica de como Los Incas lucharon en Defensa de la Soberanía del Perú ó Tawantinsuyu entre 1536 y 1572, Primera edición, ímpeso en Lima, El Perú. Hemming, John, The Conquest of the Incas, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., New York, 1970. Markham, Sir Clements, The Incas of Peru, Second Edition, John Murray, London, 1912. Métraux, Alfred, The History of the Incas, Translated from the French by George Ordish, Pantheon Books, New York, 1969. Mura, Martín de, Historia General del Perú, Orígin y descendencia de los Incas (1590 – 1611), ed. Manuel Ballesteros-Gaibrois, 2 vols., Madrid, 1962, 1964. In Hemming. Ocampa, Baltasar de, Descripción de la Provincia de Sant Francisco de la Vitoria de Vilcapampa (1610). Trans, C. R. Markham, The Hakluyt Society, Second Series, vol. 22, 1907. In Hemming. Salazar, Antonio Bautista de, Relación sobre el periodo del gobierno de los Virreyes Don Francisco de Toledo y Don García Hurtado de Mendoza (1596), Coleción de documentos inéditos relativos al descubrimiento, conquista y colonization de las posesiones espanolas en América y Oceanía sacadas en su mayor parte de Real Archivo de Indias, 42 vols., Madrid, 1864-84. In Hemming. Titu Cusi Yupanqui, Inca Diego del Castro, Relación de la conquista del Perú y hechos del Inca Manco II; Instrución el muy Ille. Señor Ldo. Lope García de Castro, Gouernador que fue destas rreynos del Pirú (1570), Coleción de libros y documentos referentes a la historia del Perú, ed. Carlos A. Romero and Horacio H. Urteaga, two series, 22 vols., Lima, 1916-35. In Hemming. Valladolid, 29 April 1549, Colección de documentos para la historia de la formación social de Hispano-América, ed. Richard Konetzke, 4 vols., Madrid, 1953. In Hemming. Vargas Ugarte, Ruben, Historia del Perú, Virreinato (1551-1600), Lima, 1949, p. 258.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Many of the translations in this article are quoted from the work of John Hemming. Hemming’s work, Conquest of the Incas, is both a major work of excellent scholarship and an enthralling narrative. I highly recommend the book to those seeking further authoritative information and greater detail about one of the most tragic genocides in human history. I receive many inquiries due to this page, and I direct most of them to Hemming’s publications. Thanks are extended to Tom Shoemaker for his editing help and to Peruvian native Frank Fernandez for comments and a helpful correction. NOTES: Aug. 2006. I received a careful review of a passage in the article from Manuel J. Inguanzo. I had written, “At the age of eight or nine Beatriz Clara Coya, the daughter of Sayri Tupac and heiress to his great estates, was wedded to Cristóbal Maldonado and then raped by him to give greater force to the wedding claim. This was done in an attempt to secure her inheritance.” Manuel noted, other histories do not report this marriage actually taking place, and he kindly provided further details. Manuel Inguanzo, summarizing Spanish language histories he found on the topic, reported, “The royal child was raised by the nuns of the convent of Santa Clara in Cuzco until she was eight years old, when her mother took her to the house of Arias Maldonado, an influential conquistador. In that household, plans were laid our to marry her to Cristobal, brother of Arias Maldonado. … It was even murmured that Cristobal Maldonado had raped the child Beatriz Clara in order to force a marriage to take place. … Titu Cusi Yupanqui, as a condition to abandon the refuge in Vilcabamba, which had been so irritating to the Spanish crown, wanted the authorization of the marriage of his son Quispe Tito to the girl… doña Beatriz was returned to the convent where she stayed until she turned 15 years old, when at the behest of the viceroy Francisco de Toledo, she indicated her preference for marriage. The viceroy Toledo gave her in marriage to a captain in his retinue, Martín García de Loyola, as a reward for having captured and taken in chains to Cuzco Tupac Amaru…” Sources: Diccionario histórico-biográfico del Perú. Tomo segundo, Manuel de Mendiburu Lima, Imprenta de J. Francisco Solis, 1876, and http://www.cervantesvirtual.com, entry: Doña María Coya de Loyola Inca. |

Early Monumental Architecture on the Peruvian Coast The Cannibalism Paradigm: ANDES WEB RING – ANDEAN PHOTO GALLERIES: Your comments, etc. are appreciated. Contact. |

When civil war broke out among the conquerors Manco Capac sided with Almagro against Pizarro. Upon defeat Almagro fled towards Vitcos in the Vilcabamba valley. He was captured en route. Seven of Almagro’s followers managed to escape Pizarro and were given refuge by Manco Capac. He ordered that they should have houses, “treating them very well and giving them all they needed. He even ordered his own women to prepare their food and drink” (Titu Cusi Yupanqui 74). In 1544 these seven assassinated the Inca, their host and protector of two years, by stabbing him in the back while playing horseshoes. After repeatedly stabbing the defenseless Inca the seven men escaped on horseback. Their escape plan failed when they took a wrong turn. They were found and executed the following day.

