By D. L. Birchfield

Overview

The Siouan-language peoples comprise one of the largest language groups north of Mexico, second only to the Algonquian family of languages. Many Siouan-language peoples are no longer identified as Sioux, but have evolved their own separate tribal identities centuries ago, long before contact with non-Indians. The name Sioux originates from a French version of the Chippewa Nadouessioux (snakes). The immense geographical spread of Siouan-language peoples, from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, attests to their importance in the history of the North American continent—most of that history having occurred before the arrival of non-Indians. Those known today as Sioux (the Dakota, the Lakota, and the Nakota), living primarily in the upper Great Plains region, are among the best-known Indians within American popular culture due to their participation in what Americans perceive to have been dramatic events within their own history, such as the Battle of the Little Big Horn in the late nineteenth century. American students have been told for more than a century that there were no survivors, despite the fact that approximately 2,500 Indian participants survived the battle. The lands of the Sioux have also been a focal point for some of the most dramatic events in the American Indian Movement of recent times, especially the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973, which brought national media attention to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Sioux writers, poets, and political leaders are today among the most influential leaders in the North American Native American community of nations, and the Sioux religion can be found to have an influence far beyond the Sioux people.

HISTORY

The Sioux had the misfortune of becoming intimately acquainted with the westward thrust of American expansion at a time when American attitudes toward Indians had grown cynical. In the East and Southeast, from early colonial times, there was much disagreement regarding the nature of the relations with the Indian nations. There was also a constant need to have allies among the Indian nations during the period of European colonial rivalry on the North American continent, a need that the newly formed United States felt with great urgency during the first generation of its existence. After the War of 1812, things changed rapidly in the East and Southeast. Indians as allies became much less necessary. It was the discovery of gold in 1828, however, at the far southern end of the Cherokee Nation near the border with Georgia that set off a Southern gold rush and brought an urgency to long-debated questions of what the nature of relations with the Indian nations should be.

Greed for gold would play a pivotal role in the undermining of Sioux national independence. At mid-century streams of men from the East first passed through Sioux lands on their way to the gold fields of California. They brought with them smallpox, measles, and other contagious diseases for which the Sioux had no immunity, and which ravaged their population by an estimated one-half. Later, in the 1870s, the discovery of gold in the heart of Paha Sapa (the Black Hills), the sacred land of the Sioux, brought hordes of miners and the U.S. Army, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, into the center of their sacred “heart of everything that is” in a blatant violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868.

The Sioux had no way of knowing about the process that had worked itself out in the East and Southeast, whereby, in direct contravention of a U.S. Supreme Court decision (Worchester vs. Georgia ), Indians would no longer be dealt with as sovereign nations. No longer needed as allies, and looked upon as merely being in the way, Indians entered a perilous time of being regarded as dependent domestic minorities. Many Eastern and Southern Indian nations were uprooted and forced to remove themselves beyond the Mississippi River. By the time American expansion reached Texas, attitudes had hardened to a point at which Texans systematically expelled or exterminated nearly all of the Indians within their borders; however, Sam Houston, during his terms as president of the republic of Texas and as governor of the state of Texas, unsuccessfully attempted to accommodate the needs of Indians into Texas governmental policy.

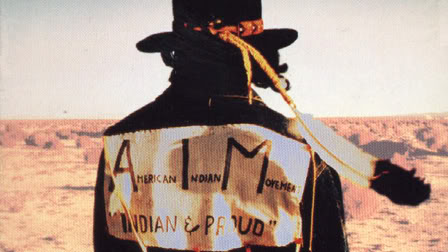

To the Sioux in the second half of the nineteenth century, the U.S. government was duplicitous, greedy, corrupt, and without conscience. The Sioux watched the great buffalo herds be deliberately exterminated by U.S. Army policy; and within a generation they found themselves paupers in their native land, with no alternative but to accept reservation life. They found it impossible to maintain honorable, peaceful relations with the United States. At first, attempts were made to acculturate the Sioux, to assimilate them out of existence as a separate people; then in the mid-twentieth century, the government attempted to legislate them out of existence through an official policy of “termination” of Indian nations. Only within recent decades have there been attempts on the part of the U.S. government to redress past wrongs. In the 1960s, under the occasional prod of court decisions and a national consciousness focused on civil rights legislation for minorities, attempts were made to recognize and respect significant remaining vestiges of Indian sovereignty. Finally, by legislation in 1979 Indians were allowed to openly practice their religions without threat of criminal prosecution. The gains have not come without bloodshed and strife, however, especially in the lands of the Sioux and especially during the mid-1970s—a time of virtual civil war on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Alarmed by the bold actions and the extent of the demands by some groups of Indians, particularly the American Indian Movement (AIM), the U.S. government tried to slow the pace of change by exploiting differences between the more acculturated Indians and the more traditional Indians. Since that time, much healing has occurred; but the question of what the nature of the relations between the Native peoples of this continent and the people of the United States will be remains open.

