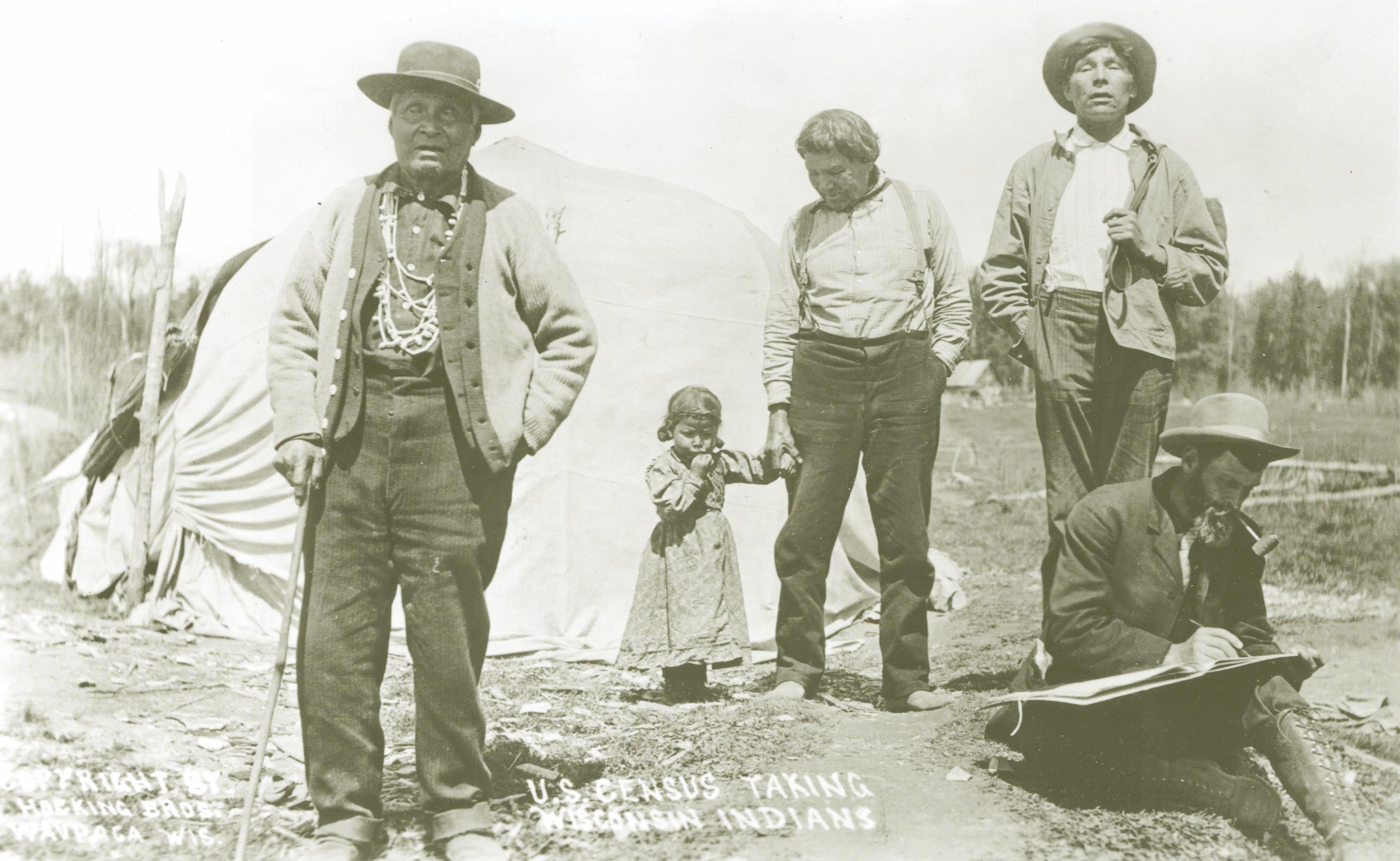

But this raises the question of whose idea of race was recorded. The answer is, that of the census taker. The census takers were provided instructions and they recorded the ethnic category of various family members based on their perception of the family when they visited. In most cases, this wasn’t a problem. But if you are racially mixed and trying to find and interpret data about your family, these results can be confusing, especially if in one census they are white, in another mulatto and maybe in another black. In some census years, there was no category at all for Indian. In others, all free people of color were recorded in one group. Where your family fell was up to the census taker, not your family members.

