Goodbye Uncle Tom

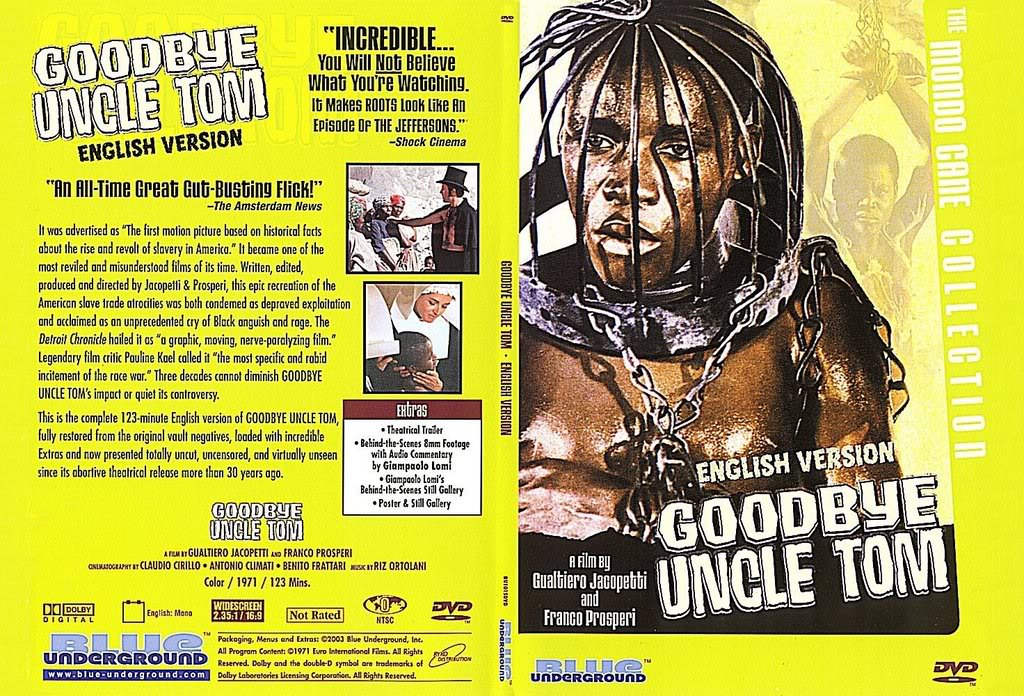

Farewell, Uncle Tom / Addio Zio Tom Gualtiero Jacopetti & Franco Prosperi Italy, 1971

Review byDavid Carter

A still from Goodbye Uncle Tom adorns the front cover of Mark Goodall’s examination of Mondo cinema Sweet & Savage. The scene in question shows three white men, rifles on their hips, posed for a photo next to a large pile of dead black men. The whites are slave hunters—the blacks, their quarry. The camera flashes. The “dead” slaves spring to life and run laughing into the surrounding brush, the trio of hunters following slowly behind, content that their charade will placate their benefactors. For the whites, truth has become malleable. They know that the visual image is more valuable than the lives of those in it; shooting with the camera what they once would have shot with their guns. They have created an authentic scenario but one that is in reality mere smoke and mirrors, a new “truth” constructed out of clever fictions. Nowhere else in the film are Jacopetti and Prosperi’s intentions more unmistakably or brilliantly communicated.

A still from Goodbye Uncle Tom adorns the front cover of Mark Goodall’s examination of Mondo cinema Sweet & Savage. The scene in question shows three white men, rifles on their hips, posed for a photo next to a large pile of dead black men. The whites are slave hunters—the blacks, their quarry. The camera flashes. The “dead” slaves spring to life and run laughing into the surrounding brush, the trio of hunters following slowly behind, content that their charade will placate their benefactors. For the whites, truth has become malleable. They know that the visual image is more valuable than the lives of those in it; shooting with the camera what they once would have shot with their guns. They have created an authentic scenario but one that is in reality mere smoke and mirrors, a new “truth” constructed out of clever fictions. Nowhere else in the film are Jacopetti and Prosperi’s intentions more unmistakably or brilliantly communicated.