MODERN ERA

Federally recognized contemporary Sioux tribal governments are located in Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana. According to the 1990 census, South Dakota ranked eleventh among all states for the number of Indians represented in its population (50,575, which was 7.3 percent of the South Dakota population, up from 6.5 percent in 1980). Minnesota ranked twelfth with a reported total of 49,909 Indians, or 1.1 percent of its population (up from 0.9 percent in 1980). Montana ranked thirteenth with a reported total of 47,679 Indians, or 6.0 percent of its population (up from 4.7 percent in 1980). North Dakota ranked eighteenth with a reported total of 25,917 Indians, or 4.1 percent of its population (up from 3.1 percent in 1980). Nebraska ranked thirty-fifth with a reported total of 12,410 Indians, or 0.8 percent of its population (up from 0.6 percent in 1980).

Many Native Americans from these areas have migrated to urban industrial centers throughout the continent. Contemporary estimates are that at least 50 percent of the Indian population in the United States now resides in urban areas, frequently within the region of the tribal homeland but often at great distances from it. Other populations of Sioux are to be found in the prairie provinces of Canada.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Beginning in the late nineteenth century the U.S. government attempted to force the Sioux to assimilate into American culture. The prime weapon of cultural genocide as practiced by the United States was a school system contracted to missionaries who had little regard for traditional Sioux culture, language, or beliefs. Sioux children, isolated from their families, were punished if they were caught speaking their native tongue. Their hair was cropped, and school and dormitory life was conducted on a military model. Many children attended the school located at Flandreau, South Dakota. Some Sioux children were removed to schools in the East, to Hampton Institute in Virginia, or to the Indian school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, while others attended the Santa Fe Indian School and the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas. Throughout this ordeal, the Sioux were able to retain their language and religion, while learning English and adjusting to the demands of American culture. Some Sioux began attaining distinction early in this process, such as physician Charles Eastman. Today, the Sioux people are at home in both worlds. Sioux intellectuals and academicians, such as noted author Vine Deloria Jr., and poet and scholar Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, who also edits Wicazo Sa Review, a scholarly journal for Native American Studies professionals, are leaders within their respective fields within the North American Native American community.

TRADITIONAL CRAFTS

The Sioux are skilled artisans at beadwork, quill-work, carving, pipe making, drum making, flute making, and leatherwork of all kinds—from competition powwow regalia to saddles and tack. These are crafts that have been handed down from generation to generation. Intertribal powwow competitions, festivals, and tribal fairs bring forth impressive displays of Sioux traditional crafts. A large tribal arts and crafts fair is held annually at New Town, North Dakota, September 17-19.

DANCES AND SONGS

Summer is the most popular season for powwows. Intertribal powwows featuring dance competitions are the ones at which visitors are most welcome. A number of powwows tend to occur annually on the same date. Powwows are held at a number of communities in South Dakota on May 7, including the communities of Wounded Knee, Kyle, Oglala, Allen, and Porcupine. A Memorial Day weekend powwow is held by the Devil’s Lake Sioux at Fort Totten, North Dakota. Powwows are held in mid-June at Fort Yates, North Dakota, and at Grass Mountain, South Dakota. Powwows are held July 2-4 at La Creek, South Dakota; July 2-5 at Cannon Ball, North Dakota; July 3-5 at Spring Creek, South Dakota, at Greenwood, South Dakota, and at Fort Thompson, North Dakota; July 14-16 at Mission South Dakota; July 15-16 at Flandreau, South Dakota; July 17-19 at New Town, North Dakota; July 21-23 at Cherry Creek, South Dakota; July 28-30 at Little Eagle, South Dakota; and the last weekend of July at Belcourt, North Dakota. August and September are also popular months, with powwows held at Lake Andes, South Dakota, each weekend during the first half of August; at Fort Yates, North Dakota, August 4-6; at Rosebud, South Dakota, August 11-13; at Bull Head, North Dakota, August 13-15; at Bull Creek and Soldier Creek, South Dakota, September 2-4; and at Sisseton, South Dakota, and Fort Totten, North Dakota, over the Labor Day holiday.

