The Aztecs and Mexico City: 14th century

The Aztecs are a tribe, according to their own legends, from Aztlan somewhere in the north of modern Mexico. From this place, which they leave in about the 12th century AD, there derives the name Aztecs by which they are known to western historians. Their own name for themselves is the Mexica, which subsequently provides the European names for Mexico City and Mexico.

The Aztecs are a tribe, according to their own legends, from Aztlan somewhere in the north of modern Mexico. From this place, which they leave in about the 12th century AD, there derives the name Aztecs by which they are known to western historians. Their own name for themselves is the Mexica, which subsequently provides the European names for Mexico City and Mexico.

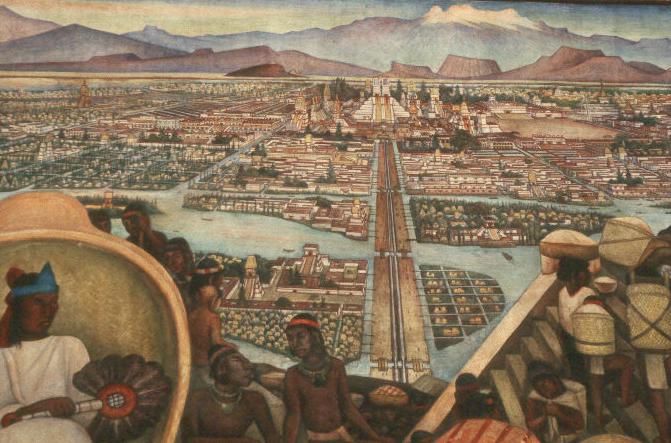

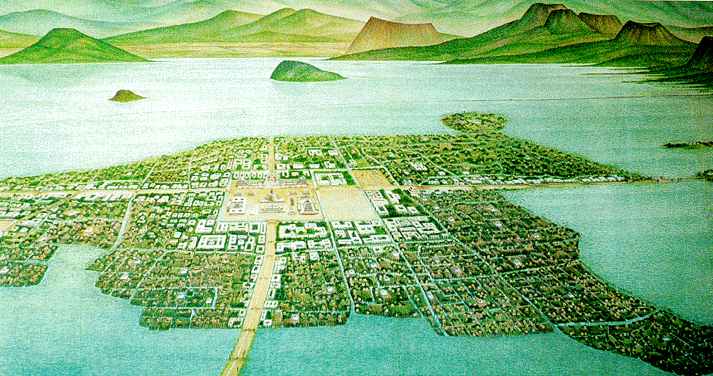

After two centuries of migration and warfare, the Aztecs finally settle within the area now covered by Mexico City. They choose an uninhabited island in Lake Tetzcoco. This is either in the year 1325 or, more probably, 1345. (The difference in date depends on how the Mesoamerican 52-year calendar cycle is integrated with the chronology of the Christian era). They call their settlement Tenochtitlan.

Their prospects in this place, where they are surrounded by enemy tribes, seem as unpromising as those of the Venetians on their bleak lagoon islands a few centuries earlier. Like Venice, against all the odds, Tenochtitlan becames the centre of a widespread empire and it does so much more rapidly, stretching across central America within a century. But unlike Venice, this is not an empire of trade. It is based on the Aztecs’ ferocious cult of war.

