All my Slaves, whether Negroes, Indians, Mustees, Or Molattoes.’1

Towards a Thick Description of `Slave Religion’

by Patrick Neal Minges © 1999

The time was in the late 1760’s and the place was Charleston, S.C. A young musician was on his way to a performance with his french horn tucked under his arm. As he passed by a large meetinghouse, he heard much commotion on account of a “crazy man was halloing there.” He might have ignored the event but his companion dared him to “blow the french horn among them” and disrupt the meeting. Thinking they might have some fun, John Marrant and his companion entered the meeting hall with the intent of mischief. As he lifted his horn to his lips, the crazy man — evangelist George Whitefield — cast an eye upon him, pointed his finger at John Marrant and uttered these words: “Prepare to Meet Thy God, O Israel!” Marrant was struck dead for some thirty minutes and when he was awakened, Reverend Whitefield declared “Jesus Christ has got thee at last.” After several days of ministrations by Reverend Whitefield, the Lord set John Marrant’s soul at liberty and he dedicated his life to the propagation of the gospel.2

Marrant first witnessed to members of his family and when they rejected his newfound evangelical spirit, he fled to the wilderness where he sought solace among the beasts of the woods. Marrant was not afraid for God hade made the beasts “friendly to me.” When Marrant happened upon a Cherokee deer hunter, they spent ten weeks together killing deer by day and preparing brush arbors by night to provide sanctuary for themselves in the wilderness. Becoming fast friends by the end of the hunting season, the Cherokee deer hunter and the African American missionary returned to the hunter’s village where they would continue their cultural exchange. However, when he attempted to pass the outer guard at the Cherokee village, the Cherokees were less than excited with Marrant and he was detained and placed in prison.3 It was not that Marrant was a black man that troubled the Cherokee, the peoples of the Southeastern United States had relations with Africans that stretched back perhaps as far as a thousand years.4 It was just that ever since black people had started showing up with their friends, the white people, that things had started going particularly bad for the Indians of the Southeastern United States.5

It seems that as soon as Europeans showed up on the coasts of the United States, they started reading from a formal document called the Requierimento that declared themselves to be Christians and by nature superior to the uncivilized heathens that they encountered.6 The indigenous people were then informed by the Requierimento that if they accepted Christianity they would become the Christian’s slaves in exchange for the gift of salvation; if they did not accept the gospel of Christianity, they would still become slaves but that their plight would be much worse.7 Everywhere that explorers such as Ponce De Leon, Vazquez De Ayllon, and Hernando De Soto went on their “explorations” throughout the American Southeast, they carried with them bloodhounds, chains, and iron collars for the acquisition and exportation of Indian slaves.8 A Cherokee from Oklahoma remembered his father’s tale of the Spanish slave trade, “At an early state the Spanish engaged in the slave trade on this continent and in so doing kidnapped hundreds of thousands of the Indians from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts to work their mines in the West Indies.”9

No sooner had they set foot on shore near Charleston S.C. than the English set about upon establishing the “peculiar institution” of Native American slavery. Seeking the gold that had changed the face of the Spanish Empire but finding none, the English settlers of the Carolinas quickly seized upon the most abundant and available resource they could attain The indigenous peoples of the Southeastern United States became, themselves, a commodity on the open market.10 Applying the same rhetoric that they had used in their genocidal campaign against the “heathens” and “barbarians” of Scotland and Ireland,11 the Carolinians cited Indian “savagery” and “depredations” as justification for “Indian wars” to dispossess and enslave the Yamasee, the Tuscarora, the Westo and eventually the Cherokee and the Creek.12

| “The Indian slave trade in the Carolinas, with these southern ports as their centers, rapidly took on all of the characteristics of the African slave trade. “ | |

Charleston and Savannah quickly became the centers of this North American commercial slavery enterprise. In the latter half of seventeenth century, Native American nations throughout the South were played against each other in an orgy of slave dealing that decimated entire peoples.13 The Indian slave trade in the Carolinas, with these southern ports as their centers, rapidly took on all of the characteristics of the African slave trade. The Carolinians formed alliances with coastal native groups, armed them, and encouraged them to make war on weaker tribes deeper in the Carolina interior.14 By the late years of the seventeenth century, caravans of Indian slaves were making their way from the Carolina backcountry to forts on the coast just as caravans of African slaves were doing on the African continent. Once in Charleston, the captives were loaded on ships for the “middle passage” to the West Indies or other colonies such as New Amsterdam or New England.15Many of the Indian slaves were kept at home and worked on the plantations of South Carolina; by 1708, the number of Indian slaves in the Carolinas was nearly half that of African slaves. 16

Soon the Cherokee would become a major victim in the slave trade; as early as 1681, a permit was issued for the export of two “Seraquii slaves” from Charleston.17 By 1693, the Cherokee had become objects of the slave trade to the extent that a tribal delegation was sent to the Royal Governor of South Carolina to protect the Cherokee from Congaree, Catawba, and Savannah slave-catchers.18 In 1705, the Cherokee accused the colonial governor of granting “commissions” to slave-catchers to “set upon, assault, kill, destroy, and take captive” Cherokee citizens to be “sold into slavery for his and their profit.” 19 The Cherokee slave trade was so serious that it had, by the early half of the eighteenth century, eclipsed the trade for furs and skins, and had become the primary source of commerce between the English and the people of South Carolina.20

In 1619, a Dutch man-of-war arrived on the Virginia coast carrying African slaves for the American market; over a period of some one hundred years between 1650 and 1750, the face American slavery began to change from the “tawny” Indian to the “blackamoor” African.21 The unsuitability of the Native American for the labor-intensive agricultural practices, their susceptibility to European diseases, the proximity of avenues of escape for Native Americans, and the lucrative nature of the African slave trade led to a transition to an African-based institution of slavery.22 In spite of a later tendency in the Southern United States to differentiate the African slave from the Indian, African slavery was in actuality imposed on top of a pre-existing system of Indian slavery.23 In North America, the two never diverged as distinctive institutions.24

