|

|

Indian Place Names in New JerseyThe following information is from the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration 1938-1939 Series, Bulletin 12.

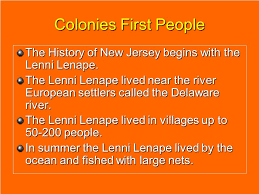

The Lenape language, like the people, was very simple. It was made up of words which expressed things rather than ideas. A name for an animal or place was in itself a description of the thing it identified. When the Lenape used his word for horse, he was really saying “four footed animal carries on back;” to him cow was “animal walking on flat split hoof.” For their writing symbols the Indians of New Jersey used small pictures. The history of their nation is recorded on a series of pictographs, known as the Walam Olum (red-painted record). This record was cut into wood, and its symbols were traced with red. Each subtribe of the Lenape kept its own Walam Olum, but all the records began by describing how the great Manito (god) made the sea, the sky and the earth, and created man and the animals. All was well until an evil spirit, a huge serpent, sent a flood over the earth. Everyone perished except the ancestors of the Lenape. They were lifted up on the back of the turtle, and the turtle carried them to dry land. The record tells further that the Lenape wandered toward the rising sun. They came upon a great river (probably the Mississippi), crossed it, and after many generations reached what we call New Jersey. The Walam Olum was translated by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, a professor in Transylvania University, Kentucky. He began his research early in the 19th century and after many years completed the double translation of the pictures into the Indian language, and the Lenape sounds into their English meanings. There were a number of Lenape subtribes scattered throughout the State. One of these the Unami (the fishing-people), were highly regarded because their totem, tattooed on their breasts, was the sign of the sacred turtle. This device marked them as the direct descendants of the people whom the turtle had lifted out of the flood. They lived in the central New Jersey region. Another tribe living in South Jersey was the Unilachtigo; their totem sign was the turkey. Also there were the Minsi (people of the stony country), the wolf people, who lived in the north Jersey hills. The Minisink trail, which led from the mountains to the seacoast, was named for these people. Chatham in Morris County, where the trail crossed the Passaic River, was known in Colonial days as Minisink Crossing. Minisink Island in the Delaware River marks the point where the trail crossed and entered the Kittatinny Mountains. In many places throughout the State automobile highways follow the route of this ancient Indian path. Another subtribe of the Lenape were the Mantuas, whose totem was the frog. Some authorities believe that Mantoloking, a seaside fishing resort in Ocean County, was named for them. These subtribes were dived into many small kingdoms of families. One of these, the Matavancons, lived in what is now Monmouth County. There were fishermen and, it is said, lived on the stream which now bears a part of their name, Matawan Creek. The town of Matawan, some authorities believe, stands near what was the site of their village. Old Millstone, in Somerset County, was once known as Matawank and probably got its name from the same people. The Lenape called themselves “Men among Men” or Leni Lenape. Some of their relatives among other Indians recognized their wisdom and experience by calling them Grandfathers. But their enemies, the Iroquois or Six Nations, gave them the name “Women Mohegans” after they had persuaded the Lenape to become peacemakers in a dispute. Peacemaking, according to custom before that time, had been the duty only of women. Nomahegan Brook in Union County drew its name from this Iroquois title, Noluns Mohegans, which appeared in a treaty with the Indians made by the governors of New Jersey and Pennsylvania in 1758. Memories of Lenape chiefs have been preserved in the names of some places. Local historians say the Nihomus Run in Salem County bears the name of an Indian who signed the deed of land purchased by the Quakers under John Fenwick’s leadership in 1675. NA-MAHOMIS, meaning “my grandfather,” was a title of respect frequently used by the New Jersey Lenape and probably was shortened into Nihomus by the white men. Most famous of all the Lenape chiefs was Tamanend, twisted into Tammany by the white man, who gave his name to Mount Tammany on the New Jersey side of the Delaware Water Gap. This name means “beaverlike” or “amiable” to the Indians. Tamanend, who sold land to William Penn, owner of much of West New Jersey, was the third Lenape chief of that name. The Walam Olum says of him: “He was good, this affable one, and came as the friend of all the Lenape.” Oratam, a sachem of the Hackensack Indians, who fought and then made lasting peace with the Dutch, has given his name to several localities and organizations in Bergen County. A good example of the difficulty in tracing present day names to their Indian origin is Hackensack, now the name of a river and a county seat. The name is supposed to derive from Achkincheschakey (A-kin-hes-kakee). The old-time map makers spelled this difficult name in many ways; their versions range all the way from Hockquindachque to Hocquaansauk. Students of the Indian language who based their translations on certain of the incorrect spellings have claimed that the name meant “hook-shaped mouth,” or “land of big snakes,” or “country full of snakes;” one interpretation is that the river was named for a tribesman called Hackquin-Sacq. Careful study has disclosed, however, that the original name Achikincheschakey meant “stream which discharges itself into another on the level ground.” Lamington, the name of a river which is part of the boundary between Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, and also the name of a town, was originally Allmatunk, and meant “river under hill.” Raritan, the name of one of New Jersey’s largest rivers, was twisted from the original Naraticong, a place where a family of the Lenape lived and which suggests “river behind the island.” Many place names have come from the Indian words for birds or animals. Several points along the eastern New Jersey water front are named for water fowl: Absecon, near Atlantic City, means “place of swans;” Weehawken was the red man’s name for “place of gulls.” The reason for naming some places from the Indian’s names of animals are not so easily traced. Moonachie, the place in Bergen County where the Iroquois came to collect tribute from the Lenape, come from the word for “ground hog;” Secaucus was originally Ac-Coke (black snake). The town of Whippany was first called Whippinong by the Lenape, for in that neighborhood grew viburnum trees which furnished the red men with materials for their barbed shafts: Whippinong means “place of the arrowwood.” Peapack, a town in central New Jersey, also bears an Indian title associated with plants; it means “water roots.” Hohokus in Bergen County in its original form, Nehohokus, meant that many red cedar trees grew in the vicinity. Another tree is commemorated by the Indian name Wanaque, in Passaic County; the meaning is “land of sassafras,” from the root of which the Lenape made medicine. The community of Metuchen derives its name from the Indian word for “dry firewood.” The cranberry, native of New Jersey for untold centuries, is remembered in Peckman Brook, Essex County, once Peckamin River, from the Indian name of the cranberry. Tuckahoe in Cape May County is a reminder that the first white settlers were obliged at times to eat Indian food while waiting for crops. The name was applied by the Algonquin Nation, of which the Lenape were a part, to bulbous roots which they ate. One was Indian turnip, or Jack-in-the-pulpit; another, golden club, a water root; and a third, arrow arum, which had an arrow-shaped leaf. Tuckahoe also included a fungus growing underground, which the white man spoke of as Indian loaf or Indian bread. All these are still to be found. People in Eastern Virginia today are nicknamed Tuckahoe, probably because this Indian food saved the settlers there under Capt. John Smith from starving. Two villages in New York State also bear the name of Tuckahoe. Many Indian names described watercourses: Communipaw means “landing place from other side of the river.” The Jersey Central Railroad ferry to New York is there now. Saconk, old name of Blue Brook near New Providence, means “outlet of a stream.” Totowa (the falls between river and mountain) refers to the Falls of the Passaic River. Assanpink, in the red man’s language, means “stony creek.” The small streams in Trenton by this name was the site of a decisive battle during the Revolution, frequently referred to as the second Battle of Trenton, January 2, 1776. Watsessing, the name of a part of Bloomfield, authorities once believed, was also associated with a stream, and its meaning was given as “crooked water,” although further research indicates that it translates into “stony hill.” On Long Beach Island the surf gives its name to Peahala, translated “rushing water.” Frequently the names the Indians used to describe the formation or peculiar characteristics of the land were adopted by the white men. Succasunna in Morris County means “land of black stones.” This probably was the Indians’ way of describing the iron ore found in that region. Another name describing the nature of the land is Navesink near Sandy Hook, which translates to “where land goes to a point.” Still another name descriptive of a geographical feature is Passaic, the only New Jersey county name of Indian derivation, and also the name of a river and a city. It means “valley.” But the modern Passaic Valley, in which today are large towns and a dozen broad highways, not even remotely resembles the peaceful region the red men knew. Scheyichbi has vanished, and with it the Lenape. Only the names they gave to our map makers—twisted, shortened, meaning and accent nearly forgotten—remain to remind us of a time when our State was the home of a proud people, a race lifted above the wrath of the waters on the back of a tortoise. The following glossary, while not all inclusive, gives an idea of the various meanings of Indian derived words. GLOSSARY

