#Gaythelos#Hiber &#Eqyptian_Scots: “… an Egyptian exodus that did indeed conclude in Scotland….Ellis establishes that Scota was really Ankhesenamun, daughter of Akhenaton and Nefertiti, and wife of Tutankhamen. He also finds that far from being a Greek king, Gaythelos was a pharaoh himself – Aye. Little is known of Aye, although Ellis speculates that he was the father of Tutankhamen and married Ankhesenamun after his son’s death. Aye ruled only briefly before religious struggle brought him into conflict with the Egyptian people and he and his court were forced into exile….Having established the origins of Scota/Ankhesenamun and Gaythelos/Aye, Ellis tracks them as they flee. He contends that the couple took enough ships to bring 1,000 of their followers and plentiful supplies out of Egypt and across the Mediterranean. He finds that they landed first in Spain, where they lived for several generations (their son Hiber giving his name there to Iberia). Four generations after they first settled, the descendents of Scota made their way to Ireland….”

#Gaythelos#Hiber &#Eqyptian_Scots: “… an Egyptian exodus that did indeed conclude in Scotland….Ellis establishes that Scota was really Ankhesenamun, daughter of Akhenaton and Nefertiti, and wife of Tutankhamen. He also finds that far from being a Greek king, Gaythelos was a pharaoh himself – Aye. Little is known of Aye, although Ellis speculates that he was the father of Tutankhamen and married Ankhesenamun after his son’s death. Aye ruled only briefly before religious struggle brought him into conflict with the Egyptian people and he and his court were forced into exile….Having established the origins of Scota/Ankhesenamun and Gaythelos/Aye, Ellis tracks them as they flee. He contends that the couple took enough ships to bring 1,000 of their followers and plentiful supplies out of Egypt and across the Mediterranean. He finds that they landed first in Spain, where they lived for several generations (their son Hiber giving his name there to Iberia). Four generations after they first settled, the descendents of Scota made their way to Ireland….”

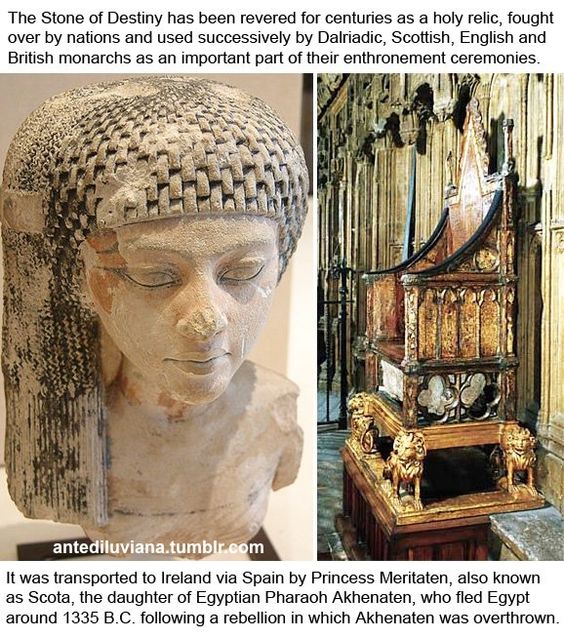

The pharaoh’s daughter who was the mother of all Scots

WALTER Bower wrote his compendium of Scottish history, Scotichronicon, in the 1440s.