During this period of transition, Africans and Native Americans shared the common experience of enslavement.25 In addition to working together in the fields, they lived together in communal living quarters, began to produce collective recipes for food and herbal remedies, shared myths and legends, and ultimately intermarried. Apart from their collective exploitation at the hands of colonial slavery, Africans and Native Americans possessed similar worldviews rooted in their historic relationship to the subtropical coastlands of the middle Atlantic.26 Considering historic circumstances, environmental associations, and sociocultural affiliations, the relationships among African Americans and Native Americans was much more extensive and enduring than most observers acknowledge. The intermarriage of Africans and Native Americans was facilitated by the disproportionate numbers of African male slaves to females (3 to 1) and the decimation of Native American males by disease, enslavement, and prolonged war against the colonists.27

During the intertribal wars encouraged by the English in order to produce slaves, the largest majority of those enslaved were women and children, in accordance with historic patterns of warfare among Native Americans.28 Therefore, the largest numbers of Native American slaves in the early Southeast were women; there were as much as three to five times more Native women than men enslaved.29 Slave owners often desired African men to work the fields paired with Native American women to also work the fields as well as help around the house. John Norris, a South Carolina planter estimated the costs of setting up a plantation:

Imprimis; Fifteen good Negro Men at 45 lb each 675 lb.

Item: Fifteen Indian Women to work in the Field

at 18 lb each, comes to 270 lb.

Item, Three Indian Women as cooks for the Slaves

and other Household Business 55 lb.30Historian J. Leitch Wright suggests that the presence of so many women slaves from the Southeastern Indian nations where matrilineal kinship was the norm helps to explain the prominent role of women in slave culture.31

As Native American societies in the Southeast were primarily matrilineal, African males who married Native American women often became members of the wife’s clan and citizens of the respective nation. As relationships grew, the lines of racial distinction began to blur, and the evolution of red-black people began to pursue its own course. Many of the people known as slaves, free people of color, Africans, or Indians were most often the products of an integrating culture.32 Some aspects of African American culture, including handicrafts, music, and folklore, may be Native American rather than African in origin. The cultures of Africans and Natives intertwined in complex ways in the early Southeast, and material culture, like social organization, often reflected the blending of these two cultures.33

In areas such as Southeastern Virginia, the “Low Country” of the Carolinas, and around Galphintown34 near Savannah, Georgia, communities of Afro-Indians began to arise. The term “mustee” came to distinguish between those who shared African and Native American ancestry from those who were a mixture of European and African. Even after 1720, black and red Carolinians continued to share slave quarters and intimate lives; many wills continued to refer to “all my Slaves, whether Negroes, Indians, Mustees, Or Molattoes.”35 The depth and complexity of this intermixture are revealed in a 1740 slave code in South Carolina that ruled:

…all negroes and Indians, (free Indians in amity with this government, and negroes, mulattoes, and mustezoes, who are now free, excepted) mulattoes or mustezoes who are now, or shall hereafter be in this province, and all their issue and offspring…shall be and they are hereby declared to be, and remain hereafter absolute slaves.36As early as the latter years of the nineteenth century, ethnologists cited the deep relationship between African Americans and Native Americans. James Mooney in 1897 noted: “It is not commonly known that in all southern colonies Indian slaves were bought and sold and kept in servitude and worked in the fields side by side with negroes up to the time of the revolution… Furthermore, as the coast tribes dwindled they were compelled to associate and intermarry with the negroes until they finally lost their identity and were classified with that race, so that a considerable proportion of the blood of the southern negroes is unquestionably Indian.”37 In his 1937 doctoral dissertation, James Hugo Johnston asserted, “The end of Indian slavery came with the final absorption of the blood of the Indian by the more numerous Negro slave. But the blood of the Indian did not become extinct in the slave states, for it continued to flow in the veins of the Negro.”38

Increasingly toward the end of the century, Africans began to flee slavery in larger numbers to settle among the Indians in their immediate vicinity and in so doing became mediums of exchange for non-indigenous culture.39 Therefore, by the time that John Marrant arrived among the Cherokee in the middle of the eighteenth century, there is little doubt that the Cherokee had some prior exposure to both Africans and Christianity. When Marrant was brought before the “King of the Cherokee” that his fate might be determined, he witnessed to the Cherokee in their native tongue:

I cried again, and He was entreated. He said, “Be it as thou wilt;” the Lord appeared most lovely and glorious; the king himself was awakened, and the others set at liberty. A great change took place among the people; the King’s house became God’s house; the soldiers were ordered away; and the poor condemned prisoner had perfect liberty and was treated like a prince. Now the Lord made all my enemies become my great friends.40What Marrant saw as God’s saving grace could have just as easily been a trial by fire or even an elaborate joke upon the naive young missionary. As Michael Roethler puts it in his 1964 dissertation “Negro Slavery among the Cherokee Indians, 1540-1866,” “It is only natural that the Cherokees should judge the value of Christianity by the character of the people who professed it. To them, Christianity was something they might do well to avoid. 41 Therefore, the Cherokees had no reason to suspect the religion of this Negro preacher.” 42

Being thus freed and granted permission to evangelize among the Cherokee, John Marrant did so at great liberty for some nine weeks “dressed much like the king” and becoming fluent in the Cherokee tongue. At the king’s bidding and with fifty Cherokee accompanying him, Marrant thus went forth among a less “savingly wrought upon” people of the Creek Nation where he spent some five weeks. He then traveled for nine weeks among the indigenous peoples of Louisiana so that “the multitudes of hard tongues and of strange speech may learn the language of Canaan, and sing the song of Moses and of the Lamb.”43 Marrant was, as Arthur Schomburg correctly notes, “A Negro in America [like] the Jesuits of old, who spread the seed of Christianity among the American Indians before the birth of the American Republic.”44

. As Marrant was traveling among the Creek Confederation, he may have happened upon another black missionary whose story resembled his own. David George was born of African parents on the plantation in Essex County, Virginia around the year 1742 and attended the “English Church” in Nottoway, Virginia.45 When his owner became too cruel, David George ran away from his plantation and lived among the Creek and Natchez Indians where he became, according to Michel Sobel, a “well-treated chattel servant.” David George eventually left the Creek Nation and settled on the plantation of George Galphin, an Indian Agent for South Carolina (and eventually the Continental Congress), near Silver Bluff, South Carolina. “Galphintown,” as it was called, was throughout the eighteenth century a center for trade between the colonists and the Five Nations of the Southeastern United States; the traffic in both slaves and deer brought large numbers of Africans and Indians to his plantation.46

