Hunting North AmericanIndians in Barbados

Hunting North AmericanIndians in BarbadosPatricia Penn Hilden

University of California, Berkeley

May, 2002

This is a story. It is an abbreviated story of a quest, one that is far from finished. It begins with my first meeting with the great Caribbean poet, Kamau Brathwaite, on a rainy night in Canterbury, England, where Brathwaite was giving the first of three T.S. Eliot Lectures. That night, I heard him sing and drum and chant the echoes of West Africa, sounds he had found in Barbados, sounds he had heard as a child but which he hadn’t then recognized because of the opposing cacophony of “Lil’ England” noise then prevalent in Bajan identity formation. As I listened, I found myself thinking two things: first, that the indigenous sounds of North America were similarly muted, and even silenced, in our own version of “Lil’ Englandism”, and second, that something in what he was doing recalled an Indian amongst that African sound. At that time, I only wondered, though I began to talk to Kamau about this idea as the years passed and our friendship grew.

Then I visited Kamau Brathwaite in Barbados and he took me to look for Indians, in this case, the Arawaks, who had “disappeared” almost immediately after the first contact with Europeans, their diseases and their guns. We sought a site around a point at Pico. Brathwaite has written of this place, in Barabajan Poems.

whole wild Maroon coast from RiverBay right

round to Pico & the miracle of Cove the ancien

(T) Amerindian religious settlement, through Ca-

ttlewash to Martin’s Bay and congoRock & Con-

setts in the distance…”1

We didn’t find Pico that day, though I have been there since. It remains a sacred place, despite the depredations of artifact-hungry archaeologists, who have lifted as much as possible of the indigenous material history of the island and placed it inside the post-independence Barbados Museum, where it lies in a special room designated “prehistory”, producing a “heritage” for contemporary Barbadians in a manner familiar in North America.