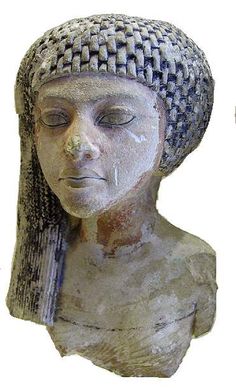

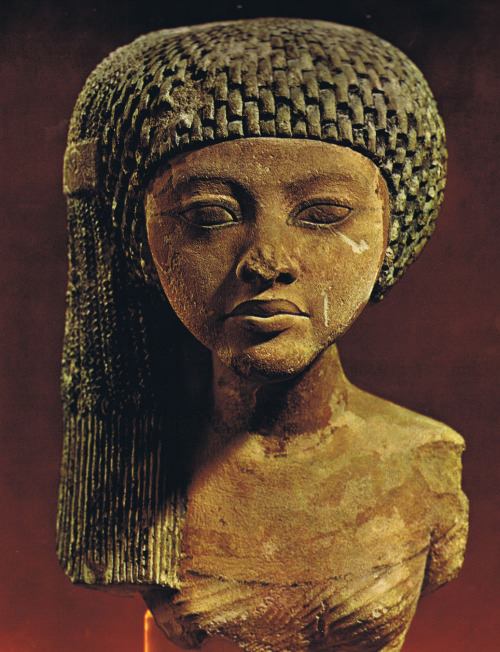

This sweeping Latin text aimed to set down the history of the Scottish people from the earliest times – and by so doing to show what race of people we were. He referenced his chronicle from ancient texts and oral history. What he recorded was astounding. According to Bower, the Scottish people were not an amalgam of Picts, Scots and other European peoples, but were in fact Egyptians, who could trace their ancestry directly back to a pharaoh’s daughter and her husband, a Greek king.The queen’s name was Scota – from where comes the name Scotland. The Greek king was Gaythelos – hence Gaelic, and their son was known as Hiber – which gives us Hibernia. Nor was Bower the first to propose such exalted lineage for the Scots. The story goes back further and was even included in The Declaration of Arbroath. This seminal document – written in 1320 by the Barons and noblemen of Scotland – was a letter imploring the Pope to intervene on their behalf during the Wars of Independence. The text refers to “the ancients” who “journeyed from Greater Scythia … and the Pillars of Hercules … to their home in the west where they still live today”. According to tradition, this royal family was expelled from Egypt during a time of great uprising. They sailed west, settling initially in Spain before travelling to Ireland and then on to the west coast of Scotland. This same race of people eventually battled and triumphed over the Picts to become the Scots – the people who united this country. Few historians have taken the story to be anything more than a verbose bit of Middle Ages origin story-spinning, created by a nation who needed to prove that they were of ancient stock. “Most political entities [in medieval times] try and trace the origin of their race back into biblical times,” says Steve Boardman, lecturer in Scottish history at Edinburgh University. “It was a way of asserting the natural existence of the kingdom of the Scots.” But now a new book, Scota, Egyptian Queen of the Scots, by Ralph Ellis, claims to prove that this origin myth was no made-up story but the actual recording of an Egyptian exodus that did indeed conclude in Scotland. In tracing the sources that could have influenced the Declaration and Bower’s Scotichronicon, he finds that the main British reference was likely to be the eighth-century historian Nennius. But it is in tracing Nennius’s sources that Ellis thinks he’s found the answer. He believes that that the originator of the Scota Gaythelos story was an ancient text, The History of Egypt, written in 300BC by an Egypto-Greek historian called Manetho.Ellis writes: “The possibility that Manetho was the original author of the Scota and Gaythelos story is interesting, because it gives the whole story much greater credence.” Having traced the original source – which was, if not contemporaneous, at least reasonably informed – Ellis believes that we can begin to put flesh on the bones of this story. Using Manetho’s text, Ellis establishes that Scota was really Ankhesenamun, daughter of Akhenaton and Nefertiti, and wife of Tutankhamen. He also finds that far from being a Greek king, Gaythelos was a pharaoh himself – Aye. Little is known of Aye, although Ellis speculates that he was the father of Tutankhamen and married Ankhesenamun after his son’s death. Aye ruled only briefly before religious struggle brought him into conflict with the Egyptian people and he and his court were forced into exile. Having established the origins of Scota/Ankhesenamun and Gaythelos/Aye, Ellis tracks them as they flee. He contends that the couple took enough ships to bring 1,000 of their followers and plentiful supplies out of Egypt and across the Mediterranean. He finds that they landed first in Spain, where they lived for several generations (their son Hiber giving his name there to Iberia). Four generations after they first settled, the descendents of Scota made their way to Ireland. Here Ellis refers to Irish stories, but supplements the myth with facts. He points to the number of gold torcs – necklaces worn by pharaohs – that have been found in the country. He shows us tombs that were surely built with Egyptian knowledge. He even finds us a mummified head that demonstrates that Scota’s people took their method of embalming their dead with them from Egypt halfway across the world.From Ireland it was a short hop across the water as later Iberian “Egyptians” seeking a new homeland in Ireland were told to populate Scotland. This colony became so successful that eventually many of the original Irish “Scots” then moved across too. It all seems exceptionally compelling. Who’s to say that just because it’s unlikely it isn’t actually possible? Well, most historians for one. Boardman says of Ellis’s research that to “search for historical figures is just madness. It’s never going to work”. He concludes, that much as medieval Scots – and clearly present-day ones too – would like to believe in these ancient roots there isn’t much chance that it is true. “Because of our training we never like to say a definitive no,” says Boardman. “But as far as I could, I would say that it is all nonsense.” If you enjoyed reading this, you may want to read: The Grail, Jesus’s children and Stone Age lasers: Scotland’s madder myths

QUEEN SCOTIA – FROM EGYPT TO IRELAND

Scota appears in the Irish chronicle Book of Leinster (containing a redaction of the Lebor Gabála Érenn). According to Irish Folklore and Mythology, the battle of Sliabh Mish was fought in this glen above the town of Tralee, where the Celtic Milesians defeated the Tuatha Dé Danann but Scotia, the Queen of the Milesians died in battle while pregnant as she attempted to jump a bank on horseback. The area is now known as Scotia’s Glen and her grave is reputed to be under a huge ancient stone inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs. She was said to be a Pharaoh’s daughter and had come to Ireland to avenge the death of her husband, the King of the Milesians who had been wounded in a previous ambush in south Kerry. It is also said that Scotland was named after Queen Scotia.

The book ‘Kingdom of the Ark’ by Lorraine Evans reveals numerous archaeological connections between Egypt and Ireland. Evans argues the remains of an ancient boat in Yorkshire, a type found in the Mediterranean was over 3000 years old from around 1400 to 1350 BC. She tells the story of Scota, the Egyptian princess and daughter of a pharaoh who fled from Egypt with her husband Gaythelos with a large following of people and settling in Scotland. From here they were forced to leave and landed in Ireland, where they formed the Scotti, and their kings became the high kings of Ireland. In later centuries, they returned to Scotland, defeating the Picts, and giving Scotland its name.

In A Folk Register, A History of Ireland in Verse, contemporary historian Patrick J. Twohig moves the legend to about 400 BC but still writes:

The day of poets and iron men

Had dawned, and with a clang…

Long had they coursed, the sons of Mil

From Scythia’s Black Sea shore,

Goidels (Gaels) who journeyed to fulfill

Their destiny of yore…

What emerges from all this is the faint possibility that an Egyptian princess met a Scythian warrior, and became his bride, centuries after the date given in the ancient table. And, since Egypt did fall to invaders in the mid-fourth century BC, it is possible some Egyptians did flee to Spain and – finally – got to Ireland at about that time.

Scotia’s links with reality are, admittedly, quite tenuous. Yet down there in the glen, the legend somehow complements the history and the great stone seems stronger than the ‘facts’ as the Finglas trips by bubbling – almost winking – in the sun.

Photo: Signpost on by-road, Queen Scotia’s Grave Walk, Scotia’s Glen, Tralee, Co Kerry