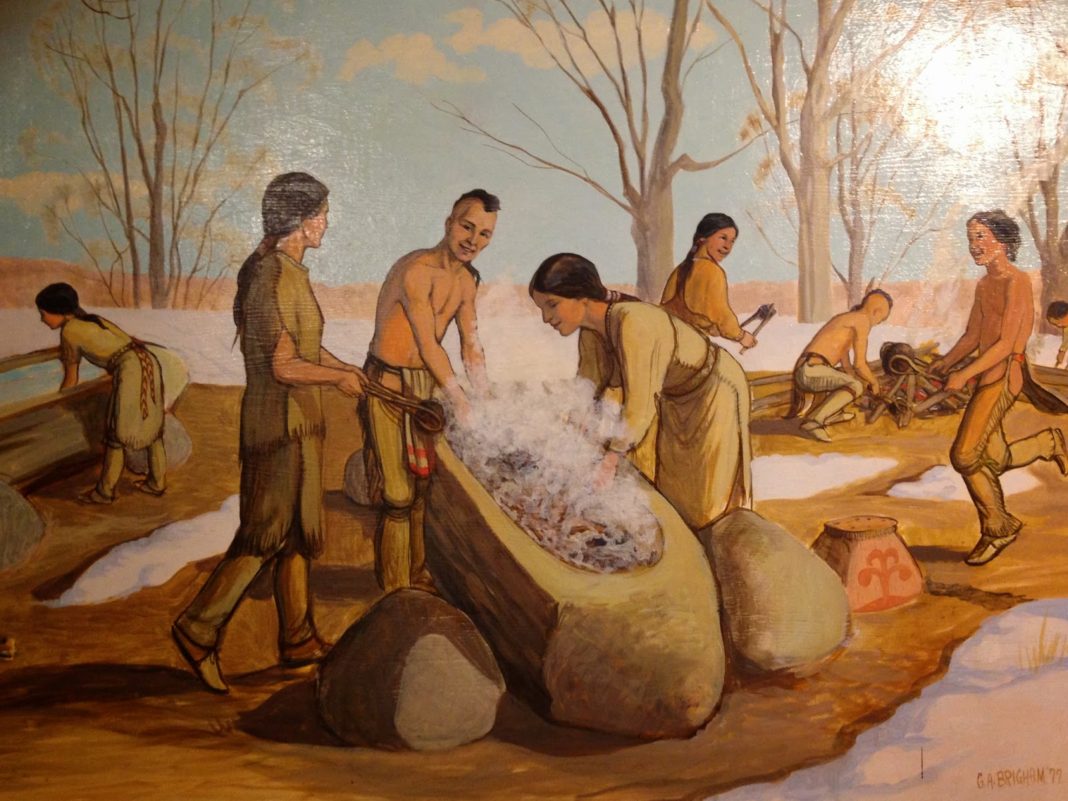

Native Americans were using maple sugar as a sweetener long before the pilgrims set foot on North America. The Indians traded the maple sugar with the colonists, who, in turn, learned how to make the sweet treat from the Native Americans.

Maple sugar was the predominant way to sweeten things up in America until the 1800s, when the sugar cane industry started in the Caribbean. In the early days sugar cane was expensive, especially to those in the northeast living far from the tropical waters of the Caribbean islands. But today sugar is cheap, and maple sugar and maple syrup have become specialty items–tasty ones at that!

https://themainehighlands.com/story/maine-maple-syrup/vtm497BFBE08AF349A0E

Indian Slavery in the Americas

Indian Slavery in the Americas

The story of European colonialism in the Americas and its victimization of Africans and Indians follows a central paradigm in most textbooks. The African “role” encompasses the transportation, exploitation, and suffering of many millions in New World slavery, while Indians are described in terms of their succumbing in large numbers to disease, with the survivors facing dispossession of their land. This paradigm—a basic one in the history of colonialism—omits a crucial aspect of the story: the indigenous peoples of the Americas were enslaved in large numbers. This exclusion distorts not only what happened to American Indians under colonialism, but also points to the need for a reassessment of the foundation and nature of European overseas expansion.Without slavery, slave trading, and other forms of unfree labor, European colonization would have remained extremely limited in the New World. The Spanish were almost totally dependent on Indian labor in most of their colonies, and even where unfree labor did not predominate, as in the New England colonies, colonial production was geared toward supporting the slave plantation complex of the West Indies. Thus, we must take a closer look at the scope of unfree labor—the central means by which Europeans generated the wealth that fostered the growth of colonies.