Jacopetti and Prosperi’s fifth film is perhaps their most challenging. It was, however, a logical next step following Africa Addio, a film rich with both the most poignant and exploitive aspects of the genre (and arguably its zenith at the point). With Mondo Cane, et al., the pair had not only contributed to the world of documentary filmmaking but also created a completely new way of analyzing the world, a new “reality” that could be shaped in the same manner a journalist constructs prose. Jacopetti and Prosperi had moved beyond shaping their version of the modern world, however. The pair had deceptively framed authentic scenes and created others whole cloth. Their manipulations of truth took many forms, some benignly playful, others potentially criminal. Misleading narration occasionally obscures details such as time and place throughout their first four films. Expertly deconstructed by Kerekes and Slater in Killing for Culture, the self-immolation sequence from Mondo Cane 2was a fabrication. Africa Addio sparked a government inquiry due to claims that the filmmakers had staged the real-life executions of rebels to be more conducive to filming. Nothing within the context of these films separates the fake material from the authentic. Having effectively and lastingly blurred the line between reality and fabrication, it became necessary for them to completely destroy it. Thus Goodbye Uncle Tom.

As the film opens, a sentimental ballad rises on the soundtrack and a helicopter descends on a southern plantation—almost immediately it is evident that this is not the present day but a century prior. The viewpoint encroaches on the plantation as two well-dressed slaves pull back the doors to an exquisite parlor. The men behind the camera are introduced to the guests as Italian journalists (Jacopetti and Prosperi, though unnamed) arranging an inquest into slavery. As the personages around the table are introduced, each sharing their personal take on Catholicism, Europe, and, most importantly, slavery, Jacopetti and Prosperi’s central device becomes clear: real people and real ideas in a manufactured setting. Historical reality as documentary fiction—historical fiction as documentary reality. One of the film’s rare instances of voice-over narration, provided by the filmmakers themselves (and not the glib, third party that is common to Mondo films), reaffirms this moments later. The choice is the first of many deconstructions of the Mondo cinema aesthetic Jacopetti and Prosperi established in their earlier films.

What follows are historically accurate recreations of the treatment of slaves from their arrival on overpopulated cargo boats to their lives on plantations. The narrator occasionally provides passages from historical documents to confirm the accuracy of the on-screen occurrences, which depict the harsh realities of the slave trade. These scenes most often feel sensationalized and exploitive, however, which is perhaps the overarching theme of Jacopetti and Prosperi’s body of work. The clich√É© that “truth is stranger than fiction” does not accurately describe the concept at work here. Mondo Cane reported on the cultural mores of various societies but limited itself to those activities that would shock or titillate. The film’s success demonstrated that documentary cinema could captivate an audience provided it dealt with the salacious aspects of reality. This concept – reality as visual taboo – is as old as man himself, and a particularly important part of the history of cinema. Mondo cinema, as cultivated by Jacopetti and Prosperi, presents visual taboos (and therefore reality) as entertainment. These taboos had previously been presented in short, easily digestible segments with comic undertones in Mondo Cane and its sequel to allow viewers the thrill of transgression while giving them the ability to remain detached—and therefore safe. Goodbye Uncle Tom provides no such safety for its audience.

Being that the taboos depicted in it are usually the stuff of exploitation films, Goodbye Uncle Tom is often accused of being categorically exploitative. This claim is not entirely without merit, but it represses the film’s more high-minded goals. All of the “mysteries of life” (birth, death, sex – including homosexuality and pedophilia – and bodily functions) are herein presented without inhibition, and these images assault the viewer. Goodbye Uncle Tomstrips away the expository narration of documentary cinema and the narrative justifications of scripted cinema, effectively leaving the viewer to comprehend these images without familiarly conventional means of detachment. It is a smoother variant of the disorienting “shock cut” from Mondo Cane; rather than jumping from the innocuous to the disturbing, Goodbye Uncle Tom strengthens these images by making them more “real” via the removal of the safeguards (comic relief, brevity) of their earlier works.