Galphin, the owner of the settlement, was an gregarious Irishman who had at least four wives including Metawney, the daughter of a Creek headman and at least two Africans, the “Negro Sappho” and the “Negro Mina.”47 The area around the Silver Bluff was a region in the eighteenth century where the three races of colonial America converged. Galphin’s family, itself, revealed the cultural diversity of the area. Members of Galphin’s family were patrons of the Negro Baptist Church at Silver Bluff.48 Jesse (Peters) Galphin was one of the founders of the Silver Bluff Baptist Church and one of the members who helped revive the church following the disastrous effects of the Revolutionary War.49

An interesting associate of George Galphin was the mustee Alexander McGillivray, whose father was Scotch and his mother was Muskogee. Educated in Charleston, he went on to be recognized by George Washington as the head chief of the entire Creek Nation. George Washington would negotiate a treaty with McGillivray in 1790.50 Another prominent traveler in these circles was the enigmatic Tory William Augustus Bowles. Born in Maryland and fleeing British military service to live among the Creek and Seminole, he too was recognized as a leader of the Creek Nation.51 In an interesting note on history, he was also recognized as “duly accredited provincial Grandmaster of the Five Nations” — a title bestowed upon him the Grand Lodge of England.52 In 1790, Bowles and several “Beloved Men” (including the Cherokee GoingSnake and the Creek Tuskeniah, an associate of Tecumseh) traveled to England where they were accepted into the Prince of Wales Lodge #259. Bowles being made a Mason in the Bahamas, he was duly interested in the political affairs of the Caribbean. While he and his native companions were in England, they tried to obtain English assistance for a struggle being led in Santo Domingo by their fellow Freemasons, Jean Jacques Dessalines and Toussaint L’Ouverture.

| “Though a slave and often described as a ‘black pastor’ of the Third African Baptist Church, Henry Francis had no known African ancestry.” | |

When the Revolutionary War threatened the congregation of the isolated Negro Baptist Church in Silver Bluff, Pastor David George and fifty members of the congregation fled to Savannah where the congregation grew and other branches of the church formed. Among the first ministers of the African Baptist Church of Savannah was a former slave by the name of Henry Francis, a minister ordained by Andrew Bryan of the Silver Bluff Baptist Church. Though a slave and often described as a “black pastor” of the Third African Baptist Church, Henry Francis had no known African ancestry.53 Andrew Bryan, pioneer black Baptist, spoke of Henry Francis in a letter to authorities in 1800:

Another dispensation of Providence has much strengthened our hands, and increased our means of information; Henry Francis, lately a slave to the widow of the late Colonel Leroy Hammond, of Augusta, has been purchased by a few humane gentlemen of this place, and liberated to exercise the handsome ministerial gifts he possesses amongst us, and teach our youth to read and write. He is a strong man about forty-nine years of age, whose mother was white and whose father was an Indian. His wife and only son are slaves. Brother Francis has been in the ministry fifteen years, and will soon receive ordination, and will probably become the pastor of a branch of my large church…it will take the rank and title of the 3rd Baptist Church of Savannah.54In 1782 when the British abandoned Savannah, David George fled to Nova Scotia, Canada and lived there until he moved to Sierra Leone in West Africa as part of Granville Sharp’s recolonization movement.55

Most of the early records of the missionaries note that among these mixed peoples of the low country areas, their earliest converts were the enslaved African Americans that lived in Native American communities.56 Among the most successful of the early missions to the South was that of Reverend Samuel Thomas of Goose Creek Parish in South Carolina. Thomas’s twenty black interpreters helped him with his church of nearly one thousand communicants of African and Native American ancestry.57 Records from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in South Carolina repeatedly mention the membership of their early missions and churches as being equally mixed with “negro and indian slaves.” The records also state that the S.P.G. had no qualms about baptizing “the heathen slaves also (Indians and negroes).”58 However, in spite of the S.P.G.’s efforts, many of their owners were resistant to baptizing slaves for fear of their seeing themselves as social equals:

If the masters were but good Christians themselves and would concure with the Ministers, we should have good hopes of the conversion and salvation at least of some of their Negro and Indian slaves. But too many of them rather oppose than concurr with us and are angry with us.59Thus, the earliest churches in the colonial South were mixed congregations of both African American and Native American congregants. As the missionaries made little distinction among “the heathen slave,” those most conversant in the triracial culture became the ministers of the gospel. As African Americans were often “linksters”60 in the Southern frontier, they came to fulfill the role as religious leader of their mixed congregations.

As few missionaries spoke the native languages, the Africans played an intermediary role as teacher, and as of necessity, preacher.61 In addition, many of the earliest black ministers in the missions of the Baptist Churches were former river-cult priests from traditional religions of Africa.62 It is important to note that the river-cult and ritual bathing were important components in traditional Southeastern religion.63 In Southeastern Indian culture, nearly every ritual act, from the celebration of pregnancy to the selection of war leader — from the stomp dance to ball-play, is preceded by “going to water” as a critical part of the religious practice.64 Thus, the previous religious experience of these new Baptist ministers facilitated the acceptance of the Baptist gospel message and ritual practices among Native Americans.

Within the cultural nexus of the integrated community of the early American frontier, a unique synthesis grew in which African and Native American people shared a common religious experience.65 Not only did Africans share with Native Americans, the process of sharing cultural traditions went both ways. From the slave narratives,66 we learn of the role that Native American religious traditions played in African American society:

Dat busk was justa little busk. Dey wasn’t enough men around to have a good one. But I seen lots of big ones. Ones where dey all had de different kinds of “banga.” Dey call all de dances some kind of banga. De chicken dance is de “Tolosabanga”, and de Istifanibanga is de one whar dey make lak dey is skeletons and raw heads coming to git you. De “Hadjobanga” is de crazy dance, and dat is a funny one. Dey all dance crazy and make up funny songs to go wid de dance. Everybody think up funny songs to sing and everybody whoop and laugh all de time.67

When I wuz a boy, dere wuz lotsa Indians livin’ about six miles frum the plantation on which I wuz a slave. De Indians allus held a big dance ever’ few months, an’ all de niggers would try to attend. On one ob dese ostent’tious occasions about 50 of us niggers conceived de idea of goin’, without gettin permits frum de master. As soon as it gets dark, we quietly slips outen de quarters, one by one, so as not to disturb de guards. Arrivin at de dance, we jined in the festivities wid a will. Late dat nite one ob de boys wuz goin down to de spring fo de get a drink ob water when he notice somethin’ movin in de bushes. Gettin up closah, he look’ agin when-lawd hab mersy! Patty rollers!68

