Simply…

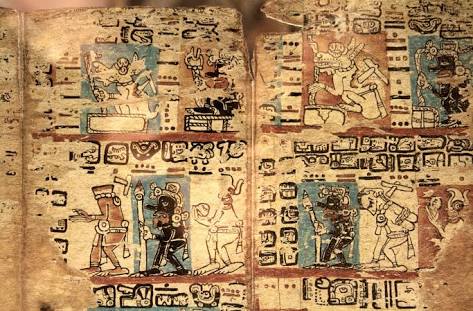

The first inhabitants of the Americas are thought to have crossed the Bering Straits from Asia around 50,000 BC. The earliest evidence of human life in central Mexico dates from about 20,000 BC, and the first signs of civilization appear in about 1,500 BC. Olmec cities were built in the jungles of the Gulf coast, and although little evidence of them remains the Olmecs were the first people in the Western hemisphere to work on hieroglyphic and numeric systems.

|

|

PEAKIn the Valley of Mexico Teotihuacán (a name later given to it by the Aztecs meaning ‘the place where people became gods’) became the first truly urban society in the Western hemisphere from about 300 AD. The huge pyramids of the Sun and Moon that remain today testify to an urban society ruled by a religious élite whose influence spread over a wide area. The gods Tlaloc (rain and fertility) and Quezalcoatl (the plumed serpent that brought civilization) made their first appearance. To the south the great Mayan centres in the lowlands of present-day Guatemala and Honduras reached their peak at about the same time and perfected an extraordinarily accurate calendar. But Teotihuacán was abandoned in mysterious circumstances around 750 AD, and the Mayan centres were also in decline by 800 AD. |

|

3

|

DECLINE |

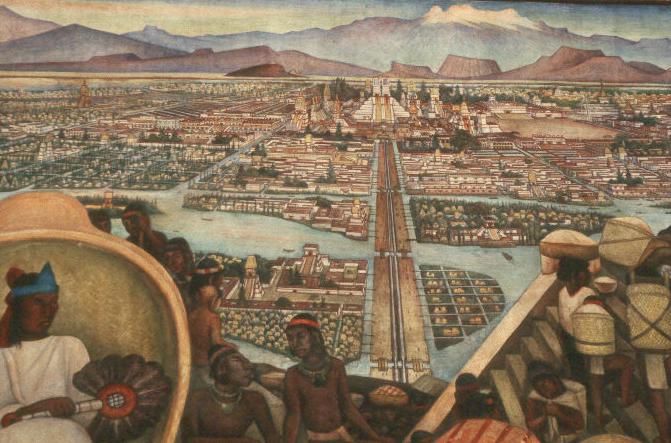

Wandering tribes known as Chichemec – which implies ‘barbarian’ – arrived in the Valley of Mexico from about 900 AD and began to construct cultures based on what remained of their predecessors’. The Toltecs were followed by the Aztecs, who arrived at the end of the twelfth century but did not begin to construct the great city of Tenochtitlan until 1345. Shifting alliances and constant warfare eventually gave the Aztecs control over much of central Mexico, although the Mixtecs in Oaxaca were not subjected until just before the arrival of the Spanish. The Maya were never conquered.

|

4

|

FALL |

A Spanish expedition led by Hernan Cortés landed on the Gulf coast near Veracruz on 21 April 1519 with just 500 men, fighting dogs and horses. Cortés promptly burned the boats that had carried them from Spain to prevent his men from returning. In less than three years they were to establish control over most of Mexico. Their biggest asset was their ability to forge alliances with warring factions within the Aztec empire. They used gunpowder for surprise effect. The single-mindedness of their purpose (to enrich themselves with gold) and novelties such as the gunpowder helped to intimidate their opponents. Moctezuma was killed, probably by his own people, but fierce resistance continued under his successor Cuauhtémoc until Tenochtitlan finally fell to Spanish control on 13 August 1521.

|

5

|

COLONY |

Quickly the Spanish monarchy established control over what it called Nueva España (New Spain) and ruled for 300 years through a series of viceroys. The total population of Mexico fell from an estimated 25 million at the time of the Conquest to just six million at the start of the nineteenth century, of which no more than half were indigenous peoples. Many thousands were massacred by the Spanish, but most fell victim to European diseases against which they had no immunity. The Catholic Church enforced mass conversions and became the most powerful and wealthy institution in the colony. Annual convoys of galleons carried silver and gold as tribute to the Spanish crown. Only gachupines, Spaniards from Spain, could hold high office: criollos (Creoles, born in Mexico of Spanish blood) and mestizos (of mixed race) were relegated to positions of inferior status while the indigenous peoples were treated as slaves.

|

6

|

INDEPENDENCE |

The French Revolution and the American Wars of Independence coincided with a decline of Spanish power. A Creole priest, Miguel Hidalgo, raised the cry ‘Mexicanos, Viva Mexico!‘ on the steps of his parish church in Dolores on 16 September 1810, the date recognized today as marking Mexican independence. But throughout the nineteenth century no lasting settlement between competing factions and ideas was ever reached. General Santa Ana became president or dictator on no less than 11 separate occasions. Mexico was prey to foreign powers. In 1845 the US annexed Texas and in 1848 invaded Mexico City; it paid $15 million for most of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California. France temporarily invaded Veracruz in 1838 and in 1861 Napoleon III took Mexico City where he installed a Hapsburg archduke, Maximilian, as ’emperor’ for a brief period. Benito Juárez, a Zapotec Indian and the only indigenous person ever to be president of Mexico, enacted reforms in 1867 aimed at reducing the power and wealth of the Catholic Church: church property was confiscated, marriages and burials became secular ceremonies and priests were forbidden to wear their robes in public.

|

7

|

REVOLUTION |

Porfirio Díaz, a general, took power in 1876 and retained it as a virtual dictator until 1911. He enforced a policy of ruthless industrial ‘modernization’. Almost all of it was, however, controlled by foreign investors. In the countryside the power of large landowners was vastly enhanced. In 1910 Francisco Madero stood against Díaz in the presidential election and was imprisoned, but he escaped to Texas where he called for Mexicans to rise up against Díaz. Armed revolutionary groups emerged, led by Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco in the north and Emiliano Zapata in the south. Land for the peasantry, and the slogan Tierra y Libertad (‘Land and Liberty’), were at the centre of revolutionary demands. In 1917 a congress established a new constitution containing most of the revolutionary agenda (a mandatory eight-hour day, national ownership of mineral rights, the distribution of land to the peasantry) which remains the basis of the Mexican Constitution today.

|

8

|

INSTITUTION |

Relatively minor disturbances continued throughout much of the 1920s; halting progress was made on the revolutionary agenda, and when President Obregon was forced to stand down for breaching the ‘no re-election’ clause of the constitution in 1928 the long rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) effectively began. Lázaro Cárdenas was elected president in 1934 and he gave new pace to the distribution of land and nationalized the Mexican oil industry. Four decades of astonishing industrial growth followed a model of ‘corporatist’ intervention at every level of Mexican society. Despite Mexico’s oil wealth, this model collapsed under a mountain of debt in 1982.