Modern perceptions of early modern slavery associate the institution almost solely with Africans and their descendants. Yet slavery was a ubiquitous institution in the early modern world. Africans, Asians, Europeans, and Native Americans kept slaves before and after Columbus reached America. Enslavement meant a denial of freedom for the enslaved, but slavery varied greatly from place to place, as did the lives of slaves. The life of a genizaro (slave soldier) of the Ottoman Empire, who enjoyed numerous privileges and benefits, immensely differed from an American Indian who worked in the silver mines of Peru or an African who produced sugar cane in Barbados. People could be kept as slaves for religious purposes (Aztecs and Pacific Northwest Indians) or as a by-product of warfare, where they made little contribution to the economy or basic social structure (Eastern Woodlands). In other societies, slaves were central to the economy. In many areas of West Africa, for instance, slaves were the predominant form of property and the main producers of wealth.

As it expanded under European colonialism to the New World in the late fifteenth through nineteenth centuries, slavery took on a new, racialized form involving the movement of millions of peoples from one continent to another based on skin color, and the creation of a vast slave-plantation complex that was an important cog in the modernization and globalization of the world economy. Africans provided the bulk of labor in this new system of slavery, but American Indians were compelled to labor in large numbers as well.

In the wake of the deaths of indigenous Americans from European-conveyed microbes from which they had no immunity, the Spanish colonists turned to importing Africans. A racist and gross misinterpretation of this event posited that most Indians could not be enslaved because of their love for freedom, while Africans were used to having their labor controlled by “big men” in Africa. This dangerous view obscured a basic fact of early modern history: Anyone could be enslaved. Over a million Europeans were held as slaves from the 1530s through the 1780s in Africa, and hundreds of thousands were kept as slaves by the Ottomans in eastern Europe and Asia. (John Smith, for instance, had been a slave of the Ottomans before he obtained freedom and helped colonize Virginia.) In 1650, more English were enslaved in Africa than Africans enslaved in English colonies. Even as late as the early nineteenth century, United States citizens were enslaved in North Africa. As the pro-slavery ideologue George Fitzhugh noted in his book, Cannibals All (1857), in the history of world slavery, Europeans were commonly the ones held as slaves, and the enslavement of Africans was a relatively new historical development. Not until the eighteenth century did the words “slave” and “African” become nearly synonymous in the minds of Europeans and Euro-Americans.

With labor at a premium in the colonial American economy, there was no shortage of people seeking to purchase slaves. Both before and during African enslavement in the Americas, American Indians were forced to labor as slaves and in various other forms of unfree servitude. They worked in mines, on plantations, as apprentices for artisans, and as domestics—just like African slaves and European indentured servants. As with Africans shipped to America, Indians were transported from their natal communities to labor elsewhere as slaves. Many Indians from Central America were shipped to the West Indies, also a common destination for Indians transported out of Charleston, South Carolina, and Boston, Massachusetts. Many other Indians were moved hundreds or thousands of miles within the Americas. Sioux Indians from the Minnesota region could be found enslaved in Quebec, and Choctaws from Mississippi in New England. A longstanding line of transportation of Indian slaves led from modern-day Utah and Colorado south into Mexico.

