Saponi Indians

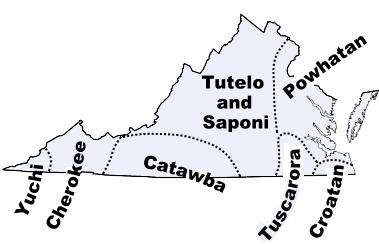

The Saponi Indians were a Siouan-speaking people who lived in the Virginia Piedmont near present-day Charlottesville. John Smith found them there, in a region he broadly labeled Monacan, in 1607. Sometime during the next several decades they moved south, seldom remaining stationary until the mid-eighteenth century. A small group of corn farmers and hunters, the Saponi moved to find protection from more powerful enemies.

In 1670 German explorer John Lederer found the Saponi among the Nahyssan on the Staunton River in Virginia. In the 1680s, they were on the upper Roanoke River, living adjacent to the Occaneechi. When John Lawson visited them in 1701, the Saponi were on the Yadkin River near present-day Salisbury, along with the Tutelo and Keyauwee. The Saponi chief told Lawson that the three tribes were planning to join and move again. In 1714 the Saponi, Occaneechi, Tutelo, and other small tribes concluded a treaty with Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood to return to that colony and settle on a six-mile-square reservation laid out on the Meherrin River. Named Fort Christanna, the reservation was to be a refuge for Piedmont Indians willing to serve the Virginia settlements as frontier scouts. In 1729 the Saponi and their friends abandoned the fort and headed for the Catawba River, where the Catawba Nation offered sanctuary.

Staunton River in Virginia. In the 1680s, they were on the upper Roanoke River, living adjacent to the Occaneechi. When John Lawson visited them in 1701, the Saponi were on the Yadkin River near present-day Salisbury, along with the Tutelo and Keyauwee. The Saponi chief told Lawson that the three tribes were planning to join and move again. In 1714 the Saponi, Occaneechi, Tutelo, and other small tribes concluded a treaty with Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood to return to that colony and settle on a six-mile-square reservation laid out on the Meherrin River. Named Fort Christanna, the reservation was to be a refuge for Piedmont Indians willing to serve the Virginia settlements as frontier scouts. In 1729 the Saponi and their friends abandoned the fort and headed for the Catawba River, where the Catawba Nation offered sanctuary.

In 1731 growing dissatisfaction with their situation caused the Saponi to fragment. A few remained with the Catawba, but most left. Some moved north to join those Tuscaroras who remained in North Carolina after the Tuscarora War (1711-13); others migrated to New York, where the Cayuga, one of the Six Nations of Iroquois, adopted them. Still others drifted toward the English settlements, where they were ultimately absorbed into the general population. By the early 2000s the Haliwa-Saponi tribe was a small, state-recognized tribe with headquarters in the town of Hollister in Halifax County.In 1670 German explorer John Lederer found the Saponi among the Nahyssan on the Staunton River in Virginia. In the 1680s, they were on the upper Roanoke River, living adjacent to the Occaneechi. When John Lawson visited them in 1701, the Saponi were on the Yadkin River near present-day Salisbury, along with the Tutelo and Keyauwee. The Saponi chief told Lawson that the three tribes were planning to join and move again. In 1714 the Saponi, Occaneechi, Tutelo, and other small tribes concluded a treaty with Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood to return to that colony and settle on a six-mile-square reservation laid out on the Meherrin River. Named Fort Christanna, the reservation was to be a refuge for Piedmont Indians willing to serve the Virginia settlements as frontier scouts. In 1729 the Saponi and their friends abandoned the fort and headed for the Catawba River, where the Catawba Nation offered sanctuary.

In 1731 growing dissatisfaction with their situation caused the Saponi to fragment. A few remained with the Catawba, but most left. Some moved north to join those Tuscaroras who remained in North Carolina after the Tuscarora War (1711-13); others migrated to New York, where the Cayuga, one of the Six Nations of Iroquois, adopted them. Still others drifted toward the English settlements, where they were ultimately absorbed into the general population. By the early 2000s the Haliwa-Saponi tribe was a small, state-recognized tribe with headquarters in the town of Hollister in Halifax County.In 1670 German explorer John Lederer found the Saponi among the Nahyssan on the Staunton River in Virginia. In the 1680s, they were on the upper Roanoke River, living adjacent to the Occaneechi. When John Lawson visited them in 1701, the Saponi were on the Yadkin River near present-day Salisbury, along with the Tutelo and Keyauwee. The Saponi chief told Lawson that the three tribes were planning to join and move again. In 1714 the Saponi, Occaneechi, Tutelo, and other small tribes concluded a treaty with Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood to return to that colony and settle on a six-mile-square reservation laid out on the Meherrin River. Named Fort Christanna, the reservation was to be a refuge for Piedmont Indians willing to serve the Virginia settlements as frontier scouts. In 1729 the Saponi and their friends abandoned the fort and headed for the Catawba River, where the Catawba Nation offered sanctuary.

