HOW THE LENAPES CELEBRATED

By Leo H. Carney

Published: November 22, 1981

EVERY fall beginning hundreds of years ago, the Lenape Indians would hold a long harvest festival to say wanishi -thank you – to their Creator and lesser gods.

EVERY fall beginning hundreds of years ago, the Lenape Indians would hold a long harvest festival to say wanishi -thank you – to their Creator and lesser gods.

It was a time when Meesinghawleekum, the spirit who kept watch over all animals of the forest, visited Lenape campsites to herald the arrival of the hunting season.

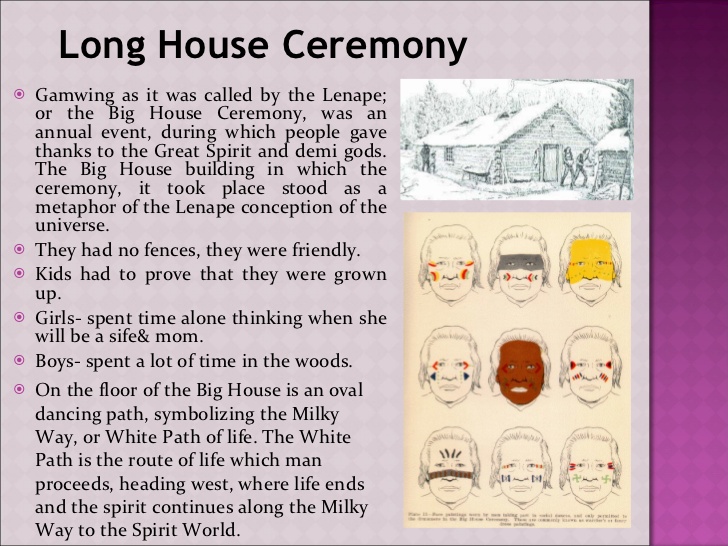

According to historical references and recent interviews, the Lenape of what is now New Jersey observed a ”thanksgiving” that lasted about 10 or 12 days. However, their ceremony, which was known as gamwing, was a far cry from the holiday that is customarily associated with the Mayflower, turkey and cranberry sauce.

James Revey (Lone Bear), who heads the New Jersey Indian Office, an association of legitimately descended Lenapes – or Delaware Indians, as they also are called – explained the ceremony.

”It was a time when our ancestors sang about their visions and danced happy dances,” he said. ”It was in reference to, and in thanks for, all that the Creator had given them and a feast in which all shared many types of food.

”There were turkeys then, of course, but deer was the main dish. A deer was hunted and brought in as part of the ceremony. ”Gamwing was a happy time because people lived so far away from each other and were glad to see one another.” Mr. Revey and others said the focal point of the gamwing was the ”big house,” a high-ceilinged structure measuring about 60 by 40 feet. It was there that the sachem, or chief, lived with his family.

However, half of the house was devoted to ceremonial functions, and that is where the Lenape told of their dreams and nightmares, danced long into the night and exchanged gifts, including wampum. In those days, wampum was the polished shells of the hard clam, a species still found in New Jersey waters.