The revulsion induced by the film’s visual aspect is only surpassed by Jacopetti and Prosperi’s most devious technique: allowing the personages in the film to speak for themselves. Mondo Cane left us to imagine what the practitioners of strange activities were thinking and to generally assume that they were ignorant of how bizarre or immoral their behavior was. Goodbye Uncle Tom again moves away from its predecessors by supplementing the visual observations with direct interviews. Though historically accurate and occasionally quoted directly, Jacopetti and Prosperi knew that modern viewers would find the words of these subjects either laughable or (most often) detestable. Nowhere is this more true than in one of the film’s longest sequences in which a professor shares his scientific theories on the inferiority of Africans, and describes the barbaric methods he uses to study and “treat” them. By allowing the man to voice his beliefs, his practices seem all the more atrocious because they are not mere mindless cruelty but rather the product of a calculating yet flawed logic. The questions posed by the unseen journalists heighten the effectiveness of this particular scene.

This technique (intentionally?) falters at two key points in the film when the filmmakers have personal interactions with two slaves, and both instances are employed to further deconstruct the Mondo aesthetic. The first scene sees them almost succumb to the temptation of an underage black prostitute, while the second shows them get into a heated argument with an intelligent slave who touts the benefits of slavery. Their temptation by the young girl reveals them to be human, effectively destroying the “God” of the documentary format. By acknowledging their temptation, the filmmakers deny themselves objectivity. They are no longer merely observing events but participating in them, bringing into question their culpability since at no point they attempt to stop anything that’s happening.

The latter scene destroys the remaining vestiges of both Mondo aesthetic and documentary integrity. Once it becomes evident that the opinions of a particular slave contradict those held by the filmmakers, they make a hasty retreat while hurling barbs at their subject. His opinion creates a counterargument to theirs, and they want no part of it. The reality that they’ve imposed upon their subjects and the audience is now imposed upon them. The filmmakers are revealed to be subjective in presenting their film’s truths, effectively manipulating the very world presented to their audience. The viewer implicitly knows this manipulation is taking place, yet this revelation, given the film’s pretensions toward documentary reality, is as subversive and disturbing as any of the many transgressive images.

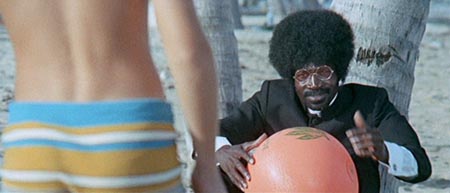

In a film known for its confrontational nature, there is no element more controversial than the conclusion. Goodbye Uncle Tom travels to the modern day (1971, at the time), centering on a black militant as white people frolicking on the beach interrupt his reading of Nat Turner’s diaries. He becomes immersed in the work despite the distractions, vividly imagining both Nat Turner’s actions and his own violent revolution. Whether or not the modern uprisings are real is left ambiguous, although the overly symbolic nature of these sequences seemingly places them in the realm of fantasy. The scenes are an impressively powerful conclusion. The depiction of a black uprising against whites would have no doubt chilled audiences in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement of the sixties, but the conclusion is more a catharsis for the previous scenes than an exploitative jab. Jacopetti and Prosperi’s Mondo films viewed the world as an ultimately binary system: civilized/uncivilized, cause/effect. By having the horrors of slavery “paid back” to the whites, the binary loop is closed for the filmmakers and the viewers alike, allowing cinematic closure for a historical period that lacks one.

By abandoning their Mondo cycle, Jacopetti and Prosperi created one of cinema’s most challenging and complex works. It is one that has been largely ignored by film academics, usually only garnering a mention for what is seen as its “exploitive” content. This could possibly be due to the fact that, as with slavery itself, Goodbye Uncle Tom is a difficult subject to discuss, as it examples worst aspects of human nature, and forces us face the discomforting contents head on. Jacopetti and Prosperi have been praised for their stylish and influential documentaries, but Goodbye Uncle Tom is perhaps their greatest achievement—if nothing else, an incendiary cinematic experience that has yet to be equaled.

By David Carter