Scientists Put a Face on an Ancient Human Ancestor

A cranium 3.8 million years old helps fill out the picture of the earliest human skull from an era with a nearly-vacant fossil record

Scientists on Wednesday announced their discovery of a face from the earliest moments of human evolution: a cranium 3.8 million years old belonging to a creature that stood on the cusp of apes and humans.

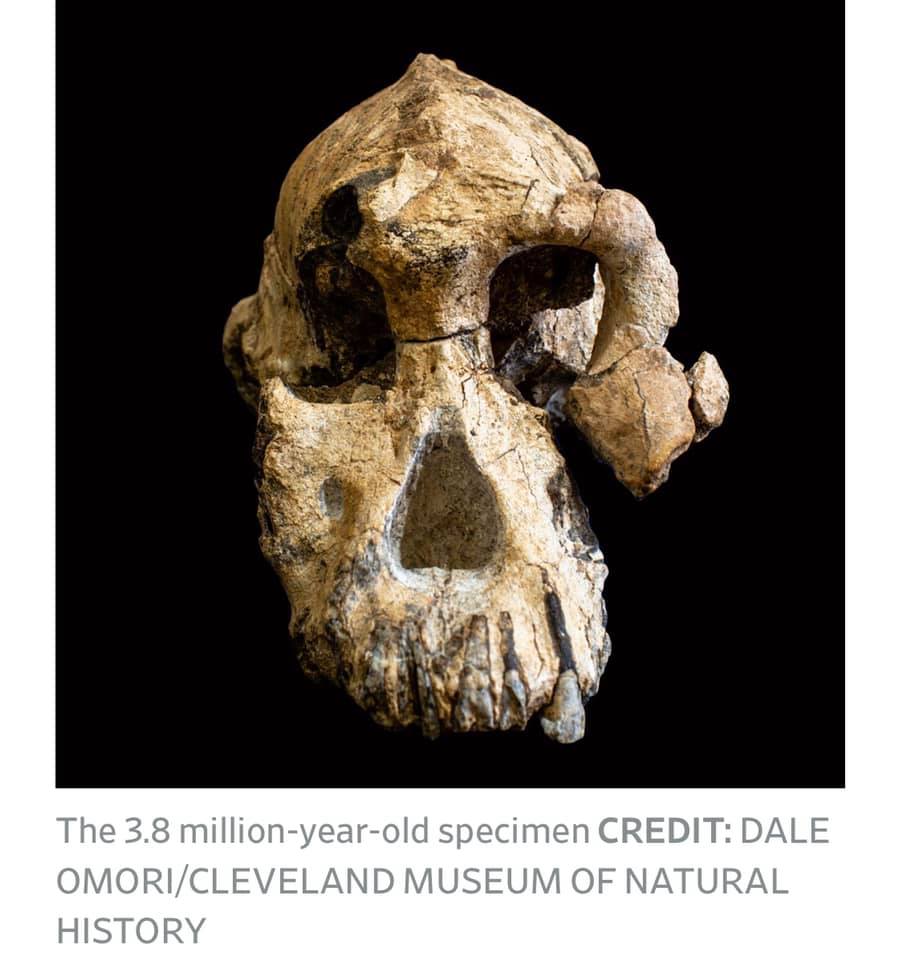

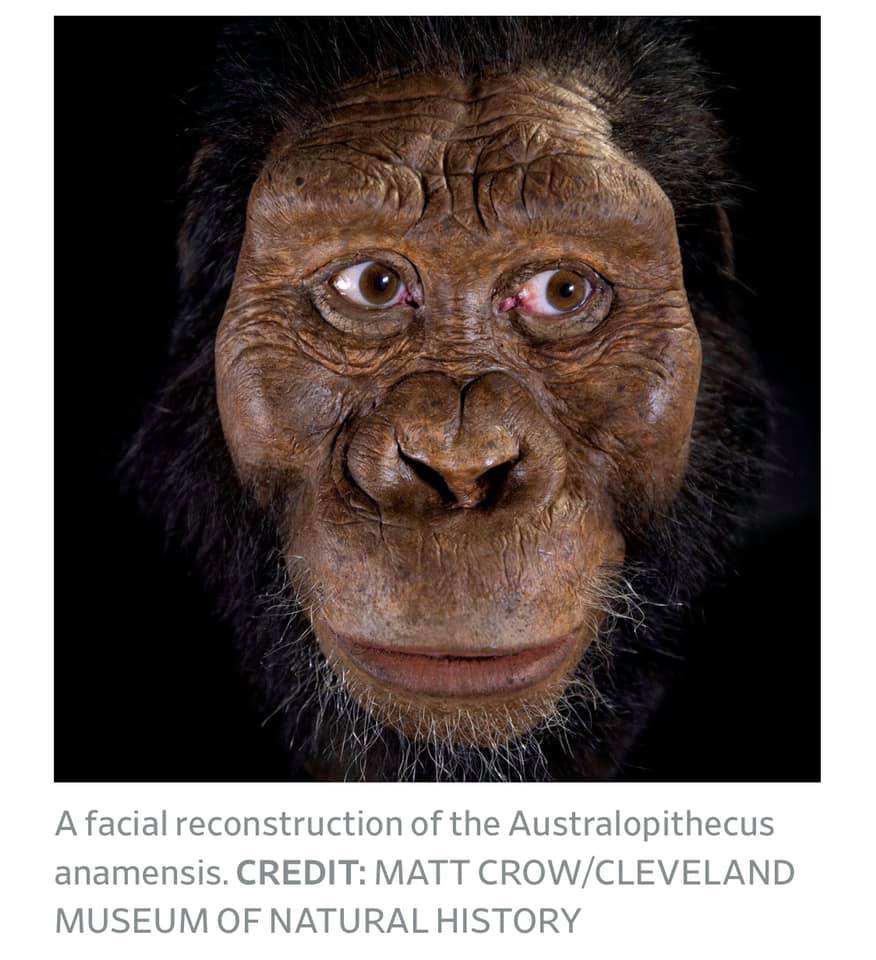

The fossilized head bones reveal for the first time the blunt snout, broad cheeks and narrow forehead of a distant human relation called Australopithecus anamensis, who may have vied for survival in the primeval scrub of East Africa at the same time as the iconic human ancestor “Lucy” and her kin, the scientists said. The researchers published details of their find in the journal Nature.

“What we see is a very primitive face,” said paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, who led the international research team that discovered the nearly complete cranium in Ethiopia. Until now, the anamensis species, among the oldest in the human family tree, had been known only from teeth, a few broken jaw bones, part of an elbow and a shin.

“It helps fill out a picture of the earliest human skull in a period that until now has been almost vacant in the fossil record,” said paleoanthropologist William Kimbel, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, who recently examined the fossil. He wasn’t part of the discovery team. “It provides a baseline from which we can eventually see the emergence of the human face.”