Aztec sun rituals: 15th – 16th century

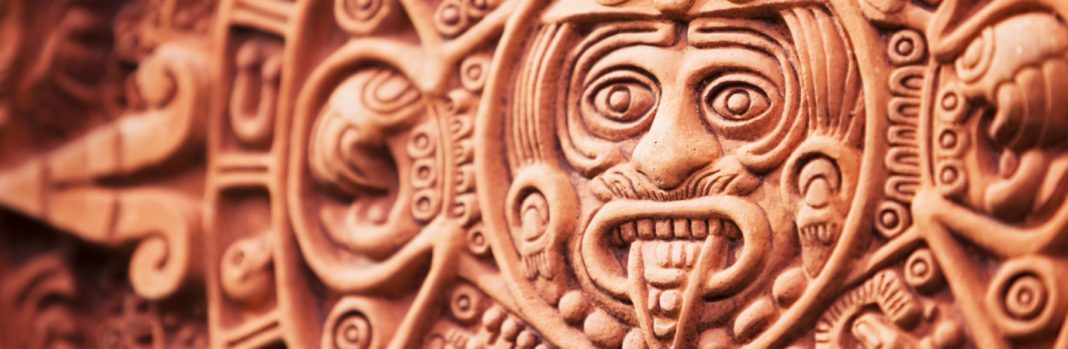

The patron deity of the Aztecs is Huitzilopochtli, god of war and symbol of the sun. This is a lethal combination. Every day the young warrior uses the weapon of sunlight to drive from the sky the creatures of darkness – the stars and the moon. Every evening he dies and they return. For the next day’s fight he needs strength. His diet is human blood.

The need of the Aztecs to supply Huitzilopochtli chimes well with their own imperial ambitions. As they extend their empire, they gather in more captives for the sacrifice. As the sacrifices become more numerous and more frequent, there is an ever-growing need for war. And reports of the blood-drenched ceremonies strike terror into the enemy hearts required for sacrifice.

A temple at the top of a great pyramid at Tenochtitlan (now an archaeological site in Mexico City) is the location for the sacrifices. When the pyramid is enlarged in 1487, the ceremony of re-dedication involves so much bloodshed that the line of victims stretches far out of the city and the slaughter lasts four days. The god favours the hearts, which are torn from the bodies as his offering.

Festivals and sacrifice are almost continuous in the Aztec ceremonial year. Many other gods, in addition to Huitzilopochtli, have their share of the victims.

Each February children are sacrificed to maize gods on the mountain tops. In March prisoners fight to the death in gladiatorial contests, after which priests dress up in their skins. In April a maize goddess receives her share of children. In June there are sacrifices to the salt goddess. And so it goes on. It has been calculated that the annual harvest of victims, mainly to Huitzilopochtli, rises from about 10,000 a year to a figure closer to 50,000 shortly before the arrival of the Spaniards.

The most important gods, apart from Huitzilopochtli, are the rain god Tlaloc (who has a temple beside Huitzilopochtli’s on top of the great pyramid in Tenochtitlan) and Quetzalcoatl, god of fertility and the arts.

Quetzalcoatl: 10th – 16th century

Human sacrifice plays relatively little part in the cult of Quetzalcoatl, but the god himself has an extraordinary role in American history. The reason is that he merges in Aztec legend with a historical figure from the Mesoamerican past.

A Toltec king, the founder of Tula in about 950, is a priest of Quetzalcoatl and becomes known by the god’s name. This king, described as fair-skinned and bearded, is exiled by his enemies; but he vows that he will return in the year ‘One Reed’ of the 52-year calendar cycle. In 1519, a ‘One Reed’ year, a fair-skinned stranger lands on the east coast. The Aztecs welcome him as Quetzalcoatl. He is the Spanish conquistador Cortes.

Cortes advances into Mexico: 1519

Cortes reaches the coast of Mexico, in March 1519, with eleven ships. They carry some 600 men, 16 horses and about 20 guns of various sizes. The Spanish party is soon confronted by a large number of Indians in a battle where the effect of horses and guns (both new to the Indians) is rapidly decisive. Peace is made and presents exchanged – including twenty Indian women for the Spaniards. One of them, known to the Spaniards as Doña Marina, becomes Cortes’ mistress and interpreter.

Cortes then sails further along the coast and founds a settlement at Veracruz, leaving some of his party to defend it.

