With lawsuit against N.J., little-known Indian group is thrust into spotlight

on March 22, 2009 at 6:59 PM, updated March 23, 2009 at 10:44 AM

The story of the Sand Hill Indians and the $1 trillion lawsuit be gins on a wooded slope in Monmouth County.

Rising in Neptune Township, Sand Hill was settled 132 years ago by Lenape and Cherokee Indians who raised cows and chickens and helped build Victorian houses in nearby Asbury Park. Some of their descendants, who say they are more extended family than tribe, still gather for reunions near the ancestral hill.

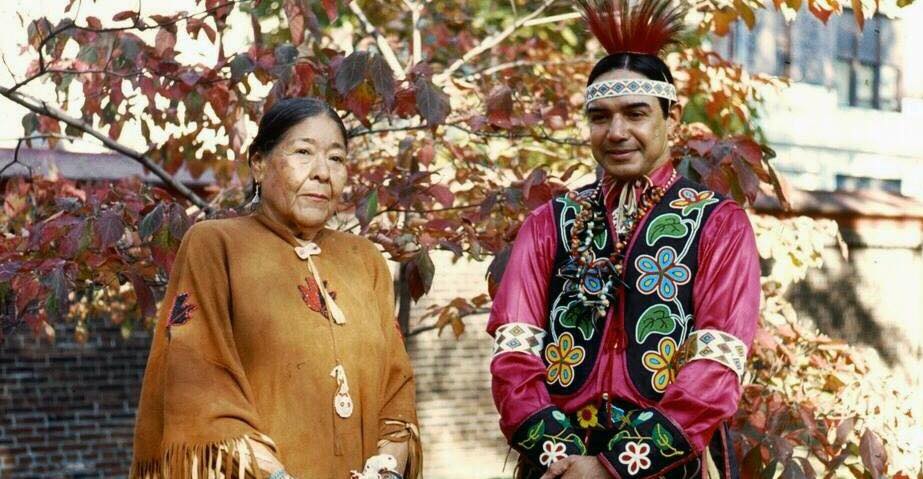

Claire Garland, a member of the Sand Hill Indians, holds a peace pipe that belonged to James “Long Bear” Revey, the tribe’s contemporary patriarch.

But during the last decade, a second group has surfaced in North Jersey, headquartered in Paterson. Its members also call themselves Sand Hill Indians, saying they are named after the same spot.

The trouble is, the Sand Hills of Neptune say the ones in Paterson aren’t Sand Hills at all. And therein lies the debate.

It began quietly as a disagreement about genealogy and bloodlines but gradually spiraled into a bitter feud. And now, with a federal lawsuit naming Gov. Jon Corzine and all 21 counties, that feud has thrust a spotlight on the Sand Hills — a little-known group that historians say may include some of the last few local descendants of New Jersey’s original inhabitants.

The suit was filed in U.S. District Court in Newark last month by two men — one from Australia, one from California — who say they are long-lost Sand Hills and are the Paterson group’s new leaders. Its demands include state recognition of the Sand Hills and $1 trillion in damages, paid in 1-ounce gold coins.

The move stunned the Sand Hills of Neptune. They accuse the two newcomers of hijacking their heritage to try to extract money from the government.

“They have stolen our name,” said Claire Garland, 64, a retired middle-school teacher and member of the Neptune contingent.

In an age of multimillion-dollar tribal casinos, competing genealogical claims among American Indians are fairly frequent, scholars say. But they can be tough to unravel. Tribes traditionally did not keep records. Many records they did have were lost during forced migrations. Bloodlines fade with time. Years later, it can be tough to prove who is related to whom.

“This kind of tangled web is common,” said Tom Kavanagh, a Seton Hall University professor of sociology and anthropology who studies American Indian cultures.

Roughly 50,000 people in New Jersey claimed some form of American Indian ancestry on the 2000 census. There are no federally recognized tribes based here.

But during the last three decades, the state Legislature has passed several resolutions acknowledging three groups: the Nanti coke-Lenni Lenape, whose tribal office is in Cumberland County; the Powhatan-Renape of Burlington County; and the Ramapough Lenape, headquartered in Mahwah.

Those resolutions, however, did not provide the groups with access to special services or tax breaks.