Fred Spoor, an expert in fossil human skulls at the Natural History Museum in London, who wasn’t involved in the discovery, said, “This cranium looks to become another celebrated icon of human evolution.”

Even so, it isn’t so easy to discern something recognizably human in a cranium that once held a brain about the size of a chimpanzee’s, several scientists said. It has relatively modern cheeks but unusually large canine teeth and a prominent crest of bone running along its forehead to anchor chewing muscles that were more powerful than those of a modern ape.

“It is surprisingly primitive,” said paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood at George Washington University, who wasn’t involved in the research. ”If you looked at it on a dark night with a bit of mist in the air, you’d have difficulty telling it from a chimp.”

In fact, it would require millions of years of adaptation to new foods, changing climates and the growing advantage of expressive features for communicating needs, to sculpt its facial structure into the sharp-chin, aquiline nose, flat cheeks and smooth forehead of contemporary humankind, several experts on human origins said.

“It is a big jump from the face of anamensis to you and me,” said Dr. Kimbel.

The researchers discovered the cranium in 2016 at a place called Woranso-Mille in Ethiopia’s Afar region, about 340 miles from the capital, Addis Ababa. The site is just over 30 miles from the Hadar, where in 1974 scientists discovered the world-famous skeleton of Lucy, a 3.2 million-year-old specimen of a closely related species called Australopithecus afarensis.