Let’s take a look at what the various census instructions to enumerators and census forms said about Indians.

1790 – “Omitting Indians not taxed, distinguishing free persons, including those bound to service, from all others.” Indians living “wild,” generally meaning plains Indians in the west, or on reservations were not taxed, but those who were enumerated were recorded in the “all other free” column on the census form.

1800 – Indians living off of reservations and not “wild” would have been recorded in the “all other free persons” column on the census form. Options were free white, slave and “all other free persons.”

1810 – Indians living off of reservations would have been recorded in the “all others” column on the census form. Options were free white, slave and “all other.”

1820 – Indians living off of reservations would have been recorded in the “free colored persons” categories. Other options were free whites, slaves and “all others except Indians not taxed.”

1830 – Indians living off of reservations and not “wild” would have been recorded in the “free colored persons” category. Other options were free whites and slaves.

1840 – Essentially the same as 1830 with the exception that an additional column labeled “pensioners for revolutionary or military services” with a blank for the pensioner’s name to be included and applies to all individuals.

1850 – 1850 is the first census in which every individual in the household was enumerated. In prior years, only the name of the head of household was recorded and other household members were recorded by age grouping by category. In 1850, the instructions say that Indians not taxed (meaning on reservations) were not to be enumerated and the categories for race were white, black, mulatto. So if your ancestor looked “dark” and was an Indian, chances are they were recorded as M for mulatto. There was no “Indian” category until 1860.

1860 – Indians not taxed were not enumerated. However, the categories differed a bit this year. “The families of Indians who have renounced tribal rule, and who under State or Territorial laws exercise the rights of citizens, are to be enumerated. In all such cases write “Ind.” opposite their names, in column 6, under heading ‘Color.’”

There is a census in Indian Territory, but Indians are not included.

1870 – Instructions said, “”Indians not taxed’ are not to be enumerated on schedule 1. Indians out of their tribal relations, and exercising the rights of citizens under State or Territorial laws, will be included. In all cases write “Ind.” in the column for “Color.” Although no provision is made for the enumeration of “Indians not taxed,” it is highly desirable, for statistical purposes, that the number of such persons not living upon reservations should be known. Assistant marshals are therefore requested, where such persons are found within their subdivisions, to make a separate memorandum of names, with sex and age, and embody the same in a special report to the census office.”

The form gave these race options: Color – White (W), black (B), mulatto (M), Chinese (C), Indian (I).

There was no census of Indian people in Indian Territory. However, this National Archives article discusses Indians in the census between 1860 and 1880 and states that in 1870 half-breed people who had assimilated and adopted white ways were to be recorded as white.

1880 – Instructions said, “It is the prime object of the enumeration to obtain the name, and the requisite particulars as to personal description, of every person in the United States, of whatever age, sex, color, race, or condition, with this single exception, viz.: that “Indians not taxed” shall be omitted from the enumeration.

By the phrase “Indians not taxed” is meant Indians living on reservations under the care of Government agents, or roaming individually, or in bands, over settled tracts of country.

Indians, not in tribal relations, whether full-bloods or half-breeds, who are found mingled with the white population, residing in white families, engaged as servants or laborers, or living in huts or wigwams on the outskirts of towns or settlements are to be regarded as a part of the ordinary population of the country for the constitutional purpose of the apportionment of Representatives among the States, and are to be embraced in the enumeration.”

However, the 1880 instructions for “color” are not specific as to how to record Indians or those of mixed heritage. “Color.-It must not be assumed that, where nothing is written in this column, “white” is to be understood. The column is always to be filled. Be particularly careful in reporting the class mulatto. The word is here generic, and includes quadroons, octoroons, and all persons having any perceptible trace of African blood. Important scientific results depend upon the correct determination of this class in schedules 1 and 5.”

The form gave these options: Color – White, W; black, B; Mulatto, Mu; Chinese, C; Indian, I.

Beginning in 1885, special Indian Census were taken on reservations. This continued until 1940.

1890 – The 1890 census was destroyed, but here are the instructions: “Whether white, black, mulatto. quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian.-Write white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian, according to the color or race of the person enumerated. Be particularly careful to distinguish between blacks, mulattos, quadroons, and octoroons. The word “black” should be used to describe those persons who have three-fourths or more black blood; “mulatto,” those persons who have from three-eighths to five-eighths black blood; “quadroon,” those persons who have one-fourth black blood; and “octoroon,” those persons who have one-eighth or any trace of black blood.”