HOLIDAYS

The Spotted Tail Memorial Celebration is held in late June at Rosebud, South Dakota. July 1-4 is the date of the Sioux Ceremonial at Sisseton, South Dakota. The Sioux Coronation is held in early October at Fort Totten, North Dakota. Tribal fairs are held July 23-25 at Fort Totten, North Dakota; August 7-9 at Lower Brule, South Dakota; August 21-23 at Rosebud, South Dakota; August 27-29 at Eagle Butte, South Dakota; and Labor Day weekend at Devils Lake and Fort Totten, North Dakota.

HEALTH ISSUES

All of the health problems associated with poverty in the United States can be found among the contemporary Sioux people. Alcoholism has proven to be especially debilitating. Many traditional Indian movements, including AIM, have worked toward regaining pride in Native culture, including efforts to combat alcohol abuse and the toll that it takes among contemporary Native peoples.

Language

The Iroquoian language family, the Caddoan language family, the Yuchi language family, and the Siouan language family all belong to the Macro-Siouan language phylum, indicating a probable divergence in the distant past from a common ancestor language. Geographically, the Iroquoian family of languages (Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Mohawk, Oneida, and Wyandot—also known as Huron), are found in the Northeast, primarily in New York state and the adjacent areas of Canada, and in the Southeast (Tuscarora, originally in North Carolina, later in New York; and Cherokee, in the Southern Appalachians, and later in Oklahoma). The Caddoan language family includes the Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara languages, which are found on the central Plains. Yuchi is a language isolate of the Southern Appalachians.

Members of the Siouan language family proper are to be found practically everywhere east of the Rocky Mountains except on the southern Plains and in the Northeast. On the northern Plains are found the Crow, Hidatsa, and Dakota (also known as Sioux) languages. On the central Plains are found the Omaha, Osage, Ponca, Kansa, and Quapaw languages; in Wisconsin one finds the Winnebago language; on the Gulf Coast are the Tutelo, Ofo, and Biloxi languages; and in the Southeast one finds Catawba. The immense geographical spread of the languages within this family is testimony to the importance of Siouan-speaking peoples in the history of the continent. They have been a people on the move for a very long time.

Oral traditions among some of the Siouan-speaking peoples document the approximate point of divergence for the development of a separate tribal identity and, eventually, the evolution of a separate language unintelligible to their former kinspeople. Siouan-speaking peoples of all contemporary tribal identities, however, share creation stories accounting for their origin as a people. They come from the stars, which can be contrasted, for example, with the Macro-Algonkian phylum, Muskogean-speaking Choctaws who emerged from a hole in the earth near the sacred mother mound, Nanih Waiya. It can be contrasted also with the Aztec-Tanoan phylum, Uto-Aztecan-speaking Hopi, who believe they have ascended upward through successive layers of worlds to the one they presently occupy.

Siouan-speaking peoples also exhibit a reverence for the number seven, whereas Choctaws hold that the sacred number is four. There are fundamental cultural differences between Native American peoples whom Europeans and Americans have considered more similar than different. For example, the Macro-Siouan phylum, Iroquoian-speaking Cherokees and the Macro-Algonkian phylum, Muskogean-speaking Choctaws have both been categorized by non-Indians as members of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” due to similarities in their material culture; whereas knowledgeable Choctaws consider the Cherokees to have about three too many sacred numbers.

Today the Sioux language consists of three principal, mutually intelligible dialects: Dakota (Santee), Lakota (Teton), and Nakota (Yankton). The Sioux language is not restricted to the United States but also extends far into the prairie provinces of Canada. The Sioux were also masters of sign language, an ancient vehicle of communication among peoples who are native to the North American continent. The Sioux language can be heard in a video documentary (Wiping The Tears of Seven Generations, directed by Gary Rhine and Fidel Moreno, Kafaru Productions, 1992), which records interviews with a number of Sioux members of the Wounded Knee Survivors’ Association, as they relate what their grandparents told them about the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee.

Family and Community Dynamics

The basic unit of traditional Sioux family and community life is the tiyospaye, a small group of related families. In the era of the buffalo, the tiyospaye was a highly mobile unit capable of daily movement if necessary. A tiyospaye might include 30 or more households. From these related households a headman achieved the position of leadership by demonstrating characteristics valued by the group, such as generosity, wisdom, fortitude, and spiritual power gained through dreams and visions. Acculturation, assimilation, and intermarriage have made inroads into Sioux traditional family and community relationships. The more isolated and rural portions of the population tend to be more traditional.