Before proceeding inland, Cortes makes a bold gesture. He sinks ten of his ships, claiming that they are worm-eaten and dangerous. The single surviving vessel is offered to any of his soldiers (and now sailors too, about 100 in all, liberated from their previous duties) who would prefer to return immediately to Cuba, publicly admitting that they have no stomach for the great task ahead. No one takes him up.

His small party is now irretrievably committed to the success of the adventure. Cortes leads them into the interior of the country.

The next battles, far more dangerous than the first encounters on the coast, are with the Tlaxcala people. The Spaniards eventually defeat them, and are received as conquerors in their capital city. This is a victory of great significance in the unfolding story, for the Tlaxcaltecs are in a state of permanent warfare with their dangerous neighbours. Any enemy of the Aztecs is a friend of theirs. They become, and remain, loyal allies of the Spaniards in Mexico.

In November 1519 when Cortes approaches Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztecs, his small force is augmented by 1000 Tlaxtalecs. But to the astonishment of the Spaniards, no force is needed.

Cortes and Montezuma: 1519-1520

The Aztec emperor, Montezuma II, has had plenty of warning of the arrival of the fair-skinned bearded strangers. He also knows that this is a One-Reed year in the Mexican calendar cycle, when the fair-skinned bearded Quetzalcoatl will at some time return.

The Aztec emperor, Montezuma II, has had plenty of warning of the arrival of the fair-skinned bearded strangers. He also knows that this is a One-Reed year in the Mexican calendar cycle, when the fair-skinned bearded Quetzalcoatl will at some time return.

He sends the approaching Spaniards a succession of embassies, offering rich gifts if they will turn back. When these fail, he decides against opposing the intruders with force. Instead Cortes is greeted in Tenochtitlan, on 8 November 1519, with the courtesy due to Quetzalcoatl or his emissary. In the words of one of the small band of conquistadors, they seemed to have Luck on their side.

For a week Cortes and his companions enjoy the hospitality of the emperor. They sit in his hall of audience and attempt to convert him to Christianity. They clatter round his city on their horses, in full armour, to see the sights (they are particularly shocked by the slab for human sacrifice and the newly extracted hearts at the top of the temple pyramid).

But Cortes is well aware of the extreme danger of the situation. He devises a plan by which the emperor will be removed from his own palace and transferred to the building where the Spaniards are lodged.

The capture of the emperor is carried out with a brilliantly controlled blend of persuasion and threat. The result is that Montezuma appears to maintain his full court procedure under Spanish protection. A few hundred Spaniards have taken control of the mighty Aztec empire.

During the next year, 1520, chaos and upheaval result from the approach of a rival Spanish expedition, launched from Cuba to deprive Cortes of his spoils. He is able to defeat it, but at a high price. In his absence the 80 Spaniards left in Tenochtitlan lose control of the city – largely thanks to their own barbarous treatment of the inhabitants.

When Cortes returns, he finds garrison and emperor besieged together. He persuades Montezuma to address his people from a turret, urging peace. The hail of missiles greeting this attempt leaves the emperor mortally wounded.

The situation is now so desperate that Cortes withdraws his army from the city in haste, in July 1520, during ‘the Sorrowful Night’. With Tlaxcala assistance he captures it again a year later, on 13 August 1521. There is no further Aztec resistance. The conquest of central Mexico is complete.

A brutal end: 1521-1533

The destruction by the Spaniards of the great Inca empire in Peru, twelve years after the similar fate of the Aztecs, brings to an effective end nearly three millennia of indigenous civilization in America – though the Maya, hard to suppress in the Yucatan jungle, preserve for a while their own ways.

The Spanish destroy the precious artefacts of these cultures with an unprecedented thoroughness – mainly in their lust for gold and silver, but sometimes (as with Mayan manuscripts) as an ideological assault on paganism. The result is that there is relatively little to show now for these rich cultures and their highly skilled crafts. Only the great pyramid mounds of their temples stand today as gaunt witnesses of a vivid past.

Read more:http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/plaintexthistories.asp?historyid=aa12#ixzz4WRjd6oBp