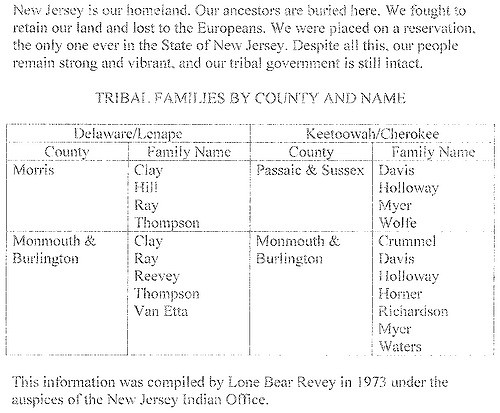

So who are the Sand Hills? The two sides agree on this much: The Sand Hills are descended from Lenape and Cherokee Indians who intermarried in New Jersey during the 19th century.

Five hundred years ago, New Jersey was home to the Lenape. Vestiges of their language echo in names like Hackensack, Manasquan, Watchung, Lackawana and Cheesequake.

The last large group of Lenape left the state in 1801. But a few clusters remained, including in Monmouth County, where they intermarried with Cherokee who had migrated from the Southeast, according to historians.

During the 1870s, a New York businessman built a summer resort amid the coastal woodlands near what is now Asbury Park. He hired local Lenape-Cherokee craftsmen and carpenters and in 1877 sold them 15 hillside acres, in what eventually became Neptune.

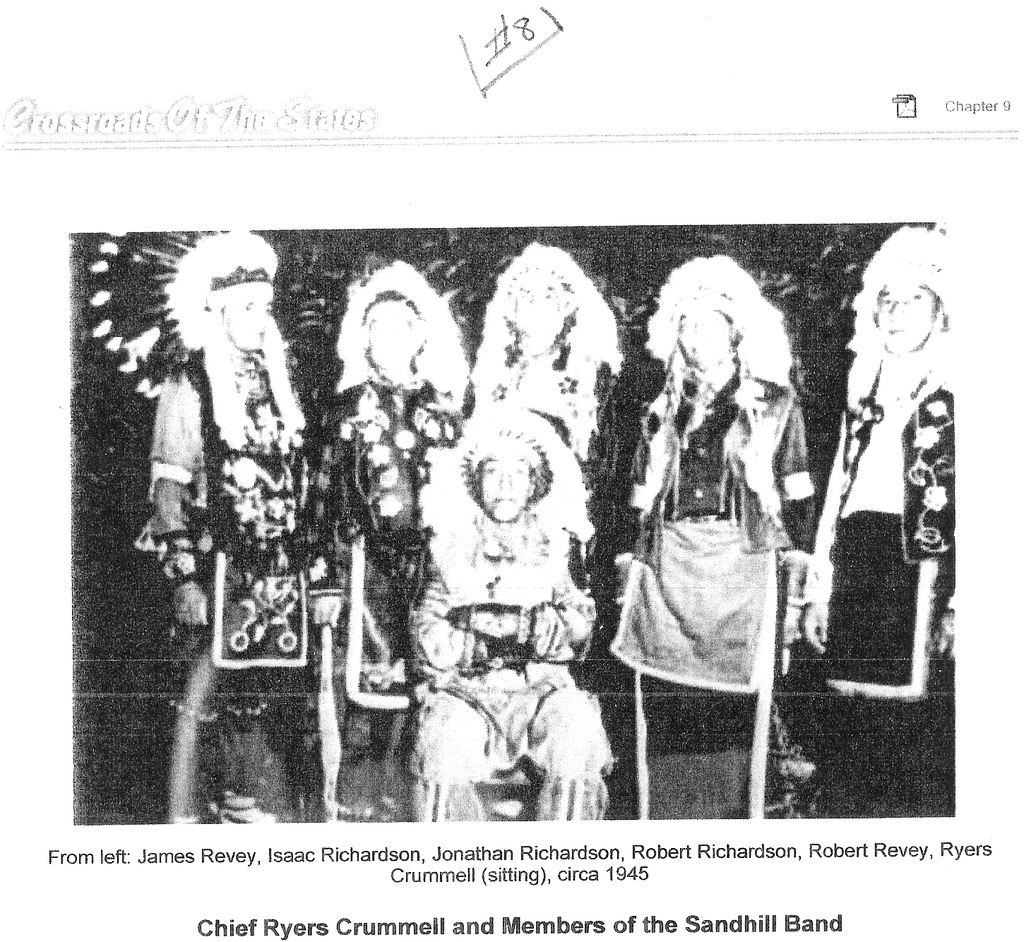

Locals called the spot Sand Hill. And the craftsmen and carpenters came to be called the Sand Hill Indians. They lived there for generations, working as builders, basket weavers and tanners. They had a chief and tribal council system and held ceremonial powwows.