In traditional Lakota community life, fraternal societies, called akicitas, are significant within the life of the group. During the era of the buffalo when Lakota society was highly mobile, fraternal societies helped young men develop leadership skills by assigning them roles in maintaining orderly camp movements. Membership was by invitation only and restricted to the most promising young men. Another kind of fraternity, the nacas, was composed of older men with proven abilities. The most important of the nacas societies, the Naca Omincia, functioned as something of a tribal council. Operating by consensus, it had the power to declare war and to negotiate peace. A few members of the Naca Ominicia were appointed wicasa itancans, who were responsible for implementing decisions of the Naca Ominicia. Many vestiges of traditional Lakota community organizational structure have been replaced, at least on the surface, by structures forced upon the Lakota by the U.S. government. One important leader in the society was the wicasa wakan, a healer respected for wisdom as well as curative powers. This healer was consulted on important tribal decisions by the wicasa itancans, and is still consulted on important matters by the Lakota people today.

Religion

The Sun Dance, also known as the Offerings Lodge ceremonial, is one of the seven sacred ceremonials of the Sioux and is a ceremonial for which they have come to be widely known. The most famous Sun Dance occurs in early August at Pine Ridge. The Sun Dance takes place in early July at Rosebud, and at other times among other Sioux communities. The ceremonials, however, are not performed for the benefit of tourists. Attendance by tourists is discouraged.

No American Indian religion has been more closely studied or more widely known than the Sioux religion, partly due to the appeal of John Niehardt’s book, Black Elk Speaks, in which he recorded his interviews with the Sioux spiritual leader earlier this century. Another reason for its prominence is because the American Indian Movement adopted many of the practices of the Sioux religion for its own and carried those practices to many areas of the continent where they had not been widely known. The so-called New Age movement within American culture has also become captivated by the religious practices of the northern Plains Indians, primarily the Cheyenne and the Sioux (practices that are largely foreign to Indians in many other areas of the continent, but which are perceived by many Americans as representative of Indians in general). Yet, until by act of Congress, the American Indians Religious Freedom Act of 1978, the practice of Indian religions was a crime in the United States.

The practice of many Native American religions throughout the continent was forced underground in the late nineteenth century as news spread about the massacre of 153 unarmed Minneconjou Sioux men, women, and children by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation on December 29, 1890. The Minneconjous, camped at Wounded Knee Creek, had been holding a Ghost Dance, attempting to fulfill the prophecies of the Paiute visionary Wovoka. While fleeing their own agency after the murder of Sitting Bull, they tried to reach what they perceived to be the safety of the protection of Chief Red Cloud at Pine Ridge, who was on friendly terms with the U.S. government.

Perhaps because the massacre at Wounded Knee was one of Sioux people on Sioux land, the Sioux have been strong contemporary leaders in asserting the religious rights of Native peoples. These efforts have also been vigorously pursued on behalf of incarcerated Native Americans, where penal authorities in practically every state historically have been contemptuous of the religious rights of Native American inmates.

While the ceremonials of the Sioux, the Sun Dance, the Sweat Lodge, and other aspects of their religion may be foreign to many other Native Americans (for example, the sweat lodge, a religious ceremonial among the Sioux, is merely a fraternal and communal event among the Choctaws and many other Native peoples), one aspect of the Sioux religion is nearly universal among North America‘s Indians—the sanctity of land and the reverence for particular sacred lands. For the Sioux and for the Cheyenne, the sacred land is Paha Sapa, known in American culture as the Black Hills, and their major contemporary struggle is to regain it. They have won a decision from the U.S. Indian Claims Commission that Paha Sapa was taken from them illegally by the United States, and that they are entitled to $122 million in compensation. The Sioux have rejected the award of money, which, being held in trust for them, has now accumulated interest to a total of more than $400 million. They are not interested in money; they want Paha Sapa; and there is precedent for their demand. In 1970 Congress passed, and President Richard Nixon signed, legislation returning Blue Lake—the sacred lake of Taos Pueblo—and 48,000 surrounding acres to Taos Pueblo. This was the first return of land to Indians for religious purposes by the United States.

Employment and Economic Traditions

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the U.S. government tried to force the Sioux to become farmers. Cattle ranching, however, has become more important to them and many Sioux derive some economic benefit from the cattle industry. Sioux have distinguished themselves on the professional rodeo and all-Indian rodeo circuits.

Sioux reservations are isolated from urban industrial centers, have attracted very little industry, and experience some of the highest levels of unemployment and the highest levels of poverty of any communities within the United States. For example, on the Cheyenne River Reservation in the mid-1980s, unemployment averaged roughly 80 percent and 65 percent of all families were living on less than $3,000 per year. Many Sioux have found it necessary to leave their communities to find employment. Like many Indian reservations, various agencies of the U.S. government and programs funded by the government account for the largest percentage of jobs. Extractive industries also provide some employment, but the economic benefits go largely to non-Indians, and many traditional Sioux refuse to participate in economic activities that scar and pollute their land. The discovery of uranium on Sioux lands, which has raised questions regarding if and how it should be extracted, has been a divisive issue within Sioux communities.

