A Look at a Tri-Racial Group (author unknown)

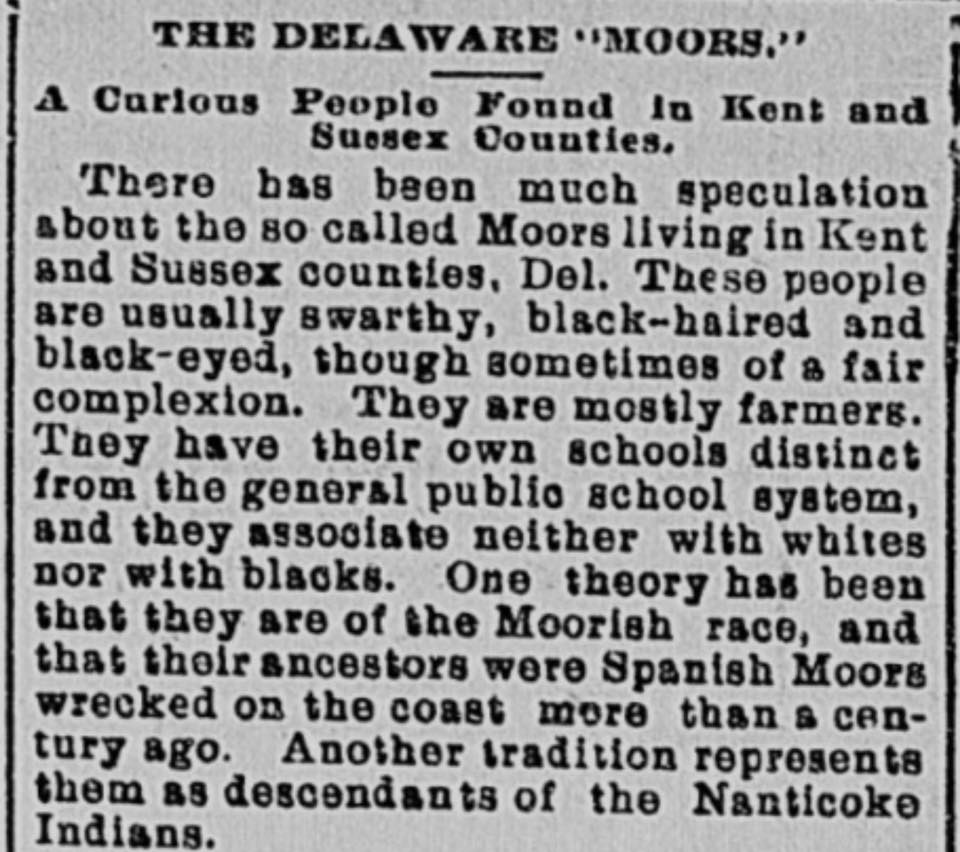

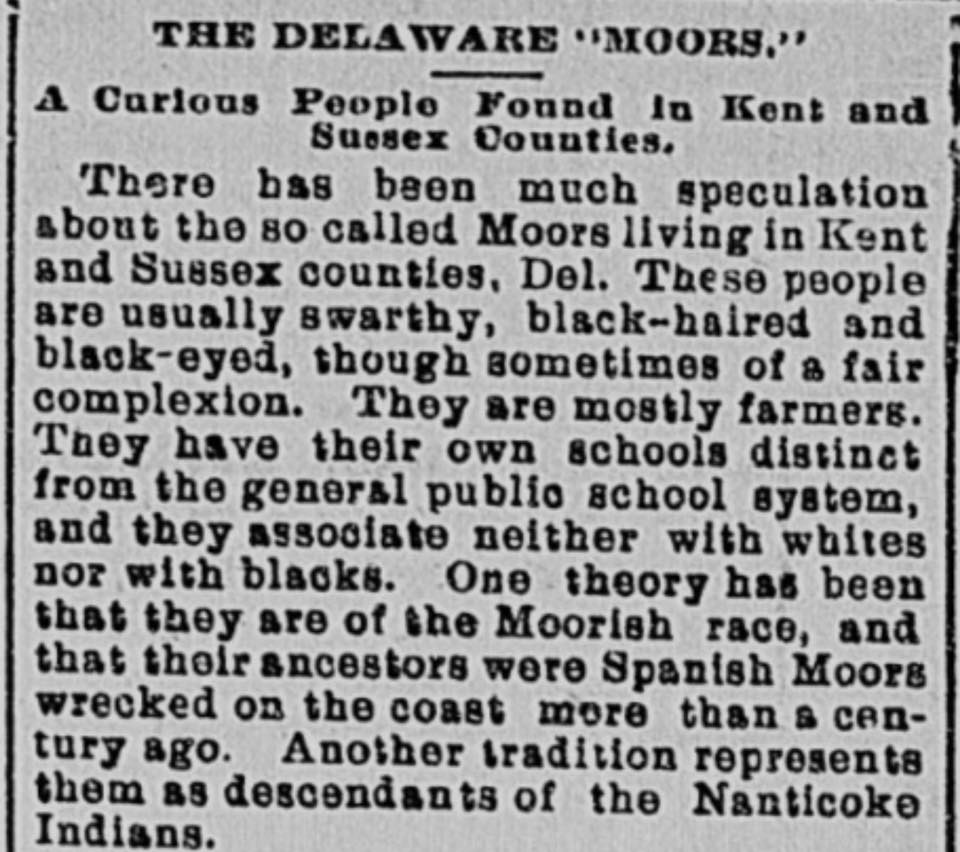

An intermingling of races was one of the products which occurred with the early European exploration and settlement of the North American continent. Stemming from these earlier interminglings, there exists within the Eastern United States today, in numbers totaling between fifty thousand and one hundred thousand persons, a variety of surviving, localized strains of mixed blood peoples.1 Those called the Moors or the Delaware Moors are a group of such descent.

In a June, 1953 article, the geographer, Edward T. Price, mapped the locations of the chief populations of racially mixed groups in the Eastern United States (see Fig. 1).2 Through the particular geographic distributions of these groups, Price indicated how environmental circumstances, such as swamps or inaccessible and barren mountain country, favored their growth. Many of the groups are located along the tidewater of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts where swamps, islands, or peninsulas have protected them and kept alive a portion of the aboriginal blood which greeted the first white settlers on these shores. Other pockets of these groups are located farther inland, in the Western Piedmont area, backing up against the Blue Ridge and Alleghenies. A few of the groups are to be found along the top of the Blue Ridge, and on several ridges of the Appalachian Great Valley just beyond.

In addition to mapping the distribution and indicating environmental circumstances pertaining to these racially mixed groups, Price also noted a number of common phenomenon related to them. These groups have been presumed to be part white, with varying proportions of American Indian and Negro blood, although a lack of solid documentation concerning the origins of a good number of the groups makes determination of racial composition uncertain. Due to their particular racial mixtures, these groups are recognized as of intermediate social status, sharing lots with neither writes nor blacks, nor enjoying the government protection or tribal ties of typical Indian descendants.