From “Bridging the Years in Denville” by C.M. toeLaer From an old hand written ledger done by J.P. Crayon of Union Hill the meaning of many Indian names in this vicinity are given.

|

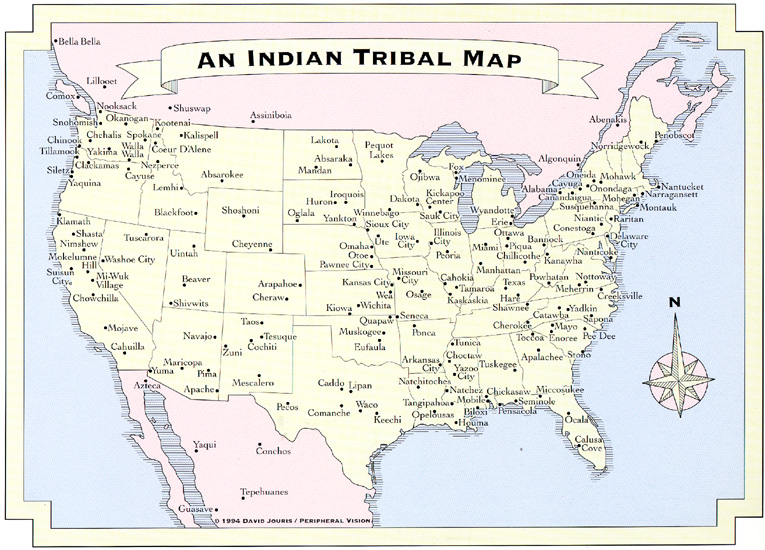

The highly industrialized State of New Jersey bears little resemblance to the land that the Lenape, its first proprietors, called Scheyichbi. Throughout the State are towns, lakes, rivers and mountains, whose names recall the primitive people who were the first to make this part of the world their own. As the white men explored and took possession of the land, they frequently adopted the names used by the Indians to describe land sites, rivers, lakes and other places. Sometimes the cumbersome Indian name would be shortened or twisted to suit the white man’s tongue so that the present day form of the word is not always easy to trace back.

The highly industrialized State of New Jersey bears little resemblance to the land that the Lenape, its first proprietors, called Scheyichbi. Throughout the State are towns, lakes, rivers and mountains, whose names recall the primitive people who were the first to make this part of the world their own. As the white men explored and took possession of the land, they frequently adopted the names used by the Indians to describe land sites, rivers, lakes and other places. Sometimes the cumbersome Indian name would be shortened or twisted to suit the white man’s tongue so that the present day form of the word is not always easy to trace back.