Lets start with Language:

Answer: No. The people who claim this are trying to prove that American Indians arrived in the Americas very recently (see Could Native Americans be recent immigrants? and Are Native Americans a lost tribe of Israel?) I have seen many websites claiming to “prove” that Amerindian languages are descended from Semitic or Germanic languages. 90% of these websites are deliberately lying, making up nonexistant “Algonquian” words that resemble words from Semitic languages. A quick glance at a dictionary of the Amerindian language in question will reveal these websites for what they are. The other 10% are using linguistically unsound methods–searching two languages for any two vocabulary words that begin with the same letter, essentially, and presenting them as evidence. Using this method, English can be “proved” to descend from Japanese–English “mistake” sounds a little like Japanese “machigai”. In fact, if you randomly generate some vocabulary with a computer program, you will be able to find a few words with surface resemblance to any language you want. Real linguistic analysis requires dozens of vocabulary relationships which are regular and predictable, as well as similarities in phonology and syntax, to show that one language is related to another. Here’s a good website by a Welsh speaker explaining the substantial linguistic differences between Mandan and Welsh, for example, or a website by an Athabaskan linguist explaining the differences between Carrier and Celtic. No linguist has ever shown a relationship between any Amerindian language family and a Semitic, Germanic or Celtic language.

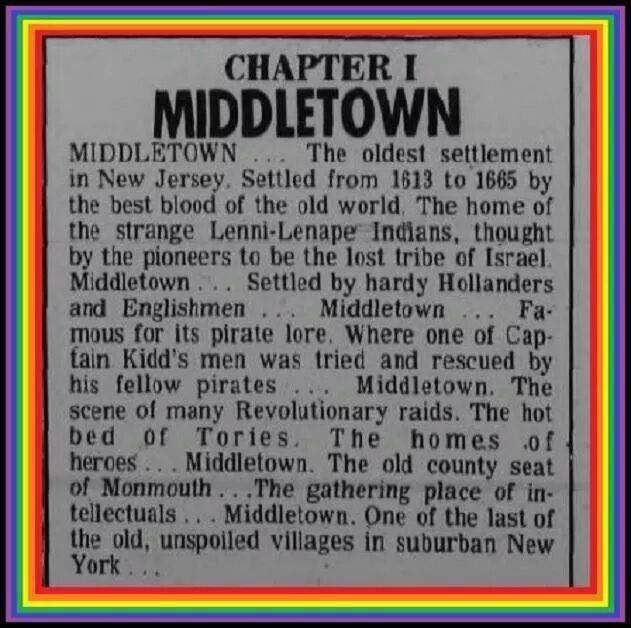

The Americans eventually relocated them to Oklahoma, where the modern Delaware Indian tribes are located today. Other Lenape people joined the Nanticoke or Munsee Delawares. There are also some small Lenne Lenape communities remaining in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The total Lenape population is around 16,000.

The Americans eventually relocated them to Oklahoma, where the modern Delaware Indian tribes are located today. Other Lenape people joined the Nanticoke or Munsee Delawares. There are also some small Lenne Lenape communities remaining in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The total Lenape population is around 16,000.THE TEN LOST TRIBES?

The idea of Native Americans being the lost tribes of Israel is based on the observance of the early settlers who wrote of accounts in their personal journals. This combined with the biblical narrative and a lack of education in linguistics produces circumstantial evidence that lead others to believe Native Americans are the lost tribes of Israel.

This old Monmouth of ours: History, tradition, biography, genealogy, and other anecdotes related to Monmouth County, New Jersey Hardcover – 1974

This Old Monmouth Of Ours [New Jersey]

Published by Polyanthos, Cottonport (1974)

About this Item: Polyanthos, Cottonport, 1974. Hardcover. Condition: fine. Reissue. One of 1000 numbered ccpies (of which this is copy No. 37) of the facsimile reissue, with a new introducton by Milton Rubincam. Hardcover. 444 pp. with index. Generally fine. Issued without dust jacket. Originally published in 1932, a collection of articles about Monmouth Cpunty, New Jersey that first appeared in The Freehold Transcript newspaper. Seller Inventory # GE16951