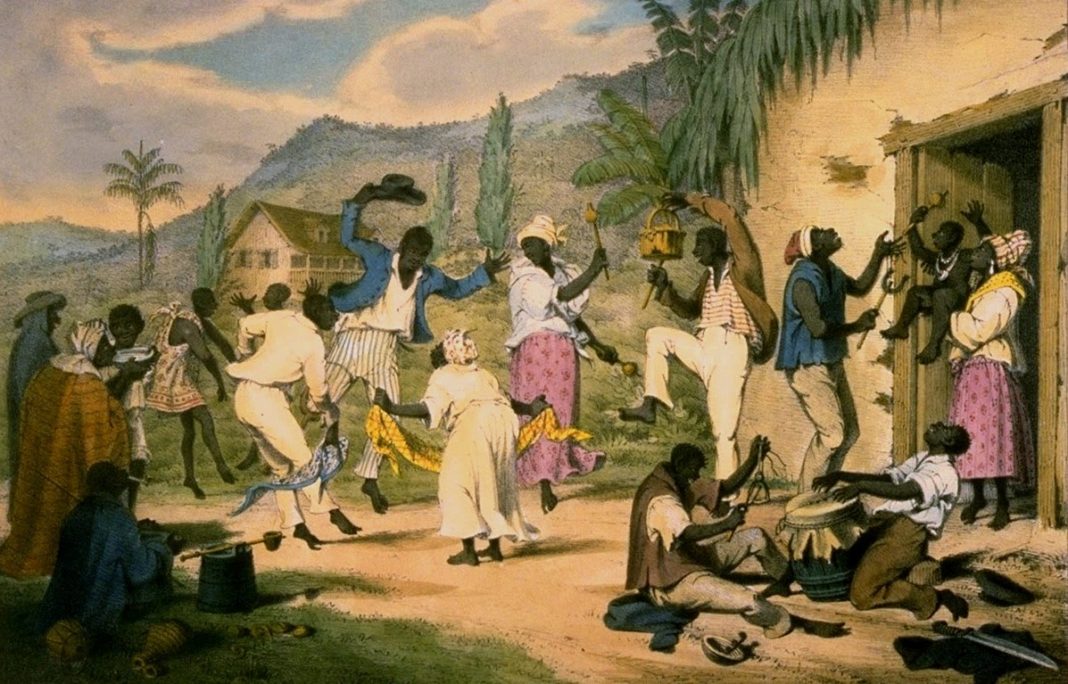

Slaves “mixed and mingled and danced together with the Indians” and the indigenous people of the Southeastern United States welcomed new dances including those from their African counterparts.69 Sacred bonds of blood and metaphysical kinship came to exist between the two peoples and their collective history became an enduring element in American culture.70

Native Americans may have also played a role in the development of African American religion through supporting the “invisible institution” of African American Christianity. The “hush harbors” or brush arbors — hastily constructed “churches” made of a lean-to of tree limbs and branches — that were a significant part of “slave religion” had long been a prominent part of the Southeastern traditional religion. The brush arbor architecture that soon became a critical part of the “camp-meetings” of the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening were directly borrowed from the architecture of the “stomp ground” of Southeastern traditional religious practices. Native Americans often supported the “invisible institution” by offering elements of their own religious practices to the developing “slave religion” as is evidenced by this story of a Cherokee slaveowner, “Master Frank wasn’t no Christian but he would help build brush arbors fer us to have church under and we sho would have big meetings I’ll tell you.”71

Thus, there exists the probability, and if not at least the possibility, that many of those churches historically cited as the earliest “historical Black Baptist churches” were in actuality Aframerindian72 churches. Throughout the Old South, mixed congregations of black and red people worshipped together in ways that were at once both African and Indian. Whether in the “brush arbors” or nascent churches or in the stomp grounds, people recognized the solidarity that only comes in response to an overarching culture of oppression that attempted to define and divide black and red people. By learning to overcome that which separated them as a people, they learned to conquer that “double consciousness” which creates estrangement within themselves. In so doing, they laid the foundation for a common history, one “written in the hearts of our people:”

In truth, sacred bonds between blacks and Native Americans, bonds of blood and metaphysical kinship, cannot be documented solely by factual evidence confirming extensive interaction and intermingling — they are also matters of the heart. These ties are best addressed by those who are not simply concerned with the cold data of history, but who have “history written in the hearts of our people” who then feel for history, not just because it offers facts but because it awakens and sustains connections, renews and nourishes current relations. Before the that is in our hearts can be spoken, remembered with passion and love, we must discuss the myriad ways white supremacy works to impose forgetfulness, creating estrangement between red and black peoples, who though different lived as One.73

In conclusion, Carter G. Woodson observed in 1920 that “one of the longest unwritten chapters of the history of the United States is that treating of the relations of the negroes and the Indians.” 74 In his 1931 work The Story of the Negro, Booker T. Washington observed that, “the association of the negro with the Indian has been so intimate and varied on this continent, and the similarities as well as the differences of their fortunes and characters are so striking that I am tempted to enter at some length into a discussion of their relations of each to the other.”75 In the time since these gifted scholars have written, little has been done by scholars, of all colors and persuasions, to address this important aspect of American history. Our understanding of “slave religion” needs to be framed within the context of the multicultural origins of what we have come to know as the black church; to the extent that we write this story in black and white, we do a disservice to those very peoples whose story we seek to lift up.

It is not the purpose of this paper to detail the specific influences of Native American religious traditions upon the developing black church; to do so is further separate those whom God brought together. What I am proposing is that we take a fresh approach to the early church in the deep South, one that focuses on a more complex understand of the “beloved community.” In taking a serious look at the depth of the interactions, especially the religious interactions, among African American and Native Americans in the Southeastern United States, we may come to reframe our understandings of each, and, ultimately, of ourselves. We come to understand that though this history is seldom told, it is as vibrant, as important, and as “American” as any of our stories.