Old census records have indicated that the present number of mixed bloods have sprung from great reproductive increases of small initial populations of the groups.3 The predominance of a limited number of surnames within each group at present is in line with such a conclusion, and is also indicative of their high degree of endogamy, resulting from their intermediate status and their relative geographic isolation from the mainstream population. Characteristics of generally lower educational and income levels, as well as large families, tend to further mark the racially mixed groups as members of the more backward sector of the American nation.

While all of the aspects mentioned above are descriptive of similarities between the various racially mixed groups distributed throughout the eastern United States, one must also realize that each group is essentially a unique phenomenon. Each one stems from a particular intermixture of races, and is related to a specific locale with recognition of the group crystallized by a name applied, either by the group itself or, by the people surrounding them in their region.

The phenomena which Price noted as common denominators in his analysis of racially mixed groups generally hold true for the people called Moors, who reside in the Kent and Sussex Counties of Delaware, and across the Delaware Bay in Southern New Jersey.

Concentrations consisting of members of this group are located in lowland, tidewater areas of the two states, areas which are basically rural, even today. (See map, Fig. 2). Moors make up the largest portion of the total population, (a little over three hundred persons), of the small community of Cheswold, Kent County , Delaware . (Cheswold is about five miles north of the larger state capital, Dover). These people also inhabit the rural area surrounding Cheswold. A number of Delaware Moors make their homes in and around the small town of Millsboro, and along the north shore of the Indian River in Sussex County, Delaware. In addition to the Moors living in and around Cheswold and Millsboro, Delaware, a similar, but more dispersed, number of Moor families live in rural, southern New Jersey. One finds Moor families in the farming territory outside of Bridgeton, Millville, and Vineland, New Jersey.