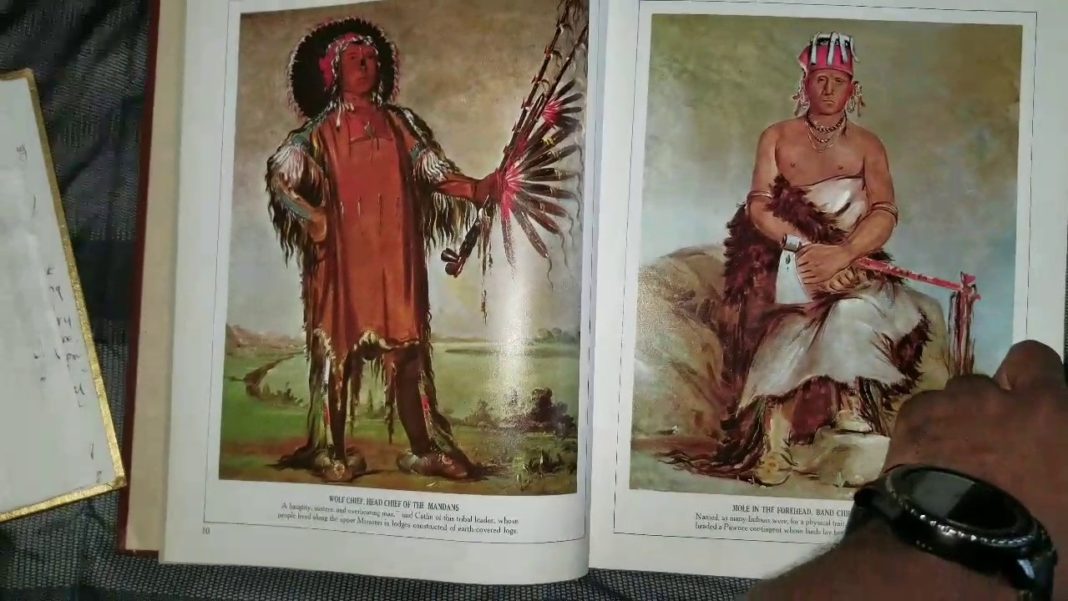

So as you see based on the dates of the 1st Colonial village founded in what would become Middletown New Jersey (1613 to 1665), the idea of Native Americans being the Lost tribes of Israel predate the works of James Adair. Adair’s career as an Indian trader and agent for South Carolina would make him worthy of historic attention, but it is his book that sets him apart from other notables of the day. By the time the work was published, he had developed it from an event-driven narrative designed to expose his political enemies and salvage his reputation into a complex examination of the origins of the American Indians. The book details important events between the 1740s and the 1770s and the central thesis, which dominates the text and has subsequently caused many to dismiss the contents, includes 23 arguments purporting to demonstrate that the American Indians are of Hebrew descent (the Lost Tribes of Israel). But as modern scholars have observed, while Adair’s central thesis is flawed, the evidence he presents and his sincere effort at comparative analysis of cultures has resulted in an astounding work on southeastern Indian culture, examining in detail such topics as gender roles, religion, warfare, marriage customs, and language. More importantly, Adair’s intense focus on matters of ritual purity has influenced the interpretative framework developed by modern anthropologists and ethnohistorians.

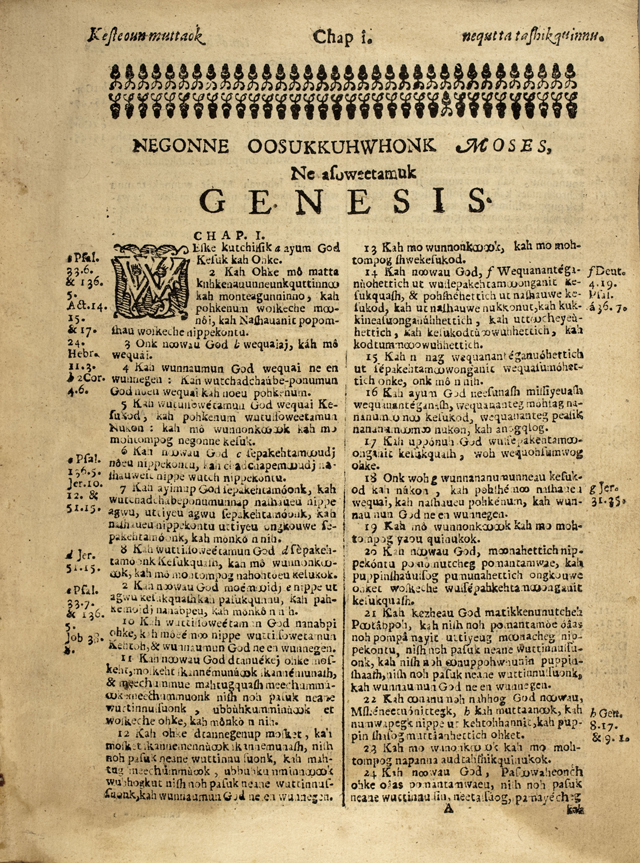

Prior to the Adair findings was the publishing of the Algonquin Bible.