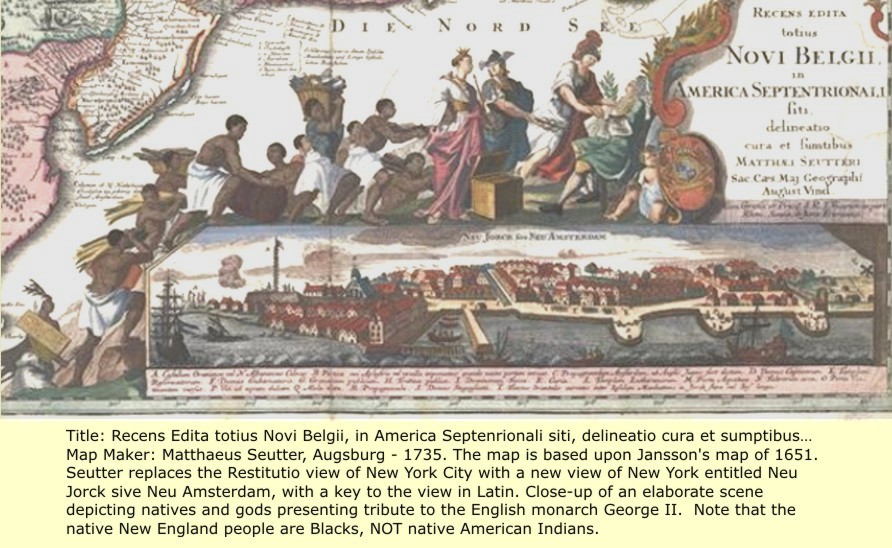

But despite this assignment of Arawaks to a “pre-European, pre-African past”, I continued to find Indians in Barbados. I kept seeing “Indian” place names, hearing “Indian” sounds. I knew, of course, that Indian slaves had come from South America and from the Mexican coast. But I knew also that many thousands of North America’s indigenous peoples had been captured and sold into slavery. In fact, near the end of the 17th century, the Wampanoag leader, Metacomet, known to the English as King Philip, had warned New England’s tribal people: “these people from the unknown world will cut down our groves, spoil our hunting and planting grounds, and drive us and our children from the graves of our parents and our council fires, and enslave our women and children.”2 I knew that tribal people had worked across the colonies, enslaved in households and workshops, on farms and in fisheries. I knew, too, that Indian slaves worked side by side with African slaves, constituting 1/3 of the slaves in early 18th century South Carolina, for example. Moreover, a handful of historians, Almon Lauber in 1913, followed by Caroline Foreman (1943) and Jack Forbes (1993), had argued that the trade in North American Indian slaves did not limit itself to the North American colonies or even to the trade between America and Europe. So I began to wonder if some North American Indians had not formed part of the slave population in Barbados and thus possibly provided the sources for the place names – “Indian Pond,” “Indian Ground,” “Indian Corner” – that dot the Barbados landscape. My quest had begun.

I started in the National Archives of Barbados, looking first, rather randomly, through late 17th century records. I quickly discovered that all the myriad – and hopeless – efforts to regulate and control slave rebellion referred consistently to “African and other slaves”. But I knew that Indian slaves had also been brought from Guyana and from Venezuela, so these could well have been the “others” referred to. Then I came across the following act, dated June 1676:

“Act to Prohibit the Bringing of Indian Slaves to this Island”

“This Act is passed to prevent the bringing of Indian slaves and as well to send away and transport those already brought to this island from New England and the adjacent colonies, being thought a people of too subtle, bloody and dangerous inclination to be and remain here…..”

So there I had it: clear evidence that North America Indian people had indeed worked in Barbados’s sugar plantation world. I then took up Richard Hall’s Acts Passed in the Island of Barbados from 1643-1762.3 Here, too, were the tantalizing suggestions hidden in the language of more efforts to halt or prevent rebellion. I have time to read only a few:

27 October 1692: “An Act for the encouragement of all Negroes and other slaves that shall discover any conspiracy…”

———————-: “An Act for prohibiting sale of rum or other strong liquor to any Negro or other Slave…”

———————-: “An Act for the encouragement of such Negroes and other slaves that shall behave themselves courageously against the enemy in time of invasions (manumitted if two white men proved that they killed an enemy)…”

And even more specific wording:

6 January 1708: “An Act to prevent the vessels that trade here, to and from Martinico or elsewhere, from carrying off any Negro, Indian, or Mulattoe slaves….”

11 November 1731: “Act for amending an Act…entitled ‘Act for the Governing of Negroes and for providing a proper maintenance and support for such Negroes, Indians, or Mulattoes as hereafter shall be manumitted or set free….”

Then a diversion. I encountered the only person who had then written about Indian slavery in Barbados, Jerome Handler. In 1968 he had written about the 1676 law but, knowing nothing of the history of North American Indian slavery, had reached different conclusions. Handler argued that North American natives formed only a minuscule, and therefore insignificant, number of Barbadian slaves. All the geographical references to “Indians”, he insisted, referred only to Caribs or Arawaks, or to Indians brought from South America or the other Caribbean islands. “By the end of the first few decades of the eighteenth century,” Handler wrote, there are few traces of [North American Indians] existing as a distinctive sub-cultural group.”4

But “traces,” I knew, are more significant than Handler allowed. Stubbornly, I went on looking.

There were words, and here are a few:

At the beginning of the 18th century, in a South Carolina peopled by Indians, Africans, and Europeans, where Charleston formed the heart of the bustling North American-Caribbean slave trade, “mustee” meant people born of all three. In 1770, another word. In Scotland a Society of Gentlemen offered this definition of “mulatto” in their Encyclopedia Britannica: or a Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: “Mulatto: a name given in the Indies to those who are begotten by a Negro man on an Indian woman, or an Indian man on a Negro woman.”5