Politics and Government

The structure and operation of the contemporary government of the Lakota tribal division of the Sioux serves as an example of that of other Sioux governments. The contemporary national government of the Lakota nation is the National Sioux Council, which is composed of delegates from the Lakota reservations at Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, Lower Brule, Crow Creek, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Santee, and Fort Peck. The council meets annually to discuss matters affecting the entire Lakota nation. It is based on the traditional model of Lakota government, where the headman of each band represented the band’s tribe, and the headman of each Lakota tribe represented the Greater Sioux Council. Essentially a federal structure, it also functions by the imposition of vote counting rather than consensus—a quintessential American Indian method of decision making.

Each contemporary Lakota reservation is governed by an elected tribal council. The organization of the Cheyenne River Reservation tribal council, for example, is a supreme governing body for the Cheyenne River Sioux. It is empowered to enter into negotiations with foreign governments, such as the government of the United States, to pass laws and establish courts, appoint tribal officials, and administer the tribal budget. Certain kinds of actions by the tribal council, however, are subject to the authority of the secretary of the interior of the U.S. government, a reminder that the Sioux are not alone in their land. The council consists of 18 members, 15 of which are elected from six voting districts (the districts being apportioned according to population), and three who are elected at large—the chairperson, the secretary, and the treasurer. The council elects a vice-chairperson from among its members. Each tribal council member reports to the district tribal council for the district from which the council member was elected. These district councils are locally elected.

To vote or hold office at Cheyenne River one must be an enrolled tribal member and meet residency requirements. For enrollment, one must be one-quarter blood or more Cheyenne River Sioux and one’s parents must also have been residents of the reservation. However, a two-thirds vote of the tribal council may enroll a person of Cheyenne River Indian blood who does not meet either the blood quantum or the parental residency requirements. To vote, one must meet a 30-day residency requirement; to hold office, the residency requirement is one year.

THE “INCIDENT AT OGLALA”

No other event typifies the problems encountered by traditional Indians in seeking the redress of long-standing grievances with the United States more than the 71-day siege of Wounded Knee in 1973, known as the “Incident at Oglala.” When the siege ended in May of 1973, and when no network correspondents remained to tell the world what was happening on the Pine Ridge Reservation, traditional Indians and supporters of the American Indian Movement (AIM) endured a reign of terror that lasted for more than two years. Frightened by the takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C., and by the occupation of Wounded Knee, the mixed-blood leadership of the Oglala Lakota tribal government moved to crush political activism on the reservation while the AIM leadership was in court. Federal authorities allowed and funded heavily armed vigilantes, called goon squads (Guardians of the Oglala Nation), who patrolled the roads and created a police state. Freedom of assembly, freedom of association, and freedom of speech ceased to exist. Violence reigned. Drive-by shootings, cars run off the road, firebombings and murders became the norm.

During one 12-month period there were more murders on the Pine Ridge Reservation than in all the other parts of South Dakota combined. The reservation had the highest per capita murder rate in the United States. By June of 1975 there had been more than 60 unsolved murders of traditional Indians and AIM supporters. The FBI, charged with solving crimes on Indian reservations, took little interest in the killings. But when two FBI agents were killed near the community of Oglala on the Pine Ridge Reservation on June 26, 1975, 350 FBI agents were on the scene within three days.

Two FBI agents, new to the area and unknown to its residents, were dressed in plain clothes and driving unmarked cars; they reported that they were following a red pickup truck, which they believed contained a man who was wanted for stealing a pair of boots. The vehicle actually contained a load of explosives destined for an encampment of about a dozen members of the AIM, not far from the community of Oglala. When the two FBI agents followed the red pickup off the road and into a field, to a point within earshot of the encampment, a firefight erupted between the two FBI agents and the occupants of the vehicle, who have never been identified. Armed only with their handguns, the agents attempted to get their rifles out of the trunks of their cars, and in so doing exposed themselves to the gunfire. Hearing the shooting, and thinking themselves under attack, men and women from the encampment came running, carrying rifles. They took up positions on a ridge overlooking the vehicles; when fired at, they returned the fire. Within a few minutes a third FBI agent arrived but not before the first two FBI agents lay dead near their vehicles. The red pickup fled the scene, but it had been seen and reported, and the report preserved in the records of FBI radio transmissions. The AIM members on the ridge from the encampment, went down to the vehicles and discovered the bodies of the two FBI agents. Bewildered and frightened, they fled the area on foot, under heavy fire, as law enforcement authorities began arriving en masse, but not before an Indian man lay dead—shot through the head at long range. The two FBI agents, already wounded, had been shot through the head at point blank range.