The 1663 Eliot Bible:

The First Bible Printed in America

A leaf from John Eliot’s Algonquin (Native American “Indian” language) Bible. These leaves are three-and-a-half centuries old. Many people are shocked to discover that the first Bible printed in America was not English… or any other European language. In fact, English and European language Bibles would not be printed in America until a century later! Eliot’s Bible did much more than bring the Gospel to the pagan natives who were worshiping creation rather than the Creator… it gave them literacy, as they did not have a written language of their own until this Bible was printed for them.

The main reason why there were no English language Bibles printed in America until the late 1700’s, is because they were more cheaply and easily imported from England up until the embargo of the Revolutionary War. But the kind of Bible John Eliot needed for his missionary outreach to the native American “Indians” was certainly not to be found in England, or anywhere else. It had to be created on the spot. Eliot recognized that one of the main reasons why the native Americans were considered “primitive” by European settlers, is that they did not have a written alphabet of their own. They communicated almost exclusively through spoken language, and what little writing they did was in very limited pictorial images, more like Egyptian hieroglyphics than that of any functional alphabetical language like those of Europe or Asia or Africa.

Clearly the Word of God was something these people needed if they were to stop worshiping creation and false gods, and learn to worship the true Creator… but God’s Word could not realistically be translated effectively into their primitive pictorial drawings. So Eliot found a wonderful solution: he would give the native Americans the gift of God’s Word and also give them the gift of true literacy. He agreed to learn their spoken language, and they agreed to learn the Western world’s phonetic alphabet (how to pronounce words made up of character symbols like A, B, C, D, E, etc.) Eliot then translated the Bible into their native Algonquin tongue, phonetically using our alphabet! This way, the natives did not really even need to learn how to speak English, and they could still have a Bible that they could READ. In fact, they could go on to use their newly learned alphabet to write other books of their own, if they so desired, and build their culture as the other nations of the world had done. What a wonderful gift!

These Eliot Algonquin “Indian” Language Bible leaves remain one of the most rare and historically important artifacts of our American heritage. They are also among the earliest of all American printings, and the very first Bible printed in this hemisphere. Leaves from the Eliot Bible have sold for well over $3,000 each in recent months. We have fewer than a dozen leaves in stock. Each leaf comes with a beautiful Certificate of Authenticity. They measure approximately 7 to 8 inches tall by almost 6 inches wide, and they were printed on 100% rag cotton linen sheet, not wood-pulp paper like books today, so they remain in excellent condition… even after nearly 350 years. Each leaf is a unique piece of ancient artwork, carefully produced one-at-a-time, using a very rare early American movable-type press. Imagine… owning a leaf from the first Bible printed in the “New World”: The Eliot Bible.

So as you can see the efforts to civilize us aka christianize or even better romanize us had begun almost 100 years prior to the arrival of James Adair. All the evidence that points towards the Native Americans being the Lost Tribes is all circumstantial. With the exception of a few Cherokee Tribes that migrated from the Middle East, (ALL NATIVE AMERICANS NATIONS ARE NOT THE LOST TRIBES OF ISRAEL). We have village and mummified remains from here that predate the biblical narrative. And finally, NOT ONE NATIVE AMERICAN NATION CLAIMS TO BE DESCENDANTS OF THE LOST TRIBES OF ISRAEL.

Native Americans and Jews: The Lost Tribes Episode

In the 8th century BCE, the Assyrians dispersed the Kingdom of Israel, giving life and legend to the Lost Tribes. The repatriation of these lost tribes eventually became an integral part of the Jewish–and Christian–messianic dream, and there have been Lost Tribe speculations about numerous “discovered” populations. One the most fascinating — and unfortunately forgotten — such discussions centered on the Native Americans. How did American Jews respond to this? Why and how did Jews credit or discredit it? What did these theories signify about American Jewish agendas and anxieties?

A Theory is Born

One of the first books to suggest the Native American Lost Tribe theory was written by a Jew, the Dutch rabbi, scholar, and diplomat Manasseh ben Israel. In The Hope of Israel (1650), Ben Israel suggested that the discovery of the Native Americans, a surviving remnant of the Assyrian exile, was a sign heralding the messianic era. Just one year later, Thomas Thorowgood published his best seller Jewes in America, Or, Probabilities that those Indians are Judaical, made more probable by some Additionals to the former Conjectures. The Lost Tribe idea found favor among early American notables, including Cotton Mather (the influential English minister), Elias Boudinot (the New Jersey lawyer who was one of the leaders of the American Revolution), and the Quaker leader William Penn.