In case you were wondering what happened to John Marrant, he eventually left the Cherokee and returned to his family but as he was dressed “in the Indian style,” even his family members saw him as “a wild man come out of the woods.” 76 He was later ordained by the Reverend Lemuel Haynes into the Methodist church and eventually moved to Boston where he resettled. There he became friends with another free person of color, Methodist minister, and abolitionist originally from the West Indies by the name of Prince Hall. Prince Hall, and a few of his fellows initiated by an Irish lodge of Freemasons associated with the British Army, founded African Lodge #1 that was eventually recognized by the Grand Lodge of England as African Lodge #459. On June 4, 1789 a report of the Grand Lodge shows that Rev. John Marrant, “the same Rev. Mr. Marrant who achieved fame as a missionary to the Indians,” was admitted and appointed Chaplain of the African Lodge #459.77 On St. John’s Day in 1789, Marrant delivered a speech vilifying the institution of slavery, outlining the African heritage of the Christian religion, and decrying the cynicism of white Freemasons who refuse to recognize the “stile and tile” of black Freemasonry. John Marrant eventually joined his friend David George in Nova Scotia where they struggled for the dignity of their people. Facing great difficulties, eventually Marrant and George set out for Africa and founded the colony of Sierra Leone.

On September 22,1797, a new lodge of Prince Hall Freemasonry was organized in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and received a charter from the Grand Lodge of Prince Hall Freemasonry. The Grand Lodge was now led by now Grandmaster Prince Hall. The Worshipful Master of the Philadelphia Lodge was an Episcopal priest by the name of Absolom Jones and the Treasurer was a friend of his by the name of Richard Allen. Richard Allen and Absolom Jones also went on to attain some status in the African American community, but that is another story.

1 “Wills and Miscellaneous Records,” South Carolina Department of Archives and History, quoted in Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W.W. Norton,1974), 99.

2 John Marrant, A Narrative of the Life of John Marrant, of New York, in North America With [an] account of the conversion of the king of the Cherokees and his daughter (London: C.J. Farncombe, n.d), 5-7.

3 ibid.

4 Carl Waldman, Atlas of the North American Indian (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 72. See also Leo Wiener, Africa and the Discovery of America (Philadelphia, 1920); Jack Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); Ivan Van Sertima, They Came Before Columbus (New York: Random House, 1976); Michael Bradley, Dawn Voyage (Toronto: Summerhill Press, 1987). Jack Forbes, in his work, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples, cites myths from South America detailing a close cooperative relationship between the spirit-powers of Africa and of the Americas. He concludes his discussion of this relationship by stating, `Thus in spiritual as well as secular sense, the American and African peoples have interacted with each other in a variety of settings and situations. These interactions may well have begun in very early times.’

5 It is important to note that there was not an understanding of difference based upon the concept of “race” within Native American cultures as it existed within the European mind. “Race” as an identifying component in interaction did not exist within the traditional nations of the early Americas; even into the nineteenth century the Cherokee were noted for their cultural accommodation. [Tom Hatley, The Dividing Path: Cherokees and South Carolinians through the Revolutionary Era ( New York; Oxford University Press, 1995), 233.] William McLoughlin stressed the importance of clan relationships or larger collective identities (e.g., Ani-Yunwiya, Ani-Tsalagi, Ani-Kituhwagi) within indigenous people as the critical components in their interactions with outsiders; race was not considered a critical element in perception or hostility. [William G. McLoughlin, The Cherokee Ghost Dance: Essays on the Southeastern Indians (Atlanta: Mercer University Press, 1984), 260-265] In her pivotal work, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society 1540-1866, Theda Perdue states that the Cherokee regarded Africans they encountered “simply as other human beings,” and, “since the concept of race did not exist among Indians and since the Cherokees nearly always encountered Africans in the company of Europeans, one supposes that the Cherokee equated the two and failed to distinguish sharply between the races.” [Theda Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society 1540-1866 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979), 36.] Kenneth Wiggins Porter, an historian of African American/Native American relations, concurs with this conclusion: “[we have] no evidence that the northern Indian made any distinction between Negro and white on the basis of skin color, at least, not in the early period and when uninfluenced by white settlers.” [Kenneth W. Porter, Relations Between Negroes and Indians Within the Present United States (Washington, D.C.: The Association for Negro Life and History, 1931), 16.]

6 From the very beginning. the Spaniards were driven by mixed motives, “Civil and sacred interests were intertwined in a system so thorough and so complex as scarcely to be separated, so permanent and pervasive that organic union escapes any but a careful observer.” [W. Eugene Shiels. King and Church:The Rise and Fall of the Patronato Real(Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1961), 9] Central to the Spanish vision of an “increase of temporal prosperity” was a certain human commodity:

Finally, to sum up in a few words the chief results and advantages of our departure and speedy return, I make this promise to our most invincible sovereigns, that, if I am supported by some little assistance from them, I will give them as much gold as they have need of, and, in addition spices, cotton, and mastic, which is found only in chios, and as much aloes-wood, and as many heathen slaves as their majesty may choose to demand… (italics mine)

[Christopher Columbus, “Letter to Gabriel Sanchez” in Old South Leaflets, Volume II, Number 34 (Boston: Directors of the Old South Work, n.d.), 6.]

7 The Requierimento read:If you do so you will do well, and that which you are obliged to do to their highnesses, and we in their name shall receive you in all love and charity, and shall leave you your wives, and your children, and your lands free without servitude, that you may do with them and with yourselves freely that which you like and think best, and they shall not compel you to turn Christians, unless you yourselves, when informed of the truth, should wish to be converted to our holy Catholic faith, as almost all the inhabitants of the rest of the islands have done; and, besides this, their highnesses award you many privileges and exemptions and will grant you many benefits.

But if you do not do this, and maliciously make delay in it, I certify to you that, with the help of God, we shall powerfully enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their highnesses; we shall take you, and your wives, and your children, and shall make slaves of them, and as such shall sell and dispose of them as their highnesses may command; and we shall take away your goods, and shall do you all the mischief and damage that we can, as to vassals who do not obey, and refuse to receive their lord, and resist and contradict him; and we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault, and not that of their highnesses, or ours, nor of these cavaliers who come with us. And that we have said this to you, and made this Requisition, we request the notary here present to give us this testimony in writing, and we ask the rest who are present that they should be witnesses of this Requisition

[ “El Requerimiento” in Wilcomb Washburn, ed. The Indian and the White Man (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books,1964) pp. 307-308]

8 Edward Gaylord Bourne, Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto, 2 Vols. (New York, 1922), 60, 94-9, 103-105. Ponce de Leon’s 1512 patent from the Spanish authorities provided that any Indians that he might discover in the Americas should be divided among the members of his expedition that they should “derive whatever advantage might be secured thereby.” LucasVasquez de Ayllon’s 1523 cedula authorized him to “purchase prisoners of war held as slaves held by the natives, to employ them on his farms and export them as he saw fit, without the payment of any duty whatsoever upon them.” [Woodbury Lowery, The Spanish Settlements within the Present Limits of the United States: 1513-1561, (New York: Bolton and Ross, 1905), 162-169].