But many of the traditions faded by the mid-20th century. The last powwow was in 1949, and the chief and council structure dissolved four years later, historians say.

“The old people died and nobody stepped up,” said Fortune Thomas, 62, who is Garland’s brother and owns an auto body shop in Tinton Falls.

Still, Thomas said the family gathered each Labor Day for reunions in Neptune, where members would grill corn, swap ancestral stories and pull crabs from the Shark River.

Things grew complicated after the 1998 death of James “Lone Bear” Revey.

Revey was the longtime head of the New Jersey Indian Office in Orange. Most say he was the Sand Hills’ contemporary patriarch.

But some — including the Paterson Sand Hills — contend Revey was more than an unofficial leader. They say he was chief.

Sam Beeler grew up in Paterson and has been active for years in local American Indian causes. As he recalls it, Revey lay dying at age 74 when he asked Beeler to assume leadership of the Sand Hills.

“He asked me to take over,” Beeler said.

And so Beeler became chief, he said.

That was news to the Sand Hills of Neptune.

“No one had ever heard of him in our family,” said Garland, who lives in Lincroft and has compiled a 17-page family tree stretching back to 1790 using property deeds, obituaries and other records.

At first Beeler and the Neptune Sand Hills were cordial, they said. But harmony was short-lived. Disagreements arose about who owned artifacts at the now-defunct Neptune Museum. Threatening letters were exchanged. Garland asked Beeler to stop calling himself chief.

Then two of Beeler’s relatives arrived: Carroll “Medicine Crow” Holloway and his son Ronald Holloway. They said they were Sand Hills, too.

The older Holloway is Beeler’s cousin and a Philadelphia native who has spent most of the last 30 years in Australia working as a fashion photographer. He moved to eastern Pennsylvania about two and a half years ago, according to his son.

In 2007, Carroll Holloway be came chief of the Paterson Sand Hills, whose official name is the Sand Hill Band of Lenape and Cherokee Indians. Ronald Holloway — who moved to New Jersey in November from a town 50 miles east of San Francisco — said he is now the group’s chief executive.

The lawsuit was filed last month. It surprised even some of the Paterson Sand Hills.

“That lawsuit was filed without the advice and consent of the tribal council,” said Yona Youngblood, a Paterson Sand Hill elder.

And why the $1 trillion in 1-ounce American Eagle gold coins?

“It’s a financial move that says that we are serious,” said Ronald Holloway, 45, who said he is a theologian and former police officer who holds a half-dozen securities licenses.

He is not a lawyer, but he plans to litigate the suit himself.

Garland and her relatives, meanwhile, say they don’t want the Sand Hill name used for any lawsuit against the state.

“They are trying to use our legitimacy and heritage to make themselves look credible,” said Garland, who lives in Lincroft.

Part of the two groups’ disagreement is about how to define who is a Sand Hill.

By Garland’s measure, the only true Sand Hills are direct descendants of the single Lenape-Cherokee family that bought the 15 hillside acres in 1877. But Beeler and the Holloways contend there are 14 families who make up the group and only one of them actually lived on Sand Hill.

They also say James “Lone Bear” Revey was their cousin.

Not so, said Revey’s niece, Carol Clarke.

“As far as I know they are not my relatives,” said Clarke, who lives in Hempstead, N.Y.

The two sides also differ on the matter of chiefs.

Beeler and the Holloways tell of an unbroken string of chiefs going back hundreds of years, ending with Revey, Beeler and Holloway.

Most historians say that’s not true. And Revey himself wrote in a history of the Sand Hills that the group’s chief and council system dissolved in 1953.

These days, the Sand Hills of Neptune and the Sand Hills of Paterson are no longer speaking. Their dispute and especially the lawsuit — has jolted the state’s American Indian community, said the Rev. John Norwood, a member of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape.

“It casts a cloud,” Norwood said. “And it airs a dispute that should be handled inter-tribally.”

Ronald Holloway, however, predicted the suit would once and for all settle the question of who is a Sand Hill and who is not. Claire Garland hopes he is right.

“I don’t care what they do in North Jersey,” she said. “It has nothing to do with us. But using our name to sue the governor is a whole other story.

Mitsu Yasukawa/The Star-Ledger

Mitsu Yasukawa/The Star-Ledger