The notion was revived after James Adair, a 40-year veteran Indian trader and meticulous chronicler of the Israelitish features of Native American religion and social custom wrote The History of the American Indians…Containing an Account of their Origin, Language, Manners, Religion and Civil Customs in 1775. Even Epaphras Jones, an American Bible professor engaged the theory in 1831, claiming that anyone “conversant with the European Jews and the Aborigines of America… will perceive a great likeness in color, features, hair, aptness to cunning, dispositions for roving, &s.

Religious Connotations

Some of these writers were interested in Native American history, but most of them were just interested in the Bible. Indeed, the Lost Tribe claim should be seen as part of a general 19th-century fascination with biblical history. Explorations of Holy Land flora and fauna, the geography of the Holy Land, the life of Jesus-the-man, were very much en vogue. A close identification among some 17th and 18th century Americans with the chosen people of Scripture helped Christian settlers see their colonization of New England as a reenactment of Israel’s journey into the Promised Land.

It also contributed to a more general religious myth-making scheme that helped define the national identity of the United States. To cite just one example, in a 1799 Thanksgiving Day sermon, Abiel Tabbot told his congregation in Massachusetts:

“It has often been remarked that the people of the United States come nearer to a parallel with Ancient Israel, than any other nation upon the globe. Hence, ‘OUR AMERICAN ISRAEL,’ is a term frequently used; and common consent allows it apt and proper.”

A curious incident that drew considerable attention and “proved,” at least to some, that Native Americans had ancient Israelite origins unfolded when tefillin (phylacteries) were “discovered” in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in the early 19th century. Their discoverer wrote that this “forms another link in the evidence by which our Indians are identified with the ancient Jews, who were scattered upon the face of the globe, and to this day remain a living monument, to verify and establish the eternal truths of Scripture.”

Prominent Jews Respond

Around the time of the Pittsfield incident, Mordecai Manuel Noah, the journalist, playwright, politician, and Jewish American statesman, began spilling ink about the subject. Noah wrote a play She Would be a Soldier; or, The Plains of Chippewa (1819), that resolved the tension between the Yankees and the British by identifying the Indian Great Spirit with the God of the Bible. Noah’s ideas about Jewish-Native affinities grew in a distinctly political manner when he invited Natives Americans to help settle “Ararat,” the separatist Jewish colony he hoped to establish on Grand Island on the Niagara River around 1825.

Noah’s writings on Jewish Natives came to their full expression with his Discourse on the Evidences of the American Indians Being the Descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel (1837). The work documented a host of theological, linguistic, ritual, dietary, and political parallels between Jews and Native Americans. Most importantly, he identified several essential character traits shared by the two peoples, all of which were, of course, highly laudable. For Noah, the conflation of Indians and Jews sanctioned the latter as divinely ordained Americans.

Another notable Jewish-Indian incident occurred in 1860, when stones hewn with Hebrew inscriptions were found near Newark, Ohio. The story unfolded over the course of many months and was followed closely by The Israelite, The Occident, and The Jewish Messenger, whose respective editors represented the intellectual vanguard of American Jewry. Isaac Mayer Wise, the leader of the Reform movement in America, employed philological proofs to undermine the stone’s authenticity. He rejected any connections between Jews and Native Americans, though it’s notable that he bothered to engage the story at all. Isaac Leeser, a traditionalist, sided in favor of the Lost Tribes theory. Reviewing the relics in question, The Occident, Leeser’s newspaper, concluded, “The sons of Jacob were walking on the soil of Ohio many centuries before the birth of Columbus.”

Implications

From a historical and scientific point of view, the Native American Lost Tribe claim is clearly narishkeit (Yiddish for foolishness). But even a brief exploration of it — who was making it and why, who was refuting it and why, reveals important insights about American Jewry. Popular thought about who Jews were — their place in America, with whom they could or should be associated — helps us understand how Jews negotiated their place in American society. Theories about Ancient Israelite Indians should not be dismissed as mere fantasy. Rather they are important precisely because they are fantasy.