9 J.B. Davis, “Indian Territory in 1878,” Chronicles of Oklahoma IV (1926): 264.

10 See Almon Lauber, Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1933); Barbara Olexer, The Enslavement of the American Indian (Monroe, N.Y.: Library Research Associates, 1982); J. Leitch Wright, The Only Land They Knew:The Tragic Story of the American Indian in the Old South (New York: Free Press, 1981); Jack Weatherford, Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America (New York: Crown Publishers, 1991); Patrick Minges, Evangelism and Enslavement: Catholic and Protestant Missions to the Native Americans (Unpublished Manuscript, 1992).

11 James Wilson, The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1998), 63-64; Audrey Smedley, Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993), 56-61); Edmund S. Morgan. American Slavery-American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia.(New York: Norton and Co., 1975), 20; Francis Jennings, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,1975), 46; Ronald Sanders. Lost Tribes and Promised Lands: The Origins of American Racism. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1978), 228.

12 Booker T. Washington, The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery Vol. 1 (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1909), 128-130. See also Almon Lauber, Indian Slavery in Colonial Times within the Present Limits of the United States (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1933); Barbara Olexer, The Enslavement of the American Indian (Monroe, N.Y.: Library Research Associates, 1982); J. Leitch Wright, The Only Land They Knew:The Tragic Story of the American Indian in the Old South (New York: Free Press, 1981); Jack Weatherford, Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America (New York: Crown Publishers, 1991); Patrick Minges, Evangelism and Enslavement: Catholic and Protestant Missions to the Native Americans (Unpublished Manuscript, 1992).

13 Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W. W. Norton Company, 1974), 39.

14 Lauber, 39.

15 Washington, 129.

16 Gary Nash, Red,White and Black: The Peoples of Early America (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1974), 130.

17 Tom Hatley, The Dividing Path: Cherokees and South Carolinians through the Revolutionary Era ( New York; Oxford University Press, 1995), 33.

18 H.T. Malone, Cherokees of the Old South: A People in Transition (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1956), 20.

19 James Mooney, “Myths of the Cherokees” (Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900), 32.

20 Ibid.

21 Interestingly enough, these twenty Africans brought into the United States were part of a plan by Virginian, Sir Edwin Sandys to finance a fledgling school for Indians named William and Mary. Whenever Native American children in the Carolinas and Virginia were seized as captives of war, they were sent to William and Mary. The irony that African slaves were first brought to the United States by the English to finance a school for Indian slaves is quite striking indeed. [Barbara Olexer, The Enslavement of the American Indian (Monroe, N.Y.: Library Research Associates, 1982), 89.]

22 Indian slaves were considered to be “sullen, insubordinate, and short lived,” A.B. Hart quoted in Sanford Wilson, “Indian Slavery in the South Carolina Region,” Journal of Negro History 22 (1935), 440. The article further describes Native American slaves as “not of such robust and strong bodies, as to lift great burdens, and endure labor and slavish work.” Native Americans were not without some commercial value. They were often seized throughout the South and taken to the slave markets and traded at an exchange rate of two for one for African Americans. An interesting spin on the story comes from Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois who, even in agreement with the positions stated above, stated that “The Indian refused to submit to bondage and to learn the white man’s ways. The result is that the greater portion of the American Indians have disappeared, the greater portion of those who remain are not civilized. The Negro, wiser and more enduring than the Indian, patiently endured slavery; and contact with the white man has given him a civilization vastly superior to that of the Indian.” (Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, The Negro in the South: His Economic Progress in Relation to His Moral and Religious Development (Philadelphia, George W. Jacobs and Company, 1907) 14.) Washington reiterates this point by quoting Dr. John Spencer, who in discussing the collapse of indentured servitude and Indian slavery, stated “In each case it was survival of the fittest. Both Indian slavery and white servitude were to go down before the black man’s superior endurance, docility, and labour capacity.” (Dr. John Spencer quoted in Booker T. Washington, The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery Vol. 1 (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1909) 113).

23 George Washington Williams, History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers, and as Citizens (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1882), 123-180.

24 David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1966), 176.

25 Booker T. Washington in The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery describes it thus: “During all this time, for a hundred years or maybe more, the Indian and the Negro worked side by side as slaves. In all the laws and regulations of the Colonial days, the same rule which applied to the Indian was also applied to the Negro slaves…In all other regulations that were made in the earlier days for the control of the slaves, mention is invariably made of the Indian as well as the Negro.” (130).

26 William Willis, “Anthropology and Negroes on the Southern Colonial Frontier,” in James Curtis and Lewis Gould, eds., The Black Experience in America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1970), 47-48.

27 J. Leitch Wright, The Only Land They Knew: The Tragic Story of the American Indian in the Old South (New York: Free Press, 1981), 258.

28 Wood, 39; Theda Perdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700-1835 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 68.

29 Perdue, Cherokee Women, 68.

30 John Norris, quoted in Verner Crane, The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732 (Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press, 1928), 113.

31 Wright, The Only Land They Knew, 148-150, 248-278.

32 Melville Herskovits, The American Negro: A Study in Crossing (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), 3-15; For excellent surveys and discussions of this phenomenon, see: Kenneth W. Porter, Relations Between Negroes and Indians Within the Present United State (Washington, D.C.: The Association for Negro Life and History, 1931); J.Leitch Wright, The Only Land They Knew:The Tragic Story of the American Indian in the Old South (New York: Free Press, 1981); Jack Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples (Urbana:University of Illinois Press,1993); Laurence Foster, Negro-Indian Relations in the Southeast (Philadelphia, n.p. 1935); Booker T. Washington, The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery Vol 1. (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1909), 125-143. Washington notes as prominent African American/ native American mixed-blood Frederick Douglas, Paul Cuffee, and Crispus Attucks (132).