References:

James H. Merrell, The Indians’ New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal (1989).

Douglas L. Rights, The American Indian in North Carolina (2nd ed., 1957).

SAPONI HISTORY by Scott Preston Collins

|

|

||

| This tribe lived on Yadkin River and in other parts of the state of North Carolina for a certain period.

The name Saponi is evidently a corruption of Monasiccapano or Monasukapanough, which, as shown by Bushnell, is probably derived in part from a native term “moni seep,” signifying “shallow water.” Paanese is a corruption and in no way connected with the word “Pawnee.” The Saponi belonged to the Siouan linguistic family, their nearest relations being the Tutelo. The earliest known location of the Saponi has been identified by Bushnell (1930) with high probability with “an extensive village site on the banks of the Rivanna, in Albemarle County, Virginia, directly north of the University of Virginia and about one-half mile up the river from the bridge of the Southern Railway.” This was their location when, if ever, they formed a part of the Monacan Confederacy. This tribe lived on the Yadkin River and in other parts of North Carolina for a certain period. The principal Saponi settlement usually bore the same name as the tribe or, at least, it has survived to us under that name. In 1670, Lederer reports another which he visited called Pintahae, situated not far from the main Saponi town after it had been removed to Otter Creek, southwest of present-day Lynchburg, Virginia (Lederer, 1912), but this was probably the Nahyssan town. As first pointed out by Mooney (1895), the Saponi tribe is identical with the Monasukapanough which appears on Smith’s map as though it were a town of the Monacan and may in fact have been such. Before 1670, and probably between 1650 and 1660, they moved to the southwest and probably settled on Otter Creek, as above indicated. In 1670 they were visited by Lederer in their new home and by Thomas Batts a year later. Not long afterward they and the Tutelo moved to the junction of the Staunton and Dan Rivers, where each occupied an island in Roanoke River in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. This movement was to enable them to escape the attacks of the Iroquois, and for the same reason they again moved south before 1701, when Lawson found them on Yadkin River near the present site of Salisbury, NC. Soon afterward, they left this place and gravitated toward the white settlements in Virginia. They evidently crossed the Roanoke River before the Tuscarora War of 1711, establishing themselves a short distance east of it and fifteen miles west of the present Windsor, Bertie County, NC. A little later they, along with the Tutelo and some other tribes, were placed by Governor Spotswood near Fort Christanna, ten miles north of Roanoke River about the present Gholsonville, Brunswick County, Virginia. The name of Sappony Creek in Dinwiddie County, dating back to 1733 at least, indicates that they sometimes extended their excursions north of Nottoway River. By the treaty of Albany (1722) the Iroquois agreed to stop incursions on the Virginia Indians and, probably about 1740, the greater part of the Saponi and the Tutelo moved north stopping for a time at Shamokin, PA, about the site of Sunbury. One band, however, remained in the south, in Granville County, NC, until at least 1755, when they comprised fourteen men and fourteen women. In 1753, the Cayuga Iroquois formally adopted this tribe and the Tutelo. Some of them remained on the upper waters of the Susquehanna in Pennsylvania until 1778, but in 1771 the principal section had their village in the territory of the Cayuga, about two miles south of Ithaca, NY. They are said to have separated from the Tutelo in 1779 at Niagara, when the latter fled to Canada, and to have become lost, but a portion, at least, were living with the Cayuga on Seneca River in Seneca County, NY, in 1780. Besides the Person County Indians, a band of Saponi Indians remained behind in North Carolina which seems to have fused with the Tuscarora, Meherrin, and Machapunga and gone north with them in 1802. The Saponi and the Tutelo are identified by Mooney (1928) as remnants of the Manahoac and Monacan with an estimated population of 2,700 in 1600. In 1716, the Huguenot Fontaine found 200 Saponi, Manahoac, and Tutelo at Fort Christanna. In 1765, when they were living on the upper Susquehanna, the Saponi are said to have had 30 warriors. The main North Carolina band counted 20 warriors in 1761, and those in Person County, fourteen men and fourteen women in 1755. A small place called Sapona, in Davidson County, NC, east of the Yadkin River, preserves the name of the Saponi |