Jews responded to the Lost Tribes claim about Native Americans in sermons, plays, public statements, scholarly works, and popular writings. The critical responses are more understandable: from the perspective of Reform and science, the theory is flagrantly nonsensical. But there are other reasons some may have rejected it: so as not to be associated with that which was thought of as native, primitive, and barbarian, so as not to be thought of as atavistic or lower on the evolutionarily ladder than other Europeans, so as not to be thought of as imminently disappearing from history, and so as not to be in need of Christian civilizing (i.e. missionizing). Advocates, on the other hand, had to go against the scholarly consensus and side with religious figures who could be dismissed as fanatics.

Accepting Native Americans as ancient Israelites held several — sometimes mutually exclusive — implications for American Jews. Foremost, it meant that the Indians were, in some way, related. It could buttress the sentiment that America was the New Jerusalem. This was the destined place where the original exiles, scattered to unknown corners of the world, were ingathered to their God-chosen Promised Land. They were not “lost” at all. Rather, the near aboriginal connection of Jews to the American soil served as evidence of the end of exile, and another reason to support a new American Jewish identity.

Many of the major figures in 19th-century American Jewry weighed in–in one manner or another–on the Jewish-Indian controversy. The practical stakes were never high, but the claim — so ubiquitous and so fluid (since it was used for so many different functions by so many different people) — was taken seriously and fretted over by Jewish leaders of very different orientations. The Lost Tribe theory had significant symbolic stakes — for Jews, Christians and Native Americans. Linking America and its earliest inhabitants with the Bible and its theology, meant staking a claim on America–and championing God’s plan for the New World.

THIS WAS A CONVERSATION INTRODUCED AND THEORIZED BY YOUR OPPRESSORS, THE SAME OPPRESSORS WHO FOUND YOU HERE, LEARNED FROM YOU, AND THEN ENSLAVED YOU AND WROTE YOUR TRUE IDENTITY OUT OF HISTORY. WE ARE SELF DEFINING NATIONS WITH OUR OWN HISTORY AND LANGUAGES. RESPECT US FOR WHO WE ARE, NOT WHO YOU WANT US TO BE.

Native Americans and the Lost Tribes

An all-too forgotten historical debate BY DAVID KOFFMAN

“One of the first books to suggest the Native American Lost Tribe theory was written by a Jew, the Dutch rabbi, scholar, and diplomat Manasseh ben Israel. In The Hope of Israel (1650), Ben Israel suggested that the discovery of the Native Americans, a surviving remnant of the Assyrian exile, was a sign heralding the messianic era. Just one year later, Thomas Thorowgood published his best seller Jewes in America, Or, Probabilities that those Indians are Judaical, made more probable by some Additionals to the former Conjectures. The Lost Tribe idea found favor among early American notables, including Cotton Mather (the influential English minister), Elias Boudinot (the New Jersey lawyer who was one of the leaders of the American Revolution), and the Quaker leader William Penn.”

In his article Titled, “Does Bible Prophesy Book of Mormon?“, Gerald Sigal explores the Moran assertation that the Native Americans decent from the Lost Tribes.

“A main contention of Latter-day Saint theology is that the American Indians are the descendants of the Lamanites, that is, descendants of Lehi’s son Laman. According to the Book of Mormon, “Aminadi was a descendant of Nephi, who was the son of Lehi, who came out of the land of Jerusalem, who was a descendant of Manasseh, who was the son of Joseph, who was sold into Egypt by the hands of his brothers” (Alma 10:3). Since the Book of Mormon claims that this individual, Lehi, was an Israelite the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints claims that the American Indians are of Israelite origin. Specifically, Latter-day Saint doctrine teaches that they are descendants of the tribe of Manasseh, son of Joseph. This claim is extensive in Latter-day Saint literature. If the American Indians are not possibly of Israelite extraction, the entire story of Lehi and his family’s journey to America in the time of Zedekiah is shown to be spurious.”

Sigal Also notes that the end of his article that “There is no genetic, linguistic, or cultural evidence to substantiate this claim that the Mongoloid native American Indians are descended from Semitic Israelites.”

The Bottom Line

Jewish tradition tells us that at the end of times, the Messianic Era, all the tribes will be reunited in Israel. And say to them, So says the Lord God: Behold I will take the children of Israel from among the nations where they have gone, and I will gather them from every side, and I will bring them to their land.

– Ezekiel Chapter 37. 21

“And it will be on that day a great shofar will be blown, and those that are lost in Assyria and cast away in the land of Egypt will come and bow to G‑d at the Holy Mount in Jerusalem.” (Isaiah 27:13)

So there you have it, Judaism 101.