33 Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archeology and Early African America, 1650-1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Instituion Press, 1992)

34 Galphintown was named for George Galphin, a n Irishman who was a prominent Indian trader in the Creek Nation and Indian Agent for the First Continental Congress.Galphin extensively utilized African Americans as scouts, translators and laborers in his trade with the Five Nations of the Southeastern United States. Galphin at one point or another in his life had a number of African American and Native American wives and a number of his children were of mixed blood. For further information, see J. Leitch Wright, Creeks and Seminoles (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986); James Melvin Washington, Frustrated Fellowship, the Black Baptist Quest for Social Power (Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1986); Joel W. Martin, Sacred Revolt : the Muskogees’ Struggle for a New World (Boston : Beacon Press, 1991); Angie Debo, The Road to Disapearance (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941);William R. Denslow, Freemasonry and the American Indian (St Louis: Missouri Lodge of Research, 1956).

35 “Wills and Miscellaneous Records,” South Carolina Department of Archives and History, quoted in Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W.W. Norton,1974), 99.

36 John Curdman Hurd, The Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United States (Boston, 1858-1862, Vol. 1), 303.

37 James Mooney, “Myths of the Cherokees” (Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900), 233.

38 James Hugo Johnston, Race Relations in Virginia and Miscegenation in the South 1776-1860 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1970), 171-2.

39 From the earliest periods of the institution of slavery and well into the nineteenth century, African slaves had been fleeing slavery and repression along the same routes that their native forebears had used in earlier times.[Wood, 260-261] As historian and Member of Congress Joshua Giddings described it a hundred years later, it was rite of passage:

The efforts of the Carolinians to enslave the Indians, brought with them the natural and appropriate penalties. The Indians began to make their escape from slavery to the Indian Country. Their example was soon followed by the African Slaves, who also fled to the Indian Country, and, in order to secure themselves from pursuit continued their journey. [Joshua Giddings, The exiles of Florida: or, The crimes committed by our government against the Maroons, who fled from South Carolina and other slave states, seeking protection under Spanish laws (Columbus, Ohio: Follett, Foster and Company, 1858)]As a result of intermarriage between Africans and Indians during their collective enslavement, many Native American escapees would return to their former plantations to free their spouses and children still held in captivity. As Michael Roethler puts it in his essay Negro Slavery Among the Cherokee Indians 1540-1866, the Cherokee considered it “just retribution” that they who had been enslaved helped those enslaved to flee their persecutors in the Carolinas.[ Michael Roethler, “Negro Slavery among the Cherokee Indians, 1540-1866” (Ph.D. Dissertation.,Fordham Univ.,1964), 36-40]

40 Marrant, 18.

41 Chief Yonaguska, after listening to a portion of the Gospel according to St. Matthew, replied sharply, “Well, it seems to be a good book, but it is strange that the white people are not better after having it so long.” (Robert Walker, Torchlights to the Cherokees, (New York: MacMillan Company, 1931), 15-16.

42 Michael Roethler, “Negro Slavery among the Cherokee Indians, 1540-1866” (Ph.D. Dissertation.,Fordham Univ.,1964), 126.

43 Marrant, 24.

44 Arthur Schomburg, “Two Negro Missionaries to the American Indians, John Marrant and John Stewart” The Journal of Negro History 21 (No. 1, January, 1936): 400.

45 Among the Native Americans of Southeastern Virginia from whence David George fled, there was a very strong Aframerindian community. Thomas Jefferson noted that among the Mattaponies, there was “more negro than Indian blood in them.” The Gingaskin, Nottoway, and Pamunkeys were often asserted to be more Black than Indian. [Porter, Relations, 314]. In a later period, many of the Powhatans were suspected of being in league with Nat Turner and supporting his runaways following the insurrection of 1831. Many of the Powhatan Indians served the Union forces of the Civil War during guerilla activities in Southeastern Virginia. [Lawrence Hauptmann, Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War (New York: Free Press, 1995), 66-73].

46 Edward Freeman, The Epoch of Negro Baptists and The Foreign Missions Boards [ National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc] (Kansas City: The National Seminary Press, 1953), 29.

47 J. Leitch Wright, Creeks and Seminoles (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 81; Kathryn E. Holland Braund, Deerskins and Duffels: Creek-Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685-1815 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 46.

48 Wright, Creeks and Seminoles, 81.

49 Freeman, 30-33.

50 Alender McGillivray was also a Freemason as was George Washington. Many of the traditional leaders of the Native Americans were Freemasons. Tecumseh, a Shawnee prophet who reportedly “was made a Mason while on a visit to Philadelphia,” was the leader of a Pan-Indian movement to resist white encroachment in the late eighteenth century. Alexander McGillivray, a mixed blood leader of the Muskogee, and Joseph Brant, a mixed blood leader of the Mohawk, were skilled political leaders who set European colonists against one another in order to protect and preserve traditional interests in early America. Brant was reportedly America’s first Native American Freemason when he was raised by an English Grand Lodge (much the same as Prince Hall); McGillivray’s lodge membership was not know but he was buried with a Masonic funeral. Red Jacket, famous orator of the Seneca and leader of the traditionalist resistance among the Iroquois, was a Freemason who reportedly encouraged the Seneca to reject William Morgan when he sought refuge among them. Red Jacket’s grandnephew, General Ely S. Parker, was General U.S. Grant’s Adjutant and drew up the conditions of surrender at Appomatox. Robert E. Lee, thinking Parker was an African-American , refused to meet with Grant until the matter was cleared up. William Augustus Bowles, leader of a Creek/Seminole/African-American resistance movement in Florida, was also a Freemason having been raised in the Bahamas. Pushmataha, a Choctaw leader who encouraged friendship with the whites and resisted Tecumseh, was also a Freemason. (William R Denslow, Freemasonry and the American Indian (St Louis: Missouri Lodge of Research, 1956).