The location of the Cheswold community does not, at first, seem to concur with Price’s indications that racially mixed groups flourish in relatively isolated geographic areas. The fact that Cheswold is so near to Dover, and also, just west of a major state highway, Delaware Route 13, is at variance with that thesis. However, farmlands have served somewhat as a buffer between Cheswold and Dover, and the Moor community has remained, up to the present, a separate entity. Information concerning the settlement in Cheswold by the Moors is more akin to Price’s thesis.

There are indications that Cheswold was not the initial settlement area for this group of Moors. Informant Wilson Davis, a Delaware Moor, stated that the Moors of Cheswold originally lived about ten miles to the northeast at Woodland Beach, a more marshy area along the Delaware Bay. According to Mr. Davis, the Moors moved to farm farther inland and to settle in Cheswold during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as the result of a large storm which inundated much of the land surrounding Woodland Beach.4

The Moorish areas in Sussex County, Delaware and in southern New Jersey are in more sparsely populated, rural regions. In both regions, the landscape is covered by truck farms or dense pine forests, and neither area is crisscrossed by major traffic routes.

Geography has played some part in setting the Moors start from the mainstream American population, but the racial composition of this group, linked to their origins, has played a more primary role. A number of scholars have taken note of this group which, for the most part, considers itself distinct from both Negro and white races. Researchers have examined their mixed blood characteristics and have endeavored to trace the precise origins of the Moors.5

In discussing the physical appearance of the Moors, as well as the Nanticoke Indian descendants to whom some Moors are related, C. A. Weslager wrote:

certain facial characteristics…set them apart from both whites and Negroes. The darkest have brown skins and the lightest resemble their white neighbors in complexion. Blonde, red and sandy hair may be seen, but the majority have brown or black hair, either wavy or straight and coarse like that of the full blooded American Indian. Kinky or woolen hair…is not often seen…straight noses and thin lips are typical. Eye colors range from grays and blues to dark brown and black. Many of the mixed bloods have sharply chiseled features, swarthy complexions and straight hair…. Others are distinctly Indian-like in appearance, having high and wide cheekbones, even among the same family. Light skinned Parent often have dark skinned children and vice versa. 6

No one has really been able to trace the precise origins of the Delaware Moors. Legend and historical hearsay have suggested possibilities. C. A. Weslager, in his book Delaware’s Forgotten Folks, presents (in his own words) legends of three categories which he collected from Delaware Moors.7 One category of legend purports that the Moors originated sometime before the Revolutionary War through the founding of a colony along the Atlantic coast of the Delmarva peninsula by a group of dark skinned Spanish Moors. Through intermarriage with the local Indians come the people called Moors in Delaware and New Jersey.

A second category of legend Weslager refers to as pirate legends. These legends stated that Spanish or Moorish pirates, in the later eighteenth century, were shipwrecked off the Delaware coast in the Delaware Bay or near the Indian River Inlet. The shipwrecked men were taken in by the Nanticoke Indians and came to marry Indian women, thus beginning the mixed stock of Delaware Moors. Some versions of this legend considered the shipwrecked men as Spanish, French, or Moorish sailors and not buccaneers.

Weslager categorizes a third legend type, which he found most popular among the Moors, as romantic legend. In this legend type a beautiful woman and a dark-skinned slave or slaves are the central characters. The woman was wealthy, either Spanish or Irish, and lived on a plantation in southern Delaware. She purchased one male slave who turned out to have been a Spanish prince. They then fell in love and had children of dusky complexion. Not being accepted by the white community, the family sought associations elsewhere and consequently, mixed with the Indians in the vicinity of the plantation. Other modifications of this plot said that a similar women bought seven couples of Moorish slaves whose children intermarried with Indian descendants living on Indian River.

Historically, there is foundation for the legends of the pirate category. Piracy was common in the Delaware Bay from about 1685 to 1750, and references cite occurrences of Spanish and French pirates preying on ships that entered the Delaware Bay.8 William Kelly, a citizen of Lewes, Delaware, was captured and taken aboard a French pirate ship in 1747. According to him the pirate crew of one hundred and thirty members consisted of “some English, some Irish, and some Scotch, but the most part of them were Frenchmen and Spaniards.”9 In 1717, Delaware authorities issued a proclamation stating that they were willing to grant pardon to privateers who surrendered to the law and gave up their looting careers.10 In these ways pirates could have ventured to settle along the Delaware coast and engendered the Moorish strains in the existing local population.