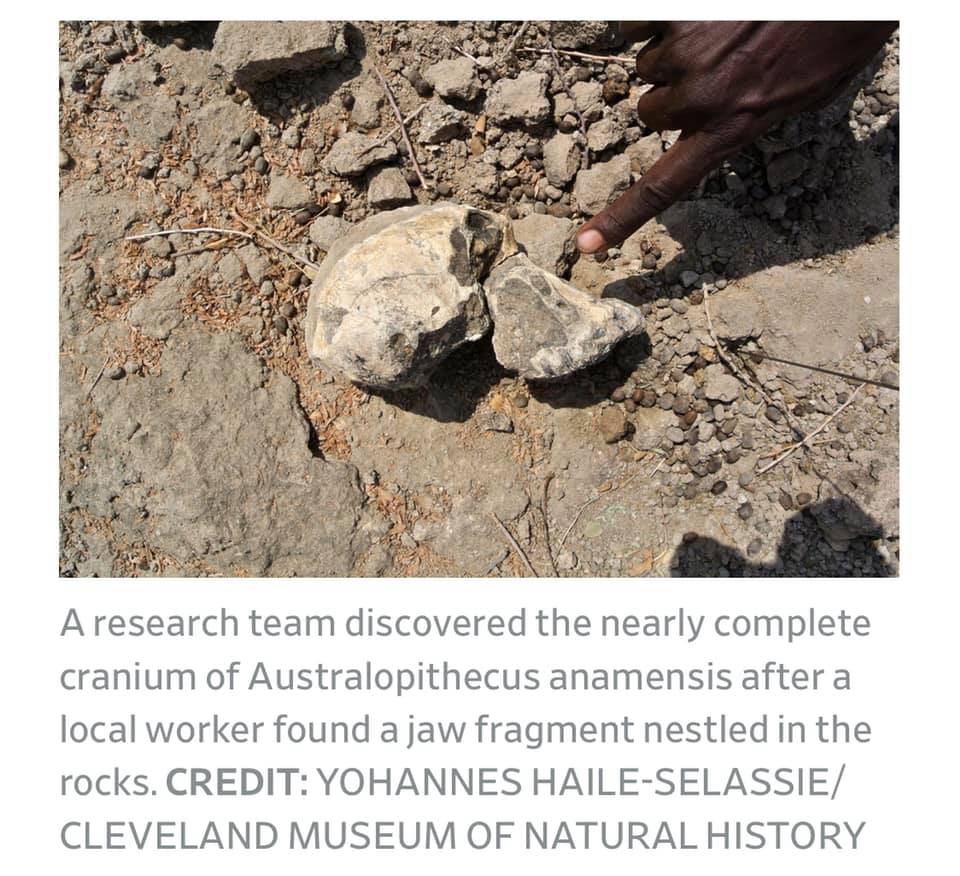

A local Afar worker named Ali Bereino found the first fragment, part of the upper jaw, nestled among the rocks. The researchers soon uncovered the rest of the cranium. They concluded that it belonged to a small adult male who likely lived and died along an ancient lake shore there, and had been washed into the sandy shallows where it was preserved.

Geologist Beverly Saylor of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and her colleagues determined the age of the fossil as 3.8 million years by dating minerals in nearby layers of volcanic rocks.

Already, the discovery is renewing a debate over the earliest humankind. In recent years, many researchers believed that the anamensis species vanished when slightly more advanced descendants like Lucy emerged.

Dr. Haile-Selassie and his colleagues suggested instead that the two species might have coexisted for up to 100,000 years or so, along with as many as three other small-brained prehuman species.

“I am far from persuaded,” said paleoanthropologist Tim D. White at the University of California Berkeley. He believes it more likely that these creatures are all variations of the same species. “This discovery is a great example of a very important fossil that does not require a redraw of our family tree.”

• Fossil Points to a Vanished Human Species in Himalayas (May 1)

• Fossil Evidence of New Human Species Found in Philippines (April 10)

• Researchers Say They Found the Oldest Known Line Drawing in a Cave in South Africa (Sept. 12, 2018)

• Scientists Find Oldest Known Specimens of the Human Species (June 7, 2017)

Other researchers found the distinctions plausible. “Just because one species gave rise to another, the source species doesn’t just disappear,” said Richard Potts, head of the human origins program at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “We’ve known for decades that the human family tree is branching and diverse.”

Only more fossil discoveries can settle the debate, the scientists said.

In the interim, the protruding features of the anamensis face make these distant human relatives more memorable. “It is good to finally be able to put a face on the name,” said expedition member Stephanie Melillo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who helped identify the cranium.

Write to Robert Lee Hotz at sciencejournal@wsj.com

Full access to the trusted insights you need

DOWNLOAD THE WSJ APP