At the same time, North American colonial history was replete with references to Indians captured and sold into the slave trade, references often riddled with stereotypes born, as we shall see below, from the first moments of African Indian slavery. James Axtell, a noted scholar of the colonial era, offered a typical version of events: “The English incited ‘civil’ war between the tribes….[then] rewarded one side for producing Indian slaves who were then sold to the West Indies, often for more biddable black slaves.”6Axtell’s absurd assertion, that “black slaves” were more desirable because more tractable, is repeated across United States history. Here is Yasuhide Kawashima, writing of Pequot warriors captured after escaping the Puritans’ genocidal attempt to exterminate their people in the 1630s.7 After capture, they were “sold to the West Indies in exchange for more docile Blacks who became the first Negro slaves in New England.” There are others like these two, purveying the same general idea, though with varying degrees of bigotry.

How did this stereotype of willing Black slaves and rebellious Indian slaves arise? Mason Wade offers a clue: “The French…at Biloxi and New Orleans attempted to use Indian slaves to work the tobacco plantations but these ran away and it was decided to import Blacks from the French West Indies.”8

Of course. Indians could run away – to their own tribes, to other Indians, to escaped Black slaves in the many maroon communities that soon grew up wherever there was African slavery. So long as they were home, Indians knew where they were – much better than any European, as the records of Indian rescues of witless Europeans attest. Rather than trading boatloads of rebellious Indians for cargoes of “biddable” Africans, it is surely more likely that the English – in New England, Virginia, Barbados, and elsewhere – rounded up and exported any leaders or fomenters of rebellions, whether African or Indian. Removed from whatever place and community they knew, they were perhaps more easily subdued, more easily reduced to a state of hopeless exhaustion characteristic of any dislocated, enslaved peoples. (But it should be reiterated here that the laws of the Barbados Assembly testify eloquently to the constancy with which enslaved peoples continued to rebel, to run.)

Still, some more recent histories take a different view. Jill Lepore’s In the Name of War, which narrates the Europeans’ version of King Philip’s War, takes note of the exchange of African and Indian slaves without characterizing either as “tractable” or “biddable.” Indeed, she links Nathaniel Saltonstall’s Continuation of the State of New-England, together with an Account of the Intended Rebellion of the Negroes in the Barbados, published in London in 1676, to the simultaneous revolt of New England Indians. “Terrified English colonists in Barbadoes believed that the Africans had ‘intended to murther all the white people there,’ just as panicked English colonists in New England feared that the Indians had ‘risen almost round the countrey.'” She concludes, “the parallels between the two uprisings were uncanny and profoundly disquieting.” Moreover, Governor Berkeley of Virginia complained in that same year that “the New England Indian infection had spread.” And Barbados’s panicky governor, Jonathan Atkins, had sent a similar warning to London shortly before: “the ships from New England still bring advice of burning, killing, and destroying daily done by the Indians and the infection extends as far as Maryland and Virginia.”9

So there is some hope for the overturning of this canard. Still, this stereotype, once spread through the colonies, continued for a long time to “justify” the importation of vast numbers of Africans to “replace” the “disappearing” Indians who were, of course, being sold for profit to the Caribbean. However scarce, Indians continued to be captured and sold to Barbados. After the 1670 founding of Charlestown by Sir John Colleton and his fellow Barbadians, dozens more landless Barbadians flocked to the area where they quickly replicated Barbados economic and social practices. Anthony MacFarlane tells us, “there was…an ominous sign that [Carolina] would eventually follow [Barbados’s] path, in that the settlers took Indians as slaves, both for their own use and for export to the West Indies.”10 As commodities on the slave market, Indians were quite valuable. In neighboring Virginia in that era, “a child was worth more than her weight in deerskins; a single adult slave was equal in value to the leather produced in 2 years of hunting…By the latter half of the 17th century, if not before,” Joel Martin reports, “slavery was big business in Virginia, an important part of the English trading regime.”11