However, this does not account for the fact that most of the surnames of the Delaware Moors suggest English descent. One researcher, Donald VanLear Downs, has endeavored to trace the origins of the Delaware Moors through an expedition launched in the 1680’s by Charles II of England to Tangiers in North Africa. Downs employed as sources extracts from the “Calendar of State Papers–Domestic, October 1683 to April 1684” filed in the British Museum in London, and an oral account he received from a Tangier historian, a Mr. Maxwell Blake. Downs asserted that the Moors in Delaware have English surnames because a number of Charles II’s companies, when disbanded in 1684, set sail for America accompanied by Moorish women. They supposedly landed on an island in the Chesapeake Bay and named it Tangier Island.11Down’s assertions may explain how Moorish blood reached the region, but they do not offer explanation as to why no Moors presently inhabit Tangier Island, or why a migration occurred from this possible initial settlement to the Indian River, Woodland Beach, or Cheswold areas of Delaware.

Although the specific origins of the Delaware Moors is unclear, most scholars and the Moors themselves, have tended to come to the consensus that the group can be identified as being a racial mixture of the Indians who once occupied the Delmarva region (the Nanticokes and the Lenni Lenape), of whites of European descent, and of some unspecified African strain. Also agreed upon is that the Moors of Delaware have come to be related, by blood and marriage ties, to the Nanticoke Indian descendants of Indian River Hundred, Sussex County, Delaware.

Returning to Price’s thesis concerning tri-racial groups, one finds that, as with other groups, the Delaware Moors developed their particular racial mixture in much earlier times, (in this case, during the Colonial period), and that the present numbers in the group are descendants of that earlier mixed population. According, to written sources and informants, it has been customary for Moors to marry Moors.12 Because of this endogamy, the Delaware Moors today, as a group, consist of members of closely interrelated families. Informant Dorothy Carney listed eighteen Moor families of Cheswold and stated that branches of some of these families make up the Moor populations in both Sussex County, Delaware and in southern New Jersey.13

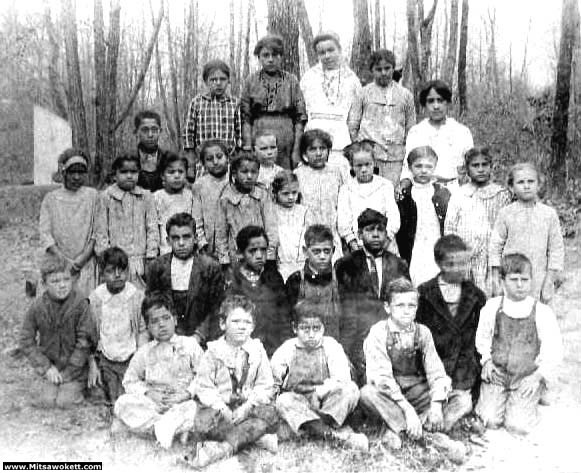

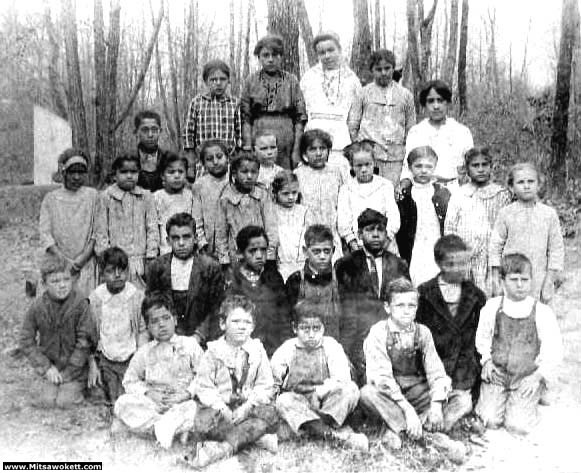

Price generalized that most tri-racial groups tended to have larger immediate families and lower educational and income levels than the mainstream population. None of my sources seemed to indicate that the Delaware Moors have larger than average numbers of offspring. However, in terms of education, most Moors do not progress beyond the high school level, and a good number of the Moors attended only grammar school. Relatively low educational attainment by the Moors as a group has been due, in part, to racial discrimination. Previously, in the Cheswold area, the Moors were barred from attending local white public schools, and many Moor parents did not wish their children to attend the separate black public schools. It was in 1923 that Pierre Samuel DuPont financed the erection of a three room schoolhouse to serve as the state-supported Cheswold School for the Moor children of grammar school ages.