1900 – In 1900, the instructions become less specific: Although they don’t say so here, we know that Indians on reservations are still not consistently enumerated.

“Column 5. Color or race.-Write “W” for white; “B” for black (negro or of negro descent); “Ch” for Chinese; “JP” for Japanese, and “In” for Indian, as the case may be.”

The census bureau says that beginning in 1900, Indians on reservations were also enumerated in the general census, but I have not found this to always be the case. I do find them consistently by 1930.

A special Indian census form with separate instructions was included, although these are often only recorded at the end of the county census roll and sometimes not indexed when indexing occurred. These were supposed to be for people both on reservations and off who considered themselves to be Indian. These are particularly valuable records.

1910 instructions: “Color or race.-Write “W” for white; “B” for black; “Mu” for mulatto; “Ch” for Chinese; “Jp” for Japanese; “In” for Indian. For all persons not falling within one of these classes, write “Ot” (for other), and write on the left-hand margin of the schedule the race of the person so indicated.”

Again a special Indian census form and instructions were included.

1920 instructions: “Color or race.-Write “W” for white, “B” for black; “Mu” for mulatto; “In” for Indian; “Ch” for Chinese; “Jp” for Japanese; “Fil” for Filipino; “Hin” for Hindu; “Kor” for Korean. for all persons not falling within one of these classes, write “Ot” (for other), and write on the left-hand margin of the schedule the race of the person so indicated.”

Things changed dramatically between 1920 and 1930 for Indians. In 1924, Indians were made American citizens. Before 1924, Indians who lived on reservations were considered to be citizens of their tribe and not American citizens. This harkens back to the 1830s lawsuits about sovereign tribal rights.

Before the 1930 census, Indians living on reservations were not always enumerated on the general census. There were special Indian census schedules taken, but not on the decade marks like the regular census, and not as detailed, generally lists of families with ages. But in 1930, all Indians were included in the census, and the instructions became much more robust as well. Some Indians were included in the 1900-1920 census schedules, but not all, although according to the instructions, they were all supposed to be included. Mixed race people and Indians living off of the reservation were included. Indians living on reservations are the people missing from the census prior to 1930. Fortunately for genealogists, if your ancestor was living on a reservation in the 1900s, you likely know about it.

1930 instructions:

“150. Column 12. Color or race.-Write “W” for white, “B” for black; “Mus” for mulatto; “In” for Indian; “Ch” for Chinese; “Jp” for Japanese; “Fil” for Filipino; “Hin” for Hindu; “Kor” for Korean. For a person of any other race, write the race in full.

“151. Negroes.-A person of mixed white and Negro blood should be returned as a Negro, no matter how small the percentage of Negro blood. Both black and mulatto persons are to be returned as Negroes, without distinction. A person of mixed Indian and Negro blood should be returned a Negro, unless the Indian blood predominates and the status as an Indian is generally accepted in the community.

152. Indians.-A person of mixed white and Indian blood should be returned as Indian, except where the percentage of Indian blood is very small, or where he is regarded as a white person by those in the community where he lives. (See par. 151 for mixed Indian and Negro.)

153. For a person reported as Indian in column 12, report is to be made in column 19 as to whether “full blood” or “mixed blood,” and in column 20 the name of the tribe is to be reported. For Indians, columns 19 and 20 are thus to be used to indicate the degree of Indian blood and the tribe, instead of the birthplace of father and mother.

154. Mexicans.-Practically all Mexican laborers are of a racial mixture difficult to classify, though usually well recognized in the localities where they are found. In order to obtain separate figures for this racial group, it has been decided that all person born in Mexico, or having parents born in Mexico, who are not definitely white, Negro, Indian, Chinese, or Japanese, should be returned as Mexican (“Mex”).

155. Other mixed races.-Any mixture of white and nonwhite should be reported according to the nonwhite parent. Mixtures of colored races should be reported according to the race of the father, except Negro-Indian (see par. 151).”

In the “place of birth” section, we find these instructions for Indians:

“174a. For the Indian population, which is practically all of native parentage, these columns are to be used for a different purpose. In column 19 is to be entered, in place of the country of birth of the father, the degree of Indian blood, as, “full blood” or “mixed blood.” In column 20 is to be entered, in place of the country of birth of the mother, the tribe to which the Indian belongs.’