The European trade in American Indians was initiated by Columbus in 1493. Needing money to pay for his New World expeditions, he shipped Indians to Spain, where there already existed slave markets dealing in the buying and selling of Africans. Within a few decades, the Spanish expanded the slave trade in American Indians from the island of Hispaniola to Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba, and the Bahamas. The great decline in the indigenous island populations which largely owed to disease, slaving, and warfare, led the Spanish to then raid Indian communities in Central America and many of the islands just off the continent, such as Curacao, Trinidad, and Aruba. About 650,000 Indians in coastal Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Honduras were enslaved in the sixteenth century. Conquistadors then entered the inland American continents and continued the process. Hernando de Soto, for instance, brought with him iron implements to enslave the people of La Florida on his infamous expedition through the American southeast into the Carolinas and west to the Mississippi Valley. Indians were used by the conquistadors as tamemes to carry their goods on these distant forays. Another form of Spanish enslavement of Indians in the Americas was yanaconaje, which was similar to European serfdom, whereby Indians were tied to specific lands to labor rather than lords. And under the encomienda system, Indians were forced to labor or pay tribute to an encomendero, who, in exchange, was supposed to provide protection and conversion to Christianity. The encomenderos’ power survived longest in frontier areas, particularly in Venezuela, Chile, Paraguay, and in the Mexican Yucatan into the nineteenth century.

By 1542 the Spanish had outlawed outright enslavement of some, but not all, Indians. People labeled cannibals could still be enslaved, as could Indians purchased from other Europeans or from Indians. The Spanish also created new forms of servitude for Indians. This usually involved compelling mission Indians to labor for a period of time each year that varied from weeks to months with little or no pay. Repartimiento, as it was called, was widespread in Peru and Mexico, though it faded quickly in the latter. It persisted for hundreds of years as the main system for organizing Indian labor in Colombia, Ecuador, and Florida, and survived into the early 1820s in Peru and Bolivia. Indian laborers worked in the silver mines and built forts, roads, and housing for the army, church, and government. They performed agriculture and domestic labor in support of civilians, government contractors, and other elements of Spanish society. Even in regions where African slavery predominated, such as the sugar plantations in Portuguese Brazil and in the West Indies, Indian labor continued to be used. And in many Spanish colonies, where the plantations did not flourish, Indians provided the bulk of unfree labor through the colonial era. In other words, the growth of African slavery in the New World did not diminish the use of unfree Indian labor, particularly outside of the plantation system.

Whereas in South America and the islands of the West Indies, Europeans conducted the bulk of slaving raids against Indians, (except in Brazil, where bandeirantes of mixed blood were employed for slaving), much of the enslavement of Indians in North America above Mexico was done by Indians. North American Europeans did enslave Indians during wars, especially in New England (the Pequot War, King Philip’s War) and the southeast (the Tuscarora War, the Yamasee War, the Natchez War, just to name a few), but ordinarily Europeans, especially the English and French, purchased their Indian slaves from Indians. Colonists lured Indians to supply Indian slaves in exchange for trade goods and to obtain alliances with the Europeans and their Indian allies. Indians slaved against not only their enemies, but Indians they had never met. Many Indians recognized they had little choice but to become slavers. If they did not do the Europeans’ bidding they could easily become victimized themselves. It was not unusual for peoples victimized by slaving to become slavers, and for those who had been slavers to become the object of raids.

Colonists participated in Indian slave trading to obtain capital. It was as if capital could be created out of thin air: one merely had to capture an Indian or find an Indian to capture another. In South Carolina, and to a lesser extent in North Carolina, Virginia, and Louisiana, Indian slavery was a central means by which early colonists funded economic expansion. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, a frenzy of enslaving occurred in what is now the eastern United States. English and allied Indian raiders nearly depopulated Florida of its American Indian population. From 1670 to 1720 more Indians were shipped out of Charleston, South Carolina, than Africans were imported as slaves—and Charleston was a major port for bringing in Africans. The populous Choctaws in Mississippi were repeatedly battered by raiders, and many of their neighboring lower Mississippi Valley Indians also wound up spending their lives as slaves on West Indies plantations. Simultaneously, the New England colonies nearly eliminated the Native population from southern New England through warfare, slaving, and forced removal. The French in Canada and in Louisiana purchased many Indian slaves from their allies who swept through the Great Lakes region, the Missouri Country, and up into Minnesota. All the colonies engaged in slaving and in the purchase of Indian slaves. Only in the colonial region of New York and Pennsylvania was slaving limited, in large part because the neighboring Iroquois assimilated into their societies many of those they captured instead of selling them to the Europeans—but the Europeans of those colonies purchased Indian slaves from other regions.