The Cheswold School functioned as the primary educational Institution for the Moors of Cheswold until it was closed in 1964, along with the Fork Branch grammar school, (also built by P. S. DuPont in the twenties, and intended for blacks, though attended mainly by Cheswold area Moor children). It was not until the late 1950’s, after the 1954 Supreme Court ruling and when school consolidation occurred, that Moor children could attend public high schools in the Dover area, and then more could pursue a college education. Prior to that time, numerous Moors did not attend high school, though some did enroll in correspondence courses and received high school diplomas by taking an equivalency examination.

In terms of occupation, most Moors have been tenant- or landowning farmers and have earned moderate and respectable incomes from working the land, thus not needing higher academic educations. The male Moors who entered the labor pool in non-farming occupations with no higher education found various blue-collar level jobs in construction, maintenance, or factory work, for example. The Moor women who have worked have done so in factory work, as domestics or as sales persons in retail stores.

Some persons who have previously investigated the Delaware Moors have considered them no different outwardly from other rural or small town Delawareans. Other writers have felt the Moors maintain their own peculiar traditions. When doing field research among the Delaware Moors in the early 1940’s, C. A. Weslager claimed that “beneath the surface lurk shadows that can be traced to Indian life of the past.”14 He cited the lingering use of herbal cures, weather beliefs related to natural phenomena, and handmade wooden implements as survivals of the Moors’ Indian descent.15 It seems to this researcher that a good number of the survivals which Weslager maintained as being Delaware Moorish, (such as sassafras tea, the belief that molesting a buzzards nest would bring misfortune, or the use of animal traps made of logs and tree limbs, were also passing traditions of many other rural Delawareans at the time. Donald Downs also indicated in 1960 that the Delaware Moors16 “have many traits and a few customs of the ‘Moors’ of Morocco.”

Mr. Downs did not elaborate on just what these traits and customs might be and my research turned up nothing strikingly Moroccan. It does not appear that a peculiar lifestyle or variant traditions have been the elements marking the Delaware Moors as an identifiable group. Strong family ties and separate social structures do seem to be forces maintaining a “groupness” among them.

Informants indicated that most social affairs for the Moors are and have been family affairs.17 Both Mrs. Dorothy Carney and Wilson Davis recall “Big Thursdays” which were held annually at Woodland Beach on the second Thursday in August. This was an all-day affair of picnicking and entertainment such as swimming, dancing, wrestling, and foot races. Wilson Davis says that it was strictly a Moor affair, a time when relatives from Cheswold, lower Delaware, and from New Jersey came together and the whole clan had a reunion.18 The last big crowd was in about 1934, according to Mr. Davis, and Mrs. Carney says the tradition ended due to family feuding.

But family ties are still strong among the Moors. Mrs. Carney’s family gathers regularly with relatives for Sunday dinners in the winter and has had picnics every summer Sunday with relations for at least the last ten years. Birthday celebrations are causes for large family gatherings, also.

Volunteer fire companies, schools, and churches are institutions which often serve as social centers in small towns. In Cheswold, Moors are still barred from serving on the firefighting crew, although they virtually support the weekly bingo games held at the fire hall. Mrs. Carney stated that when the Cheswold School operated dances, raffles and box socials were events held to support school programs and as get-togethers for the Moors.

The Rev. John VanTine serves as pastor for both the Methodist churches in Cheswold, the Cheswold United Methodist Church functions for a predominantly white congregation while the Immanuel Union United Methodist Church serves the Moors of the Cheswold area in religious and social capacities. Sunday services, as well as social events such as suppers, raffles, and occasional talent nights featuring spiritual songs or makeshift bands, bring a sizable group of Cheswold Moors together frequently. Homecoming days, held about once a year at the church, to honor some of the older Moor families with recognition during the service and a supper, draw Moors from Cheswold and farther areas, especially those closely related to the honored families.