1940 – The 1940 census is the last census that has been released, and the instructions that year were:

“453. Column 10. Color or Race.-Write “W” for white; “Neg” for Negro; “In” for Indian; “Chi” for Chinese; “Jp” for Japanese; “Fil” for Filipino; “Hi” for Hindu; and “Kor” for Korean. For a person of any other race, write the race in full.

454. Mexicans.-Mexicans are to be regarded as white unless definitely of Indian or other nonwhite race.

455. Negroes.-A person of mixed white and Negro blood should be returned as Negro, no matter how small a percentage of Negro blood. Both black and mulatto persons are to be returned as Negroes, without distinction. A person of mixed Indian and Negro blood should be returned as a Negro, unless the Indian blood very definitely predominates and he is universally accepted in the community as an Indian.

456. Indians.-A person of mixed white and Indian blood should be returned as an Indian, if enrolled on an Indian agency or reservation roll, or if not so enrolled, if the proportion of Indian blood is one-fourth or more, or if the person is regarded as an Indian in the community where he lives.

457. Mixed Races.-Any mixture of white and nonwhite should be reported according to the nonwhite parent. Mixtures of nonwhite races should be reported according to the race of the father, except that Negro-Indian should be reported as Negro.”

In addition, the “mother tongue” recorded was to be the tribal language.

1950 – Although the 1950 census has not been released, the categories are quite interesting and the 1950 census should help genealogists who are attempting to sort through their family history. This census took into consideration special mixed communities. The instructions for “Race” are as follows.

“114. Item 9. Determining and entering race.-Write “W” for white; “Neg” for Negro; “Ind” for American Indian; “Chi” for Chinese; “Jap” for Japanese; “Fil” for Filipino. For a person of any other race, write the race in full. Assume that the race of related persons living in the household is the same as the race of your respondent, unless you learn otherwise. For unrelated persons (employees, hired hands, lodgers, etc.) you must ask the race, because knowledge of the housewife’s race (for example) tells nothing f the maid’s race.

115. Mexicans.-Report “white” for Mexicans unless they are definitely of Indian or other nonwhite race.

116. Negroes.-Report “Negro” (Neg) for Negroes and for persons of mixed white and Negro parentage. A person of mixed Indian and Negro blood should be returned as a Negro, unless the Indian blood very definitely predominates and he is accepted in the community as an Indian. (Note, however, the exceptions described in par. l18 below.)

117. American Indians.-Report “American Indian” (Ind) for persons of mixed white and Indian blood if enrolled on an Indian Agency or Reservation roll; if not so enrolled, they should still be reported as Indian if the proportion of Indian blood is one-fourth or more, or if they are regarded as Indians in the community where they live. (See par. 116 for persons of mixed Indian and Negro blood and also exceptions noted in par. 118.) In those counties where there are many Indians living outside of reservations, special care should be taken to obtain accurate answers to item 9.

118. Special communities.-Report persons of mixed white, Negro, and Indian ancestry living in certain communities in the Eastern United States in terms of the name by which they are locally known.

The communities in question are of long standing and are locally recognized by special names, such as ‘”Croatian,” “Jackson White,” “We-sort,” etc. Persons of mixed Indian and Negro ancestry and mulattoes not living in such communities should be returned as “Negro” (see par. 116). When in doubt, describe the situation in a footnote.

119. Mixed parentage.-Report race of nonwhite parent for persons of mixed white and nonwhite races. Mixtures of nonwhite races should be reported according to the race of the father. (Note, however, exceptions detailed in pars. 116 and 118 above.)

120. India.-Persons originating in India should be reported as ‘Asiatic Indians.’”

The 1960 census is unremarkable and includes Indian as a category with no specific instructions.

Then came 1970 and the census changed dramatically. People were asked about their race and race was no longer recorded based on the interpretation of the census taker. For Indian, there was a blank beside the category with the word “tribe” that was to be filled in. As of the 2010 census, this tribal question remains on the forms.

Between 1980 and 2000, the Native American population inthe US increased 110%. Now clearly, this was not a matter of actual population growth, but the difference between what the previous census takers saw and the self-identification of individuals. There seems to be quite a chasm between perception and identity.

How to identify an Indian or an Indian mixed race person, especially one not living on a reservation, seems to have been a problem that has plagued census takers and therefore the government, and now genealogists, since the beginning of the census records more than 200 years ago.

You can read more about how the statistics about and individual perception of race in American has changed due to census changes here.