The full fury of the FBI descended on Pine Ridge Reservation. The director of the FBI appeared on television and announced a nationwide search for the red pickup. In the months that followed, the FBI was unable to find the red pickup or its occupants. Three men who had been at the AIM encampment that day, Darrelle Butler, Bob Robideau, and Leonard Peltier, were arrested and charged with killing the two FBI agents. No one was ever charged with killing the Indian. Peltier, in Canada, fought extradition. Butler and Robideau, however, were tried and acquitted by a jury that believed they had acted in self-defense and that they had not been the ones who executed the wounded agents. The fury of the government then fell on the third defendant, Leonard Peltier. The United States presented coerced, perjured documents to the Canadian authorities to secure Peltier’s extradition from Canada. At the trial, the red pickup truck now became a red and white van, like the one to which Leonard Peltier could be linked. FBI agents who had filed reports the day of the shooting, reporting the red pickup, now testified differently, saying their reports had been in error. The government now claimed that the two dead FBI agents who had reported that they were following a red pickup did not know the difference between a red pickup and a red and white van.

With the first trial as a blueprint for everything it had done wrong in the courtroom, the government found a sympathetic judge in another jurisdiction who ruled favorably for the prosecution, and against the defense, disallowing testimony about the climate of violence and fear on the reservation, and effectively thwarting the defense of self-defense. Also, by withholding the results of crucial FBI ballistics tests, which showed that Leonard Peltier’s weapon had not fired the fatal shots, the government got a conviction against Peltier. He was sentenced to two life terms in the federal penitentiary. A recent documentary (Incident At Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story ), through interviews with numerous participants, examines in detail the events of the day the two FBI agents were killed, and the government case against Peltier, revealing that in a fair trial Peltier would have been acquitted, as Butler and Robideau were, and that the nature of his involvement was the same as theirs.

Individual and Group Contributions

ACADEMIA

Sioux author, professor, and attorney Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933– ), has been one of the most articulate speakers for the recognition of Indian political and religious rights. Born at Standing Rock on the Pine Ridge Reservation, he holds degrees in divinity from the Lutheran School of Theology and in law from the University of Colorado. His writings include Custer Died For Your Sins (1969), We Talk, You Listen: New Tribes, New Turf (1970).

LITERATURE

Sioux poet, author, and professor Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (1930– ), born on the Crow Creek Reservation, is a granddaughter of Gabriel Renville, a linguist who helped develop Dakota dictionaries; a Dakota speaker herself, Cook-Lynn has gained prominence as a professor, editor, poet, and scholar; she is emeritus professor of American and Indian studies at Eastern Washington State University, and in 1985 she became a founding editor of Wicazo Sa Review, a bi-annual scholarly journal for Native American studies professionals; her book of poetry, Then Badger Said This, and her short fiction in journals have established her as a leader among American Indian creative voices. Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, a Rosebud Sioux, is the author of eight children’s books and other works of historical nonfiction for adults; in 1992 she won the Native American Prose Award from the University of Nebraska Press for her book Closing The Circle. Oglala Sioux Robert L. Perea (1944– ), born in Wheatland, Wyoming, is also half Chicano; a graduate of the University of New Mexico, he has published short stories in anthologies such as Mestizo: An Anthology of Chicano Literature and The Remembered Earth; in 1992 Perea won the inaugural Louis Littlecoon Oliver Memorial Prose Award from his fellow creative writers and poets in the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas for his short story, “Stacey’s Story.” Philip H. Red-Eagle, Jr., a Wahpeton-Sisseton Sioux, is a founding editor of The Raven Chronicles, a multi-cultural journal of literature and the arts in Seattle; in 1993, Red-Eagle won the Louis Littlecoon Oliver Memorial Prose Award for his manuscript novel, Red Earth, which is drawn from his experiences in the Viet Nam War. Fellow Seattle resident and Sioux poet, Tiffany Midge, who is also enrolled at Standing Rock, captured the 1994 Diane Decorah Memorial Poetry Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas for her book-length poetry manuscript, Diary of a Mixed-Up Half-Breed. Susan Power, who is enrolled at Standing Rock, gained national attention with the 1994 publication of her first novel, The Grass Dancer.

VISUAL ARTS

Yankton Sioux graphic artist Oscar Howe (1915-1984) has become one of the best known Native American artists in the United States. Known as Mazuha Koshina (trader boy), Howe was born at Joe Creek on the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota. He earned degrees from Dakota Wesleyan University and the University of Oklahoma, and was a professor of fine arts and artist in residence at the University of South Dakota for 15 years. His work is characterized by poignant images of Indian culture in transition and is depicted in a modern style.