The clannish nature of the Delaware Moors and the existence of their own network of organizations and institutions have, in good part, been created by the dynamics of prejudice and racial discrimination. These elements which in some ways set the Moors apart, are not due to significant cultural differences between the Moors and their mainstream counterparts. As with other minorities, the Moors have often been barred from the cliques, social clubs, and churches of white America. Consequently, they have needed to construct to a certain extent their own parallel social world.

There are now many interests served by the preservation of this separate communal situation; it is doubtless that many of the Moors are psychologically most comfortable in it, even though they desire that discrimination in such areas as employment, education, and housing be eliminated. This is slowly happening as the climate of the nation of the whole end of the particular regions inhabited by the Moors become more tolerant toward racial minorities. While the Moors have long been behaviorally assimilated into mainstream American life, they are still in the process of becoming structurally or institutionally assimilated. As long as there are needs to be served by such strong family ties and parallel social structures, the Moors of Delaware and southern New Jersey will remain a viable and identifiable group.

Footnotes

1. Edward T. Price, “A Geographic Analysis of White-Indian-Negro Racial Mixtures in the Eastern United States,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Vol. 43, No. 2, p. 136.

2. Ibid.

3. Two indexed publications particularly useful to Price were: U. S. Census Bureau, Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, (Washington, 1907-1908); C.G. Woodson, Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830, (Washington, 1925).

4. Untaped interview with Wilson Seville Davis, May 24, 1974. (Mr. Davis, a Delaware Moor who grew up in Clayton, DE, is sexton of Christ Episcopal Church, Greenville, DE. He is keenly interested in the origin and history of the Delaware Moors, particularly as a result of his conversion to the Mormon religion with its emphasis on genealogy).