Marking the historical moments when the British sold captive Indians into the Caribbean slave trade is possible. Every single rebellion against the invaders, beginning with the first organized resistence to the Virginians at the beginning of the 17th century and continuing through the Pequot genocide (1630s), and Metacom’s Rebellion (1675-76), produced Indian slaves for the Caribbean trade. The slave trade was extensive. There is room here for only a few examples. The Carolinians waged a long struggle with Spain in Florida, the fruits of which were often captive Indians. Between 1702 and 1707, thousands of missionized Indians – already trained into docility and servitude – were sold into the Caribbean. The next year, Englishmen in the Carolinas seized between 10,000 and 12,000 more Christianized Indians and quickly dispatched them to slave islands in the West Indies. The Tuscaroras and Yamassees were so afflicted by these English colonial practices that both nations went to war to try to stop it. Both paid a heavy price, though the Tuscaroras survived. When they inevitably lost their 1711 war, the entire surviving population managed to flee north where they found refuge with the five nations of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, ultimately surviving as the sixth nation of a confederation that continues today. The Yamassees, some of whom were part of the missionized Indians captured earlier, waged a long war against this slave trade, a war that lasted from 1715-28. They paid the ultimate price, their defeat signaling the virtual disappearance of the Yamassee nation though some survivors fled to other nations or to one of the hundreds of maroon communities across southeastern North America. A few years later, the defeat of the great pan-Indian rebellion of 1736-66, led by the famous war chief Pontiac, sent still more Indians on their way to Caribbean cane houses and cane fields. And from all the other invaded regions of North America came more rebellions, more slaves.

All the years between these markers, all over North America, slave raids and violent conflict produced humans for sale. The “Plantation Records” of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society carry these few documentary fragments. In 1630, John Winthrop sold an Indian to John Mainford of Barbadoes. Two decades later, Richard Ligon visited the island and recorded his “true and exact history”, published upon his return to London in 1657.12 Ligon recorded many encounters with “Indian” slaves, many working in the houses of his hosts. One woman taught him how to make corn pone by “scaring it very fine (and it will fall out as fine as the finest wheat-flower in England….).”13 Indian men slaves made “perino”, a drink “for their own drinking…made of Cassavy root, which I told you is a strong poyson; and this they cause their old wives, who have a small remainder of teeth, to chaw and spit out into water….”14 Ligon liked the Indians he met. He remarked, “As for the Indians, we have but few, and those fetcht from other Countries;…which we make slaves; the women who are better vers’d in ordering the Cassavie and making bread then (sic) the Negroes, we imploy for that purpose, as also for making Mobbie: the men we use for footmen and killing of fish, which they are good at; with their own bowes and arrows they will go out; and in a dayes time, kill as much fish as will serve a family of a dozen persons two or three dayes….They are very active men, and apt to learn any thing sooner than the Negroes….they are much craftier and sutiler then the Negroes; and in their nature falser; but in their bodies more active…”15

Of course generations of African diaspora scholars have demolished this kind of reading of the behavior of African slaves – wiser than the Indians in not leaping to do the bidding of owners and far “subtler” in keeping their attitudes to themselves. But that Ligon so admired these Indians suggests the extent to which the Barbadian plantocracy shared these views and was anxious to accumulate more such people.

Shortly after Ligon’s return home, the Barbados Museum records tell us, a large number of Narragansetts from Connecticut were sold to Barbados. In 1668, at least one Indian slave was sent from Boston to the island while in 1700, a “big sale” of Indians from North America to the West Indies occurred. A year later, in 1701, Acolapissa Indian captives were sold by Virginians into the Caribbean.