When civil war broke out among the conquerors Manco Capac sided with Almagro against Pizarro. Upon defeat Almagro fled towards Vitcos in the Vilcabamba valley. He was captured en route. Seven of Almagro’s followers managed to escape Pizarro and were given refuge by Manco Capac. He ordered that they should have houses, “treating them very well and giving them all they needed. He even ordered his own women to prepare their food and drink” (Titu Cusi Yupanqui 74). In 1544 these seven assassinated the Inca, their host and protector of two years, by stabbing him in the back while playing horseshoes. After repeatedly stabbing the defenseless Inca the seven men escaped on horseback. Their escape plan failed when they took a wrong turn. They were found and executed the following day.

The Spaniards in Cuzco knew nothing of what had transpired. Two envoys sent were each in turn not allowed to enter the province and failed to contact the Inca. Also, the Spaniards had failed to send the tributes promised to the Inca in the treaty of Acobamba. A third envoy was killed by an Indian captain at the border, and this incident became known in Cuzco.

The Spaniards in Cuzco knew nothing of what had transpired. Two envoys sent were each in turn not allowed to enter the province and failed to contact the Inca. Also, the Spaniards had failed to send the tributes promised to the Inca in the treaty of Acobamba. A third envoy was killed by an Indian captain at the border, and this incident became known in Cuzco. Three groups of pursuing Spanish soldiers returned. One group had captured Tuti Cusi’s son and pregnant wife. A second returned with prisoners and a million in gold, silver and emeralds, which was divided between the soldiers and priests. The third group returned with Tupac Amaru’s two brothers, other relatives and several of his generals. The Inca and his commander remained at large. A group of forty hand-picked soldiers set out to pursue them. They followed the Masahuay river for 170 miles, where they found an Inca warehouse with quantities of gold and the Inca’s tableware. Captured Chunco Indians reported that Tupac was down river in Momorí. Expedition leader García de Loyola ordered the building of five rafts and pursued the Inca, surviving turbulent rapids en route.

Three groups of pursuing Spanish soldiers returned. One group had captured Tuti Cusi’s son and pregnant wife. A second returned with prisoners and a million in gold, silver and emeralds, which was divided between the soldiers and priests. The third group returned with Tupac Amaru’s two brothers, other relatives and several of his generals. The Inca and his commander remained at large. A group of forty hand-picked soldiers set out to pursue them. They followed the Masahuay river for 170 miles, where they found an Inca warehouse with quantities of gold and the Inca’s tableware. Captured Chunco Indians reported that Tupac was down river in Momorí. Expedition leader García de Loyola ordered the building of five rafts and pursued the Inca, surviving turbulent rapids en route.

Tupac Amaru calmly raised his hands and silence and motionlessness fell upon the densely packed crowd. Several versions survive of the Inca’s speech. In one report Tupac spoke and implored the crowd to never curse their children for bad behavior, but only to punish them, for once he had annoyed his mother and she cursed him with an unnatural death. The priests convinced him that his death was the wish of God. He asked forgiveness of everyone and told the Viceroy he would pray to God for him. Bishop Popoyán and some priest implored the Viceroy to send Tupac Amaru to Spain to be tried by the king. The viceroy, Francisco de Toledo ordered Juan de Soto, his servant and law officer of the court through the crowd to the center of the spectacle. He galloped furiously to the gallows with the Viceroy’s order that the Inca’s head be cut off at once, crushing many people in the crowd.

Tupac Amaru calmly raised his hands and silence and motionlessness fell upon the densely packed crowd. Several versions survive of the Inca’s speech. In one report Tupac spoke and implored the crowd to never curse their children for bad behavior, but only to punish them, for once he had annoyed his mother and she cursed him with an unnatural death. The priests convinced him that his death was the wish of God. He asked forgiveness of everyone and told the Viceroy he would pray to God for him. Bishop Popoyán and some priest implored the Viceroy to send Tupac Amaru to Spain to be tried by the king. The viceroy, Francisco de Toledo ordered Juan de Soto, his servant and law officer of the court through the crowd to the center of the spectacle. He galloped furiously to the gallows with the Viceroy’s order that the Inca’s head be cut off at once, crushing many people in the crowd.

The men had honest and useful occupations. The lands, forests, mines, pastures, houses and all kinds of products were regulated and distributed in such sort that each one knew his property without any other person seizing it or occupying it, nor were there law suits respecting it…

The men had honest and useful occupations. The lands, forests, mines, pastures, houses and all kinds of products were regulated and distributed in such sort that each one knew his property without any other person seizing it or occupying it, nor were there law suits respecting it…