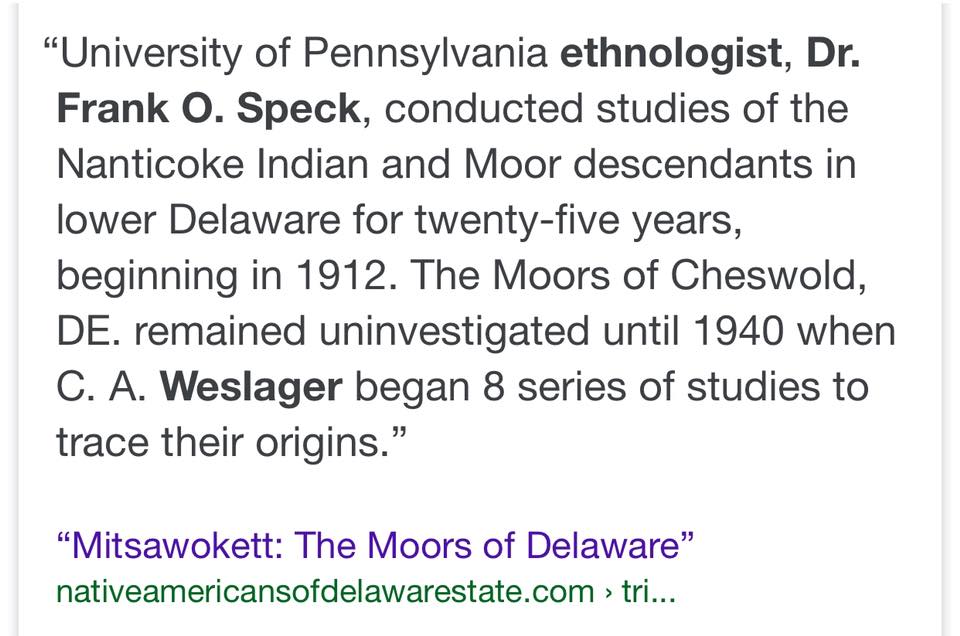

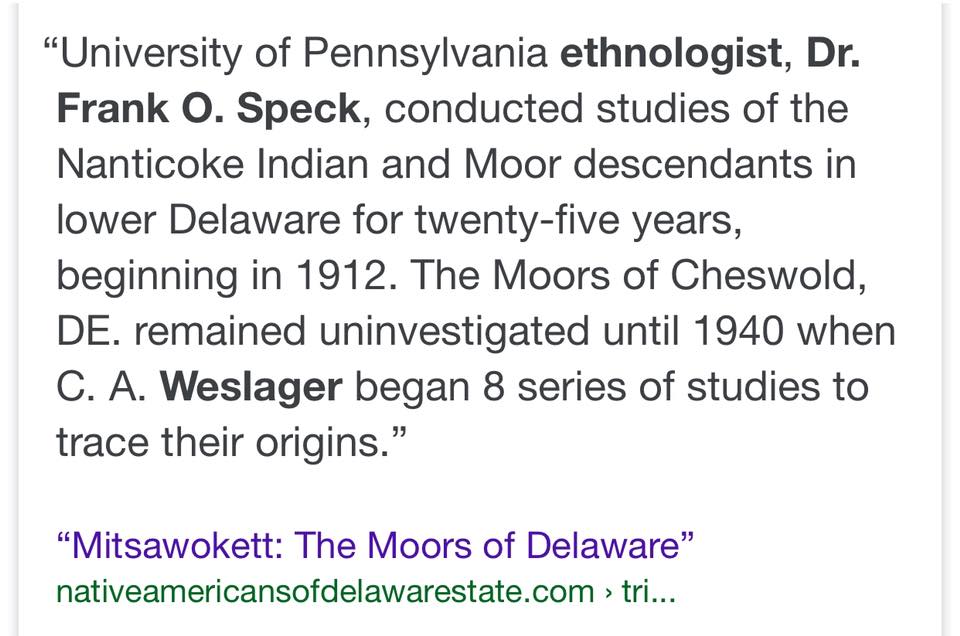

5. The earliest study was made in 1898 when anthropologist William Babcock from Washington, D. C. visited Indian River Hundred and published an article in the 1899 issue of The American Anthropologist. University of Pennsylvania ethnologist, Dr. Frank O. Speck, conducted studies of the Nanticoke Indian and Moor descendants in lower Delaware for twenty-five years, beginning in 1912. The Moors of Cheswold, DE. remained uninvestigated until 1940 when C. A. Weslager began 8 series of studies to trace their origins.

6. C. A. Weslager, in Delaware: A History of the First State, edit. by H. Clay Reed, (New York, 1947), Vol. II, p. 610.

7. C. A. Weslager, Delaware’s Forgotten Folk, (Phila., 1943), pp. 25-39. Weslager states that the origin legends of the Moors were related to him chiefly by members of the Harmon, Wright, Mosley, Ridgeway, Kimmey and Norwood families.

8. See B. Fernow, (edit.), Documents Relating to the History of the Dutch and Swedish Settlements on the Delaware, (1877).

9. C. H. B. Turner, (edit.), Some Records of Sussex County, (Phila., 1909), p. 48.

10. C. A. Weslager, Delaware’s Forgotten Folk, p. 28o

11. Donald VanLear Downs, The Moors of Delaware, (Downs Chapel, DE., Aug. 10, 1060), pages unnumbered.

12. There are exceptions to this generalization. As mentioned previously, some of the Moors are now related to Nanticoke Indian descendants. Also, some Moors have left their communities, marrying whites, and have been assimilated into white communities. Fewer Moors have married blocks, as this is strongly discouraged.

13. The Cheswold Moor family names which Mrs. Carney listed include: Carney, Carter, Coker, Davis, Dean, Drain, Durham, Greenage, Hughes, Johnson, Morgan, Morris, Mosley, Pritchett, Reed, Sammons, Seeney, and Wilson

14. C. A. Weslager, in Delaware: A History of the First State, H. Clay Reed, edit., Vol II, p. 611.

15. Ibid.

16. Downs, The Moors of Delaware, pages unnumbered.

17. The week of May 22-May 29, 1974 was spent in Delaware; fieldwork was interspersed with library research and consisted of:

May 28, 1974–Untaped interview with Mrs. Dorothy W. D. Carney and her daughter, (Donna) Colette Carney, Dover, DE.

May 24, 1974–Untaped interview with Wilson Seville Davis, Greenville, DE.

May 25, 1974–Visited Cheswold, DE. where attended Sunday morning service at the

Immanuel Methodist Church; casual conversations held with the minister, Rev. John W. Van Tine, and some members of the congregations; photographic “notes” taken of the town of Cheswold and the surrounding area.