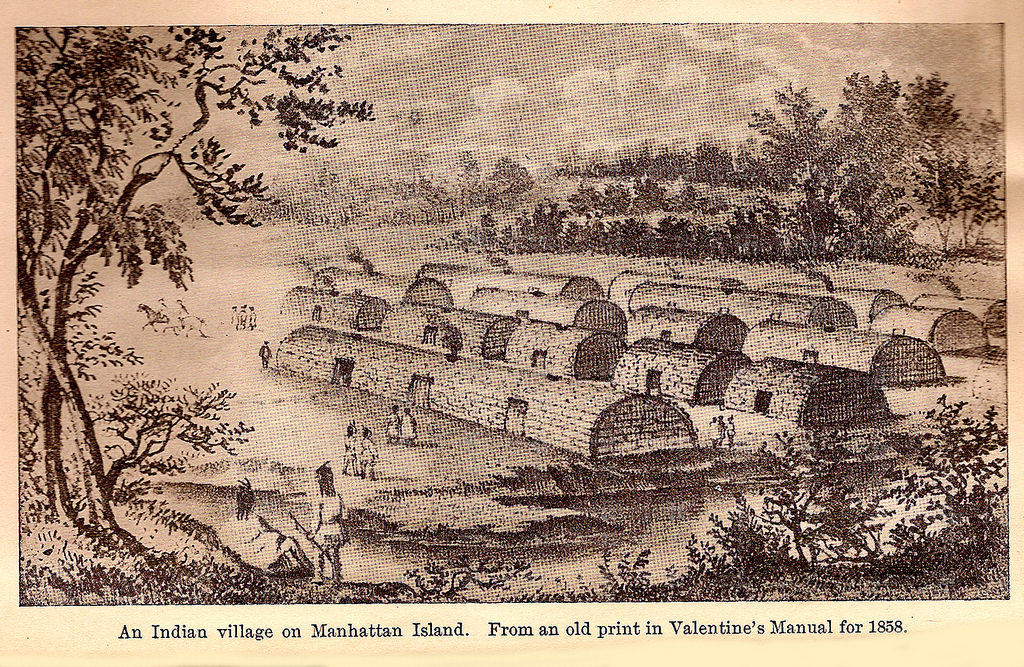

Dr. Frank Esposito, acting dean of education at Kean College in Union and a long-time student of the Lenape, said in an interview that members of the tribe inhabited the Delaware Valley, particularly just south of Trenton, as well as areas along the Arthur Kill and the Raritan, South, Navesink, Passaic, Toms and Metedeconk Rivers and near what are now Manahawkin and Tuckerton. (The Arthur Kill separates New Jersey from Staten Island.)

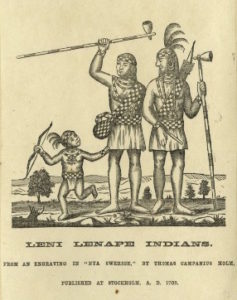

According to most estimates, 10,000 to 12,000 Lenape lived in New Jersey, northern Delaware, eastern Pennsylvania and southern New York around the time of contact with European settlers in the first half of the 17th century.

The Lenape were ”scattered throughout the state,” Dr. Esposito said. As he explained it, they originally occupied unfortified hamlets, generally made up of extended family units of about 100 people. ”It was not our idea of an Indian village in the West or anything like that,” Dr. Esposito said. The menu of the big feast consisted of deer, turkey and squirrel, and what Mr. Revey referred to as ”the three sisters” – squash, beans and corn. Corn was a staple of the Lenape diet and was prepared and eaten in several ways, including mush and muffins flavored with maple or birch syrup.

Other Lenape dishes included smoked oysters, clams, dried and smoked fish, walnuts and artichokes. Historians relate that prayer offered to the Creator and lesser deities was an intregal part of Lenape culture. They believed that every animal had a spirit, that they and everything in their world were interrelated and that the land was their ”Mother Earth,” a cornucopia that could never be owned and should never be abused.

Other Lenape dishes included smoked oysters, clams, dried and smoked fish, walnuts and artichokes. Historians relate that prayer offered to the Creator and lesser deities was an intregal part of Lenape culture. They believed that every animal had a spirit, that they and everything in their world were interrelated and that the land was their ”Mother Earth,” a cornucopia that could never be owned and should never be abused.

The Lenape also may have been among New Jersey’s original conservationists in yet another sense. Accounts of their hunting, food preparation and tool-making show that every conceivable part of an animal was put to use. For example, certain bones of the deer were used for fish hooks, and other, larger, bones were used as spoons or spades. The skin was made into clothing and the blood was drained into a kettle in which the venison was cooked.

According to several historical references, Lenapes took from the land, forests and waters only what they needed to sustain them. Leo H. Carney