51 William Augustus Bowles is one of the most interesting characters in American history. He was born in Maryland in 1763 and joined the British forces at the age of thirteen. When he was fifteen, he fled the British Army and went to live among the African/Creek/Seminole people of Southern Florida. He became the war leader of a five nation confederacy entitled “the nation of Muscogee” and engaged in military struggles against the Floridians. Fleeing pursuit once again, he fled to the Bahamas in 1786 where he sought initiation into the Freemasonic order for a second time (the first time was in Philadelphia in 1783); this time he was admitted. When he and his friends from the Creek and Cherokee Nation entered Prince of Wales Lodge #259, he was introduced as “a Chief of the Creek Nation, whose love of Masonry has induced him to wish it may be introduced into the interior part of America, whereby the cause of humanity and brotherly love will go hand in hand with the native courage of the Indians, and by the union lead them on to the highest title that can be conferred on man.” In 1795, the records of the Grand Lodge of England showed Bowles as the duly accredited provincial Grandmaster of the Five Nations. In 1799, Bowles returned to the United States and tried to finance a revolution in order to set up a free and independent Muscogee State along the frontier of the colonial United States; in so doing Bowles freely associated with Indians and their African cohorts of the Seminole Nation. (Cotterill, 127-130) J. Leitch Wright credits Bowles with having spread the abolitionist message among the Upper Creek and Chickamaguan Cherokee in the eighteenth century through the use of black interpreters. Both Chief Bowlegs of the Seminole Nation and Chief Bowl of the Cherokee Nation are supposed descendants of William Augustus Bowles. (Wright, Creeks and Seminoles, 58 ff).

52 Denslow, 127-129.

53 Wright, Creeks and Seminoles, 81.

54 Letter of Andrew Bryan to Reverend Doctor Rippon in Milton Sernett, ed., Afro-American Religious History: A Documentary Witness (Durham: Duke University Press, 1985), 49.

55 Edward Freeman, The Epoch of Negro Baptists and The Foreign Missions Boards [ National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc] (Kansas City: The National Seminary Press, 1953), 27.

56 Willam G. McLoughlin, Cherokees and Missionaries, 1789-1839 (Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 48; Perdue, 89; William Gerald McLoughlin, Champions of the Cherokees: Evan and John B. Jones (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990), 21; Wright, Creeks and Seminoles, 223; Eighth Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Boston,1818), 16; Ninth Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Boston,1819), 19. Among the first missionaries to the Cherokee were the Moravians Abraham Steiner and Frederick C. De Schweinitz. The mission to the Cherokee was not successful because the Moravians could not speak Cherokee and attracted largely the black members of the Cherokee Nation who were bilingual. However, because the Moravians did not consider the Africans to be worthy of church admission; they offered them “special seats” at communion and gave them the cup “last of all.” In ignoring the historic cultural relationship between the Africans and the Cherokees, the missionaries tossed away their greatest opportunity for transmitting their message to a larger Cherokee audience and doomed their missions to failure.

57 Edward Freeman, The Epoch of Negro Baptists and The Foreign Missions Boards [ National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc] (Kansas City: The National Seminary Press, 1953), 10.

58 Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, Classified Digest of the Records of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts 1701-1892 (London: Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, 1893), 12.

59 Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, 16-17.

60 “linkster” is a term from Southern culture which denotes a person who serves to facilitate relationships among peoples of different cultures. Quite often, these linksters were scouts, surveyors, and tradesmen who interacted on the colonial frontier.

61 The positive attitude of the Cherokees toward African-American missionaries could be related to the fact that the first missionary among the Cherokee was the black Methodist, John Marrant.

62 Melville Herskovitz, “Social History of the Negro,” A Handbook of Social Psychology (Worcester, J. Clark Press, 1935), 256.

63 James Mooney, “The Cherokee River Cult” in The Journal of American Folklore 13: 48 (January-March 1900)

64 Charles Hudson, The Southeastern Indians (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976), 321 ff.

65 J.Leitch Wright. The Only Land They Knew:The Tragic Story of the American Indian in the Old South (New York:Free Press, 1981), 248-290.

66 A recently-released work The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1996) edited by Lindsey Baker and Julie Baker provides us with an excellent access to these materials with respect to Oklahoma. The same can be said about George Rawick’s The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport CT.: 1972); it provides us with an easily accessible resource. However, the best source is still the microform edition of the Federal Writers’ Project’s Slave Narratives: a Folk History of Slavery in the United States, from Interviews with Former Slaves (Washington : Library of Congress Project, 1941). With respect to the a collection of narratives from the Indian Territory, the Indian-Pioneer History Project, edited by Grant Foreman, we can look forward to the day when someone provides a more accessible version of this quite unwieldy project. The wealth of information here is invaluable; the work itself is quite difficult. For essays on the problems and pleasures of using the slave narratives, see John Blassingame, “Using the testimony of Ex-Slaves: Approaches and Problems” in Journal of Southern History 41: (November, 1975): 473-92; C. Vann Woodward, “History from Slave Sources” in American Historical Review 79 (April 1974): 470-81; B.A. Botkin, “The Slave as His Own Interpreter” in Library of Congress Quarterly Journal of Current Acquisitions 2 (July/September 1944): 37-63.

67 Lucinda Davis in Works Progress Administration: Oklahoma Writers Project, Slave Narratives (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932) 58

68 Preston Kyles in Works Progress Administration: Arkansas Writers Project, Slave Narratives (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932) 220.

69 J. Leitch Wright, Creeks and Seminoles, 95

70 bell hooks, “Revolutionary Renegades: Native Americans, African Americans, and Black Indians” Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press, 1992), 183.

71 Kiziah Love in Works Progress Administration: Oklahoma Writers Project, Slave Narratives (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932), 196.

72 “Thus we observe that relations between Negroes and Indians have been of significance historically, through influencing on occasion the Indian relations of the United States government, and to a much larger extent biologically, through modifying the racial make-up of both the races and even, as some believe, creating a new race which might, perhaps, for want of better term, be called “Aframerindian.” Kenneth Wiggins Porter, “Notes Supplementary to `Relations between Negroes and Indians’ ” in The Journal of Negro History XVIII (January, 1933, Number 1): 321.

73 bell hooks, “Revolutionary Renegades: Native Americans, African Americans, and Black Indians” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press, 1992), 183.

74 Carter G. Woodson, “The Relations of Negroes and Indians in Massachusetts,” Journal of Negro History 5 (1920): 45.

75 Booker T. Washington, The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery Vol. 1 (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1909), 126.

76 Marrant, 21.

77 Harry E. Davis, “Doucuments relating to Negro Masonry” in The Journal of Negro History 21: (No. 1, Jamuary 1936), 422-423.