18. Neither Mrs. Carney nor Wilson Davis know why the “Big Thursday” celebration was held on the second Thursday in August and they did not feel that the Moors’ “Big Thursday” celebrations which were held at Slaughter Beach, DE when the summer crabbing and oystering bans were lifted. (Note–this is exactly the sentence written. It is not complete.)

References

Books and articles:

Berry, Brewton, Almost White, New York: The MacMillan Co., 1963.

Bush, W.G., “Big Thursday.” Delaware Folklore Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 5, (March, 1955), p.18.

Conrad, Henry C., History of the State of Delaware from the Earliest Settlements to the Year 1907, Vol. 2. Wilmington, DE.: Published by the author.

DeValinger, Leon, Jr., Reconstructed 1790 Census of Delaware, Genealogical Publications of the National Genealogical Society, No. 10, (Jan., 1954), Wash., D.C.: National Genealogical Society.

Downs, Donald VanLear, The Moors of Delaware, (unpublished mimeograph), Downs Chapel, Delaware: dated Aug. 10, 1960.

Dunlap, A.R., and C.A. Weslager, “Trends in the Naming of Tri-Racial, Mixed-Blood Groups in the Eastern United States” American Speech, Vol. No. 2. (April, 1947), pp. 81-87.

Federal Writers’ Project, Delaware: A Guide to the First State, American Guide Series, New York: Hastings House, 1955.

Federal Writers’ Project, New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past, New York: Viking Press, 1939.

Fernow, B. (edit.), Documents Relating to the History of the Dutch and Swedish Settlements on the Delaware, Albany, 1877.

Fisher, George P., The So-Called Moors of Delaware, (lst pub, in Milford, DE Herald, June 15, 1895), Dover, DE.: The Public Archives Commission of Delaware, 1929.

Fitzgerald, Neil, “Delaware’s Forgotten Minority: The Moors,” Delaware Today Magazine, Vol. 10, No. 1, (Jan., 1972), pp. 10-13 ++.

Gilbert, William Harlen, Jr., “Memorandum Concerning the Characteristics of the Larger Mixed-Blood Racial Islands of the Eastern United States,” Social Forces, Vol. 24, (1946), pp. 438-447.

Gorden, Milton M., “Assimilation in America: Theory and Reality” in Minorities in a Changing World” (Milton L. Barron edit.), New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1967, (Ch. 28, pp. 393-417).

Herskovits, Melville J., Cultural Dynamics, (abr. from Cultural Anthropology), New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964, (1947).

Johnson, Guy B., “Personality in a White-Indian-Negro Community.” American Sociological Review, Vol. 4, No. 4, (Aug., 1939), pp. 516- 523.

Price, Edward T., “A Geographic Analysis of White-Indian-Negro Racial Mixtures in the Eastern United States,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Vol. 43, No, 2, (June, 1953) pp. 138-155.

Reed, H. Clay, (edit.) with Marion B. Reed, Delaware: A History of the First State Vol. II, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1947.

Scharf, J. Thomas, History of Delaware, Vol. 2, Phila.: L.J. Richards and Co., 1888.

Turner, C.H.B., (edit.), Some Records of Sussex County, Philadelphia, 1909.

Weslager, C.A., Delaware’s Forgotten Folk: the Story of the Moors and Nanticokes, Phila.: Univ. of Penn. Press, 1943.

Weslager, C.A., “Folklore Among the Nanticokes of Indian River Hundred and the Moors of Cheswold, Delaware,” Delaware Folklore Bulletin,, Vol. 1, No. 5, (March, 1955), pp. 17-18.

Newspaper Articles:

Bey, Omar Kane, “American Moors,” “Letters to the Editor,” Evening Journal, Wilmington, DE, Feb. 20, 1972, p. 22.

Frank, William P., “New Book A Compendium of Old Indian Medicines,” Evening Journal, Wilmington, DE, Jan. 10, 1974, p. 30.

“Moors are Just Americans,” “Letters to the Editor,” Evening Journal, Wilmington, DE., Feb. 11, 1972, p. 22.

“The Moors and Busing,” “Editorials,” Morning News, Wilmington, DE, Nov. 18 1971, p. 40.

Interviews:

Dorothy W.D. Carney and her daughter, (Donna) Colette Carney, Dover, DE, May 28, 1974.

Wilson Seville Davis, Greenville, DE, May 24, 1974.