Slaving against Indians did begin to decline in the east in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, largely a result of Indians’ refusal to participate in large-scale slaving raids, but the trade moved westward where Apaches, Sioux, and others continued to be victimized by Comanche and others. From Louisiana to New Mexico, large-scale enslavement of American Indians persisted well into the nineteenth century. Slave markets were held monthly in New Mexico, for instance, to facilitate the sale of Indians from the American West to northern Mexico. After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson sent federal troops into the West to put an end to Indian slavery, but it continued to proliferate in California.

The paradigm of “what happened” to American Indians under European colonialism must be revised. Instead of viewing victimization of Africans and Indians as two entirely separate processes, they should be compared and contrasted. This will shed more light on the consequences of colonialism in the Americas, and how racism became one of the dominant ideologies of the modern world. It is time to assess the impact of slave trading and slavery on American Indian peoples, slave and free.

Alan Gallay is the Warner R. Woodring Chair of Atlantic World and Early American History at The Ohio State University, where he is Director of The Center for Historical Research. He received the Bancroft Prize for The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (2003).

Portland was a robust maritime port in the mid-1800s. In addition to sugar cane, vessels delivered cotton from the South to feed the state’s textile industry.

Although many Mainers believed slavery was morally wrong, their economic interests were reliant upon industries that used slave labor.

“(Mainers were) caught in a dilemma between whether they want to support the union and the abolition of slavery versus their own incomes,” State Historian Earle Shettleworth Jr. said. “This is a very complex period in American history.”

During the 1800s, Maine – and Portland in particular – were an important cog in the so-called Trade Triangle.

Sugar cane from the South was shipped to Portland, where it was made into white granulated sugar and molasses on the city’s waterfront, which at one point imported three times as much sugar cane as Boston.

That molasses was then used to make rum, which in turn was used by human traffickers to acquire slaves, according to local historian Herb Adams.

“Maine was intimately connected to” the Trade Triangle, Adams said.

Such was the case with Nathaniel Gordon, a Portland native who has the distinction of being the only American to be tried, convicted and executed for trading slaves.

Gordon, who lived on Danforth Street, was captain of the slave ship Erie. He made three successful slave voyages before being caught by the U.S. steamer Mohican in 1860. Gordon, who had just traded vats of rum and whiskey for 900 slaves, was brought back to New York to stand trial. He was convicted in 1861.

Human trafficking was declared an act of piracy in 1820 that carried a punishment of death. However, it was unusual for slave traders to be prosecuted, let alone receive capital punishment for their crime.

The newly elected president, Abraham Lincoln, was eager to make an example out of Gordon, by hanging him in public.

According to an eyewitness account published in the Portland Daily Advertiser in 1862, Gordon, 28, took strychnine the night before his execution, but a doctor resuscitated him so he could be hanged on a gallows that, through a system of ropes and pulleys, lifts the prisoner 4 feet off the ground.

“Gordon was then led to the gallows, the rope adjusted, the black cap drawn over his face and he was launched off into eternity,” the author wrote.

“This is a great triumph,” the author continued. “It will strike terror which nothing else could into the hearts of traffickers of human flesh.”

Clifford, who never owned slaves or advocated for slavery, served as a Maine legislator in 1830 and speaker of the House in 1833, before becoming the state’s attorney general in 1834. He went on to serve two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives starting in 1838 and as the U.S. attorney general under President James K. Polk in 1846.

While on the Supreme Court, however, Clifford often voted with the majority of justices in favor of a strict interpretation of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and guaranteed former slaves with equal protections and rights – including the right to vote – as whites.

Clifford believed the amendments applied only to the federal government and didn’t extend to states, groups or individuals, Adams said.

His nomination to the Supreme Court was controversial in 1857. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate in 1858 by a thin margin of three votes – 26-23 – and died a justice in 1881.