The early 18th century saw no end to this trade though the bulk of the market may have begun to shift to the French speaking Caribbean as the British continued their conquest westward and as the French continued to use the slave trade’s profits to support their war efforts.16 In 1729 the Louisiana French, together with their Choctaw allies, put an end to constant Natchez Indian revolts, capturing the Natchez war leader, Great Sun, plus some 480 others, and selling them all to the West Indies. The capture and sale of Natchez people to the islands continued until, one historian notes bleakly, by 1742 “the Natchez tribe had virtually disappeared.”17

Small little markers – ephemeral traces – but signs nonetheless of a vast dislocation, a terrible colonial “trail of tears” as later forced removals came to be known. Indians slaves were useful; Indians slaves were profitable; Indian slaves left behind land for the Europeans to steal.

The quest continues, and there isn’t time to narrate the further fragments I have found. But it is clear to me now that Indian voices, muted, mixed in the “Negroe, Indian, and Mulattoe” slave worlds of the 17th and 18th centuries, form an as yet little heard chorus, mixed into the complicated sounds of Barbados that Kamau Brathwaite has given that nation and the world. Even as I listened to Kamau sing us the drumming sounds of Mile and a Quarter that drizzly night in Canterbury, I really did hear, too, the softer sounds audible nearby at “Indian Groun(d)” (now a Seventh Day Adventist Church), these the sounds of the houmfort, the tonelle, the music of his Great Uncle Bob’ob the Ogoun (and the sounds of prejudice: “white man better than red man better than black man”18 ). It was not a fantasy. Hearing Brathwaite, I was hearing our Indian sounds, too, the drumming, the sounds of moccasined feet dancing the earth.

The extent of the trade in North American Indians that I and others are beginning to document becomes clearer with each foray into the archives. And increasingly the question becomes why the silence? I think there are two basic reasons. First, the overculture’s silence is easily explained by the fact that its historians never want to come to terms with a bloody and terrible past. The acknowledgment of African slavery by overcultural U.S. historians took decades of struggle by African American scholars and activists. That the indigenous genocide hidden behind all United States history has yet to be recognized is, like the issue of Indian slavery, due to the powerlessness of indigenous peoples and – it must be said – to their own reluctance. The trade in Indian slaves was profitable both to whites and to Indians, and in many cases, the capture and sale would never have reached the extent it did without the active participation of indigenous people themselves. In a time when indigenous peoples are struggling to re-write their own histories, tell their own stories, interpret their own literatures in their own indigenous ways, research not surprisingly focuses less on the painful histories of collaboration and inter-tribal warfare and more on resistance and struggle. But the whole story, the entire past, matters – to all of us. And so this work must be done. Beyond the enriching of Native America’s own history, as well as that of the overculture, there are other implications buried within this quest. Here, too, scholars of the African diaspora have given us a crucial lead, and we must follow it. A few examples only. As Judith Carney has painstakingly recorded the African roots of southern rice production, so Indian scholars must add the Indian roots of that same agriculture. As Michael Gomez has shown us with precision the African origins of southern slaves, so we must try to track our own peoples as they disappeared into the vast maw of the West Indian slave markets. As Kamau Brathwaite has recorded the African cultural roots of Bajan identity, so we must add the North American Indian contribution – to the Bajan world, as well as to the world across the Caribbean. It is time, as I realize again every time I am swamped by invitations to come to Jamaica, to the Dominican Republic, to Haiti, to Martinique and Guadaloupe, to Cuba, and back to Barbados whenever I speak of this work. Women I meet tell me that their old grannies have always told the grandchildren that they were Indian as well as African. They want me to come tell these ladies that this is so and why before their grannies die. Others – Caribbean people now living in the United States – recount similar family stories, tales that always before seemed preposterous to many of their hearers, or tales that many argued linked people of African descent only to the Arawaks or Caribs but never, ever to North American Indians.

But perhaps it is more than this. Perhaps for us indigenous scholars, it is just now, at last, time. In the words of Haitian scholar Michel-Rolph Trouillot:

“At some stage, for reasons that are themselves historical, most often spurred by controversy, collectivities experience the need to impose a test of credibility on certain events and narratives because it matters to them whether these events are true or false, whether these stories are fact or fiction.”