Media

Lakota Times.

Address: 1920 Lombardy Drive, Rapid City, South Dakota 57701.

Oglala Nation News.

Address: Pine Ridge, South Dakota 57770.

Paha Sapa Wahosi.

Address: South Dakota State College, Spearfish, South Dakota 57783.

Rosebud Sioux Herald.

Address: P.O. Box 65, Rosebud, South Dakota 57570.

Sioux Journal.

Address: Eagle Butte, South Dakota 57625.

Sisseton Agency News.

Address: Sisseton BIA Agency, Sisseton, South Dakota 57262.

Standing Rock Star.

Address: Box 202, Bullhead, South Dakota 57621.

Three Tribes Herald.

Address: Parshall, North Dakota 58770.

Wicazo Sa Review.

Address: Route 8, Box 510, Rapid City, South Dakota 57702.

Wotanin-Wowapi.

Newspaper of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes.

Contact: Bonnie Red Elk, Editor.

Address: Box 1027, Poplar, Montana 59255.

Telephone: (406) 768-5155.

Fax: (406) 768-5478.

RADIO

KCCR-AM (1240).

Address: 106 West Capitol, Pierre, South Dakota 57501.

KEYA-FM (88.5).

Address: P.O. Box 190, Belcourt, North Dakota 58316.

Telephone: (701) 477-5686.

Fax: (701) 477-3252.

KILI-FM (90.1).

Address: P.O. Box 150, Porcupine, South Dakota 57772.

Telephone: (605) 867-5002.

Fax: (605) 867-5634.

KINI-FM (96.1).

Address: P.O. Box 149, St. Francis, South Dakota 57572.

Telephone: (605) 747-2291.

Fax: (605) 747-5791.

KLND-FM (89.5).

Address: P.O. Box 32, Little Eagle, South Dakota 57639.

Telephone: (605) 823-4663.

Organizations and Associations

Cheyenne River Sioux.

Sioux tribal divisions represented on this reservation include the Sihasapa, Minneconjou, Sans Arcs, and the Oohenonpa.

Contact: Gregg J. Bourland, Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box 590, Eagle Butte, South Dakota 57625.

Telephone: (605) 964-4155.

Fax: (605) 964-4151.

Crow Creek Sioux.

The Sioux on this reservation include descendants of a number of Sioux tribal divisions, including the Minneconjou, Oohenonpa, Lower Brule, and Lower Yanktonai.

Contact: Harold “Curly” Miller, Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box 50, Fort Thompson, South Dakota 57339.

Telephone: (605) 245-2221.

Fax: (605) 245-2470.

Devils Lake Sioux.

The Sioux on this reservation include Assiniboine, Pabaksa, Santee, Sisseton, Yanktonai, and Wahpeton Sioux.

Address: Sioux Community Center, Fort Totten, North Dakota 58335.

Telephone: (701) 766-4221.

Fax: (701) 766-4854.

Flandreau Santee Sioux.

Represented are descendants of the Santee Sioux who separated from the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Sioux in 1870 and settled at Flandreau in 1876.

Contact: Thomas Ranfranz, President.

Address: Flandreau Field Office, Box 283, Flandreau, South Dakota 57028.

Telephone: (605) 997-3871.

Fax: (605) 997-3878.

Fort Belknap Sioux.

Represented are the Assiniboine-Sioux and Gros Ventre.

Address: P.O. Box 249, Harlem, Montana 59526.

Telephone: (406) 353-2205.

Fax: (406) 353-2797.

Fort Peck Assiniboine-Sioux.

Represented are the Assiniboine-Sioux, closely related to the Yanktonai.

Address: P.O. Box 1027, Poplar, Montana 59255.

Telephone: (406) 768-5155.

Fax: (406) 768-5478.

Indian Center.

Address: 5633 Regent Avenue North, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55440.

Indian Center.

Address: Box 288, Yankton, South Dakota 57078.

Indian Community Center.

Address: 2957 Farnum, Omaha, Nebraska 68131.

Indian Student Association.

Address: University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455.

Lower Brule Sioux.

Represented are the Lower Brule and Yanktonai Sioux.

Contact: Michael Jandreau, Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box 187, Lower Brule, South Dakota 57548.

Telephone: (605) 473-5561.

Fax: (605) 473-5605.

Lower Sioux.

Represented are the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute divisions of the Santee Sioux.

Address: Route 1, Box 308, Morton, Minnesota 56270.

Telephone: (507) 697-6185.

Fax: (507) 697-6110.

Oglala Sioux.

Represented are predominantly Oglala Sioux, also Brule Sioux and Northern Cheyenne.

Contact: Harold D. Salway, President.

Address: P.O. Box H, Pine Ridge, South Dakota 57770.

Telephone: (605) 867-5821.

Fax: (605) 867-5659.

Prairie Island Sioux.

Represented are the Mdewakanton division of the Santee Sioux.

Address: 5750 Sturgeon Lake Road, Welch, Minnesota 55089.

Telephone: (612) 385-2536.

Fax: (612) 388-1576.

Rosebud Sioux.

Represented are the Oglala, Oohenonpa, Minneconjou, Upper Brule, Waglukhe, and Wahzhazhe Sioux.

Contact: Norman G. Wilson, President.

Address: P.O. Box 430, Rosebud, South Dakota 57570.

Telephone: (605) 747-2381.

Fax: (605) 747-2243.

Santee Sioux.

Represented are the Santee Sioux, including Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sisseton, and Wahpeton.

Contact: Arthur “Butch” Denny, Chairman.

Address: Route 2, Niobrara, Nebraska 68760.

Telephone: (402) 857-2302.

Fax: (402) 857-2307.

Sioux Tribes of South Dakota Development Corporation.

Promotes employment opportunities for Native Americans; offers job training services.

Address: 919 Main Street, Suite 114, Rapid City, South Dakota 57701-2686.

Telephone: (605) 343-1100.

Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux.

Represented are the Sisseton Sioux.

Contact: Andrew J. Grey, Sr., Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box 509, Niobrara, Nebraska 68760.

Telephone: (605) 698-3911.

Fax: (605) 698-7908.

Skakopee Sioux.

Represented are the Mdewakanton division of the Santee Sioux.

Address: 2330 Sioux Trail, Prior Lake, Minnesota 55372.

Telephone: (612) 445-8900.

Fax: (612) 445-8906.

South Dakota Commission on Indian Affairs.

Address: Pierre, South Dakota 57501.

Standing Rock Sioux.

Represented are predominantly the Teton Sioux, including Hunkpapa and Sihasapa, but also including Lower and Upper Yanktonai.

Contact: Charles W. Murphy, Chairman.

Address: P.O. Box D, Fort Yates, North Dakota 58538.

Telephone: (701) 854-7202.

Fax: (701) 854-7299.

Upper Sioux Community.

Represented are predominantly the Sisseton and Wahpeton divisions of the Santee Sioux, but Devil’s Lake, Flandreau, and Yanktonai Sioux are also included.

Address: P.O. Box 147, Granite Falls, Minnesota 56241.

Telephone: (612) 564-2360.

Fax: (612) 564-3264.

Urban Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux.

Address: 1128 Fifth Street, N.E., Minneapolis, Minnesota 55418.

Yankton Sioux.

Represented are the Yanktonai Sioux tribal division.

Address: P.O. Box 248, Marty, South Dakota 57361.

Telephone: (605) 384-3804.

Fax: (605) 384-5687.

Museums and Research Centers

Museums that focus on the Sioux include: the Minnesota Historical Society Museum in St. Paul, Minnesota; the Plains Indian Museum in Browning, Montana; the Affiliated Tribes Museum in New Town, North Dakota; the Indian Arts Museum in Martin, South Dakota; the Land of the Sioux Museum in Mobridge, South Dakota; the Mari Sandoz Museum on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota; the Sioux Indian Museum in Rapid City, South Dakota; and the University of South Dakota Museum in Vermillion.

Sources for Additional Study

Incident At Oglala: The Leonard Peltier Story (video documentary), directed by Michael Apted, narrated by Robert Redford. Carolco International N.V. and Spanish Fork Motion Picture Company, 1991.

Lakota: Seeking the Great Spirit. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994.

Marquis, Arnold. A Guide to America’s Indians: Ceremonials, Reservations, and Museums. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974.

McClain, Gary (Eagle Walking Turtle). Indian America: A Traveler’s Companion, third edition. Santa Fe, New Mexico: John Muir Publications, 1993.

Native America: Portrait of the Peoples, edited by Duane Champagne, foreword by Dennis Banks. Detroit: Gale Research, 1994.

Neihardt, Hilda. Black Elk and Flaming Rainbow: Personal Memories of the Lakota Holy Man and John Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Neihardt, John. Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961.

O’Brien, Sharon. American Indian Tribal Governments (Civilization of the American Indian Series). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

Paha Sapa: The Struggle for the Black Hills (video documentary), directed by Mel Lawrence. HBO Studio Productions, 1993.

Ross, A.C. Mitakuye Oyasin [We Are All Related]. Denver, CO: Wicóni Wasté, 1997.

Wiping the Tears of Seven Generations (video documentary), directed by Gary Rhine and Fidel Moreno. Kifaru Productions, 1992.